SITE Santa Fe

August 3, 2018 – January 6, 2019

Everyone has a biennial these days—a sprawling exhibition that brings in outside curators to cultivate a conversation among a bunch of artists that speaks to the global art community—but who is the biennial for? At SITElines.2018: Casa tomada, the loose thread is again the art of the Americas, read through the lens of Julio Cortázar’s short story in which siblings are gradually pushed out of their ancestral home by unseen forces. The show includes twenty-three artists from eight countries, and while the installation and dearth of wall text makes connecting the works to one another a challenge, the exhibition entrances with its heavy emphasis on emerging and early-career artists, ten of whom created new works for the show.

With Andrea Fraser’s pie charts of sources of major contemporary art museum funding plastered on the exterior wall of the show, Casa tomada immediately and refreshingly becomes a critique of the museum in which it is housed. The curators’ themes of belonging and access are most legible in the context of her book, 2016 in Museums, Money, and Politics, which documents the political leanings of contemporary art museum boards and funders. Right away, the viewer is asked, “Who is the contemporary art museum for? Who funds it and why?” If the symbolic house of the exhibition’s title is the museum, or a particular art world, (or Bard’s curatorial studies program, from which all three curators graduated), perhaps the viewer of this show is being pushed out: by conservative boards, by conservative backers, by an as-yet-undetermined role for contemporary biennials in relation to the average museum-goer. (These questions circled back to me at the end of the show, where I noticed Laura Bush taking a tour.)

The works that succeeded at bringing me in to the house were those that served a documentary function, like Venezuelan artists Ángela Bonadies and Juan José Olavarría’s La Torre de David, a series of photos of squatters in an unfinished skyscraper in Caracas. The signs of home life in a typically commercial space are both uncanny and not so unexpected as a representation of late capitalism: the huge budget bank building never completed, the swaths of homeless people ready to fill any unused space. The photos, unlike most of the work in the show, are accompanied by a brief label explaining some context. Many of the pieces in Casa tomada appear without any additional wall text or commentary beyond the artist’s name, home city, and materials. How many visitors to SITE will approach one of Mexican artist Tania Pérez Córdova’s sculptures, which I first saw in her solo show at MCA Chicago, then retreat to the labels on the wall, read the list of materials, then return to the work to get a better look at the objects—jewelry, money, trash—embedded within them? How many will walk by without knowing anything about the work or bothering to look closely at pieces whose visual impact lies in their subtlety?

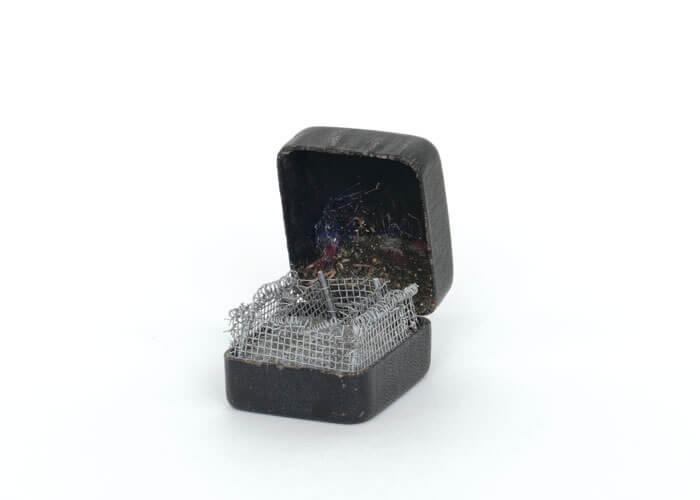

The flashiest room of Casa tomada is the last one, a giant space clustered with brightly painted Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun sculptures, a series of Edgar Heap of Birds’s textual prints titled Surviving Active Shooter Custer, and a glass greenhouse-type structure filled with Canadian-Trinidadian artist Curtis Talwst Santiago’s jewelry box dioramas. Depicting scenes of police brutality, art history, sexual encounters, and natural disasters, Santiago’s Infinity Series builds forty miniature houses within a glass house within Casa tomada, the house overtaken.

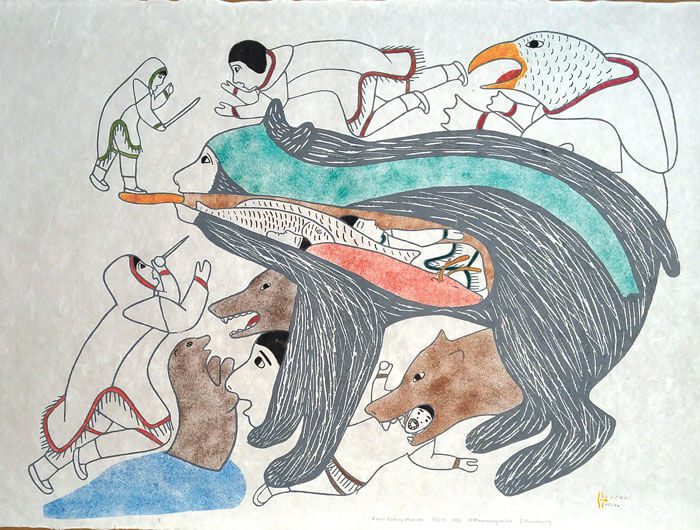

However, the room where I felt most at home, most welcomed by our curatorial hosts, was a rear corner gallery that often feels forgotten when SITE installs a large-scale show (the only kind they’ve had in their main space since their renovation). New Mexican artist Eric-Paul Riege’s regalia hang in a hooghan, a nest of eight looms meant to symbolize Na’ashjé’íí Asdzáá, the home of the spiderwoman who taught Navajo people to weave. A series of colorful, fantastical drawings and embroidered felt hangings by beloved Inuit artist Victoria Mamnguqsualuk keep Riege’s new installation company, though her drawings have been installed in awkwardly anthropological cases (and her other two drawings are hung for some reason in the other room, on the other side of the wall). In this room, I felt a sense of intimacy, of welcome, and for once I was close enough to the works not to feel physically at sea in the gargantuan space. Texture and humor abound in these works. What seem like traditional regalia weighed down by history are undercut by Riege’s inclusion of what appears to be a Beanie Baby sheep’s head on the back of one piece, a pair of stuffed animal legs dangling from the other. Visitors are invited to touch Riege’s works. “Being in a critique-heavy place like a contemporary art museum,” he says, “I want there to be a warmth to it and a softness that allows people to want to access through touch.”

6 x 4 x 4 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist and Rachel Uffner Gallery.