New Mexico artist Santiago Perez’s work is steeped in myth, folk tales, art history, anthropology, TV cartoons, and satire, aimed at the human condition.

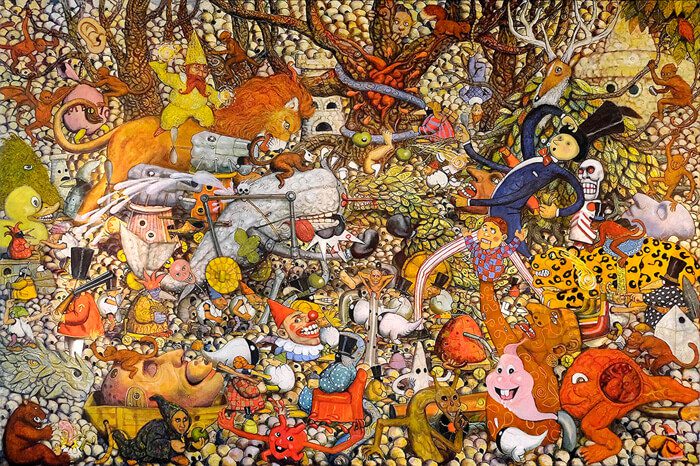

I first saw a painting by the artist Santiago Perez at the South Broadway Cultural Center in Albuquerque some ten years ago. There was a large lion in the middle, and fantastic figures all around. They seemed vaguely familiar, as in a dream. I was delighted by the mischievous figures and the bright colors. It was a simple feeling, yet Perez’s work is not simple. Steeped in myth, folk tales, art history, anthropology, TV cartoons, and satire, the paintings are aimed at the human condition. His work has a magical, fairy-tale quality, like a child’s picture book, but he is not illustrating someone else’s text, but his own fantastical and sardonic material.

I have seen Perez’s work at the Albuquerque Museum of Art and Art History, at the Hispanic Cultural Center, and most recently at 516 Arts, where I saw his small constructed house, painted inside and out with glowing scenes. In order to enter the little house, and see its dimly lit interior, the viewer must crawl through the meter-high door on their hands and knees. When I came out again, I saw a tall gentleman in an expensive suit examining the piece. I told him, “There are different scenes painted on the inside, but you have to crawl in.” The man in the grey suit took off his highly polished shoes, placed them neatly to one side, and crawled into the little house. Unless you be like a little child, said Jesus, you cannot enter the kingdom of heaven.

Santiago Perez was born in Texas and grew up in the country. After a stint as a schoolteacher, he joined the Air Force where he spent twenty-four years. He became a full-time artist after retiring. A prolific artist, he is represented by Nüart Gallery in Santa Fe and by Sandy Carson Gallery in Denver. In addition to his surreal paintings, he also makes paintings of cowboys and horses in a looser impasto style.

Perez spoke to me by phone from his house near Tijeras, in the Manzano Mountains, on March 12, 2021. He speaks in a genial, unpretentious manner about his life, the artists that influenced him, and the ideas that go into his work. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Krittika Ramanujan: How was the COVID vaccine?

Santiago Perez: It was fine. My arm is a little sore.

I first saw your work at the South Broadway Cultural Center and then at the Albuquerque Museum. You had a small house painted inside and out, and you had to enter by crawling inside.

Yes, I guess it’s a little interactive, an immersive painting. Actually the Fantastical House was painted twice inside. I painted it and I didn’t like it, or I thought it was ok, but then I repainted it for 516 Arts. I took a swipe—a gentle swipe—at the former president. I was trying to make it more cartoon-like, more Beavis and Butthead. The off-the-wall stuff I do requires heavy materials, an assistant or two, and takes up space. It gives [people] another experience.

So, you were born in San Antonio, Texas?

Yes, in 1950. But, we didn’t live there, we lived in small towns around it. My father was an itinerant worker, working on people’s farms, taking care of cows, horses, goats, whatever animals they had. My mother, as a girl, worked with her large family picking/harvesting seasonal crops all over the U.S. We would live on these places, they had houses for the workers, which varied from very bad to livable [laughs]. It was rural, agrarian, you could say. It was a lot of fun, running through the woods. My two parents, however, emphasized education and two of us kids went to college.

How did you become interested in art?

I don’t know exactly. My uncle was a graphic designer and he was a model [for me]. My older brothers were always drawing, I tried to keep up with them. I spent hours on it. It was… sibling rivalry? We drew horses, cowboys, animals familiar to us in the woods, cartoons on TV. I appreciated the inventiveness in the cartoons.

Belief systems are swirling all around us, crashing into each other and causing chaos and confusion.

Then, you went into the army for twenty-four years. How did that happen?

After college, I was a teacher for two years. I went into the Air Force, it was the easiest to get into [laughs].

Weirdly, I know a number of artists who came from the Air Force.

I was an administrative clerk, and then I went into computer programming. They send you to various schools to get trained. I went to Mississippi. The base was in Biloxi, on the coast. I thought Texas was humid, but Biloxi!

Did you paint while in the Air Force?

Yes, I wouldn’t give up my… I don’t know if I’d call them my studies. I would practice my drawing and painting, I’d do a little after my work, weekends. I was attracted to primarily Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s, also Pop Realism. I didn’t see them first hand, I got it through books.

I was getting enthused about being an artist. I wondered, “how do you make a living at that?”

In Germany, I was a part of small live drawing groups, small groups that would exhibit together, we had our own booth at a painting fair. When I came back to the U.S., to Colorado Springs, I met other artists. I did plein air landscapes, the landscape there was beautiful. I got into exhibitions. Sandy Carson, the director of a Denver gallery, came by my studio and invited me to join [her gallery]. She helped me a lot.

You mention Bosch and a lot of early Renaissance artists and I can see that influence in your paintings.

I was stationed in West Berlin, and there they had some world-famous museums and collections, [I saw] for the first time in person many artists I had seen only in books, they had the Northern European Artists, Rembrandt, Ruysdael, Caravaggio, Brueghel, Van der Wyden, and the Dutch painters, landscape painters. I learned from the art, and books. Since then I’ve become quite a biography reader, reading about the times, the limitations they had, how they overcame them to produce their art, the culture. I use reading to bolster the art.

Also, Michelangelo was a big influence, mostly his drawings. He had this technique, called the serpentine or sinuous line.

Where it’s just one line, you don’t lift your hand from the paper?

Yes. I did a few Michelangelo drawings. I did some copies. Copying is a tool for all artists that they used to use [in learning technique]. From there my drawing became more expressionistic than naturalistic.

They also had a lot of Mexican, Toltec heads in Berlin. A huge mass of stone.

The world in your paintings—do you feel as if it existed before, and you’re discovering that landscape, or do you feel it’s developing as you’re painting it? Like Tolkien, for instance, he had thought about his work for a long time before he wrote it down.

I started when I was forty, before that I was preparing, though I didn’t know what I was preparing for.

I had it in the back of my mind, keeping all the imagery in storage, I wouldn’t say in my unconscious. Look at Bosch, look at Brueghel, they had cartoon characters, almost like the TV in those days, fantastic imagery, they could put in all these inventions about Christian imagery, create demons, odd creatures. They came from heavily controlled societies, where kings, landowners, and the church in the feudal period, all these powerful institutions controlled [their lives].

Do you think we’re in a feudal society now?

Off of a pandemic, our society—with the help of social media and political leaders—has turned into a whirl of conspiracies, fears, and phobias. All have come out in an atavistic way. We are still quite medieval; scratch the modernity away, and it’s there underneath.

The rational worldview has its own fallacies, believing only in the material, logical, and scientific, what is provable—creating artwork, especially what I do, belies this. Belief systems are swirling all around us, crashing into each other and causing chaos and confusion.

How did you get into doing more fantastical paintings? A lot of your work is very intricate.

I began doing more angsty, expressionistic figures. I looked at artists like Max Beckmann. I looked at the Neo-expressionists—Sandro Cooke, Francesco Clemente, Anselm Kiefer—and they were a big influence to get more wild, to have more impact, to get more emotional in my painting. I always get in the tail-end of movements, because that’s when they come out in books [laughs].

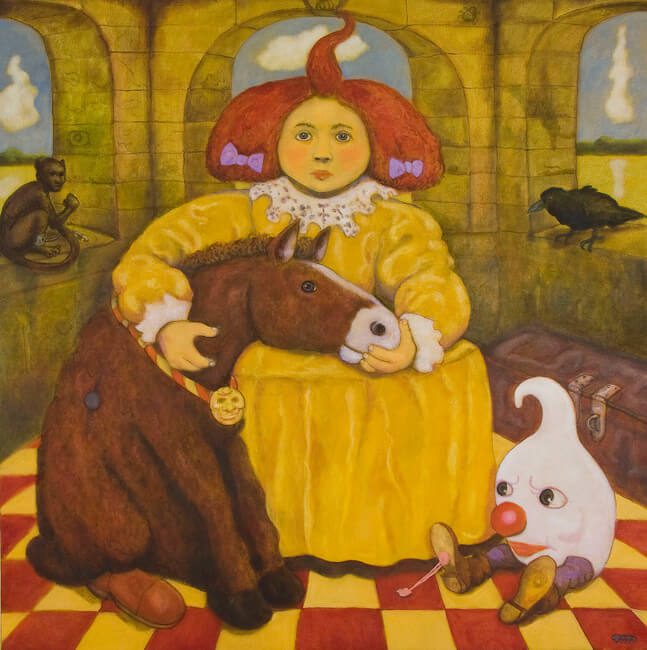

I also [still] liked cartoons, I combined painting animals, borrowing and stealing from other artists [laughs ironically], and going for humor. I created a pictorial vocabulary that I used and repeated in lots of paintings, such as The Little Boy on White Horse and The Little Boy on a Lion; a bird-like creature of the Plague years I called a Mergatroid; and the Eggmen, little men with bodies encased in eggshells.

I throw in fairy tales, folk tales from many cultures. I try to keep it painterly.

First [I go] for characters—a little baby on a giant horse. I like what I’m doing in my painting, I’m getting more expressive. I use European and English royalty: The Queen Mother, Mother Earth, Queen Goddess. This imagery evolved in my mind, imagination connecting to ideas of the archetypes. My paintings were a bridge to a magical universe, where reason is sometimes suspended and mythical beings exist.

We, our society, the world, live in a fish bowl. In pre-Columbian Mexico, there was no alternative to being an Aztec unless you went out and met some other tribe. Of course, then they met the Spanish tribe. They’re living in a magical civilization, their gods were appropriate to their civilization. Pretty much the same in Western culture, we have our “gods” that ask for our sacrifice, our obedience: money, political parties, religious beliefs, individualism, freedom.

Through painting I have tried to come to a basic understanding of humanity.

What is the process of making a painting like for you? Do you start by sketching a character out, do you do a blueprint for the whole composition, does it come to you as you go along?

All of the above. I’m inspired by titles, which evoke a visual counterpart. I take titles from pop songs, and a visual image comes to you immediately. [Like] King Crimson, The Return of the Crimson Kings, which lent itself to an ambience of medieval imagery.

The actual process I want to finish as quickly as possible. I’ll do four or five passes through it. I’ll start with a central figure, things revolve around them. Sometimes I do them in two weeks, working a few hours a day. Sometimes they stick around for a few years, because I don’t know how to finish them. I’m geared for the finished painting. I’m not a process guy, I’m an inspiration guy.

In making them, if I am amazed, then maybe the viewer will be, also. I want the impact of a large painting to interest you… for a few seconds, which is usually what people spend looking at them.

What does being an artist mean to you now?

Painting helps my confused state of mind. [Laughs] I ask myself, why continue to paint? Even Gerhard Richter couldn’t answer that. He said, “Painting can still do something,” and I believe that. What it can do is make an individual grow in ways he didn’t expect. It makes your life seem important.

The illusion that art can do something to change the world is a great idea, but it can be self-delusion. This idea has come to mean more to me after I read Viktor Shklovsky’s Energy of Delusion. The artist, or anyone for that matter, bases his future life and work on the imaginary ghosts of his mind.

It is easy to arrive at nihilism. Sometimes I’m disgusted, and I stop. Then a few hours, days, weeks later I’m back at it again.