At the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, worldwide Indigenous artists render the effects of uranium mining and nuclear bomb testing on their lands and people.

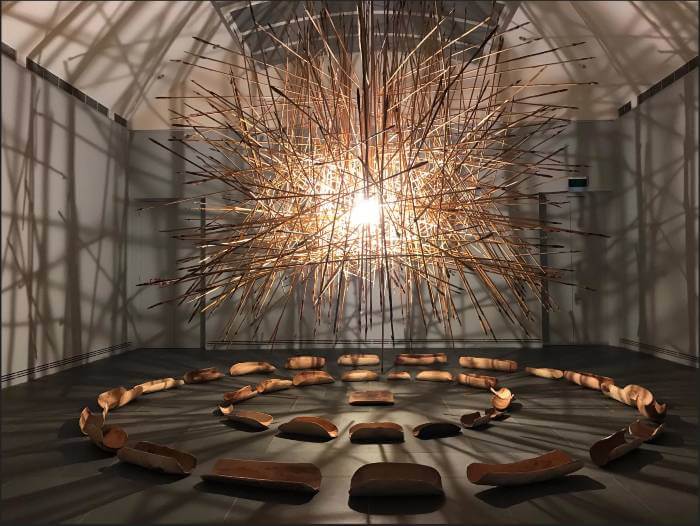

550 suspended kulata (spears), twenty-seven coolamons, dimensions variable. Courtesy IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology

August 20, 2021-July 10, 2022

IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts, Santa Fe

In modern Western art, the individual’s self-expression and the political are sometimes in opposition to one another. In Exposure: Native Art and Political Ecology at IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, this is not the case. More than forty works by over thirty Indigenous artists from around the world—North America, Australia, the Pacific Islands, Greenland, and Japan—describe the effects of nuclear bomb testing and uranium mining on themselves, their communities, and the environment through paintings, sculpture, films, and photographs.

One striking feature of this exhibition, despite the artists’ different cultures, is that there doesn’t seem to be a hard separation between the three elements of the individual, the community, and the land. There is a unity of experience and conviction that makes the art all the more powerful.

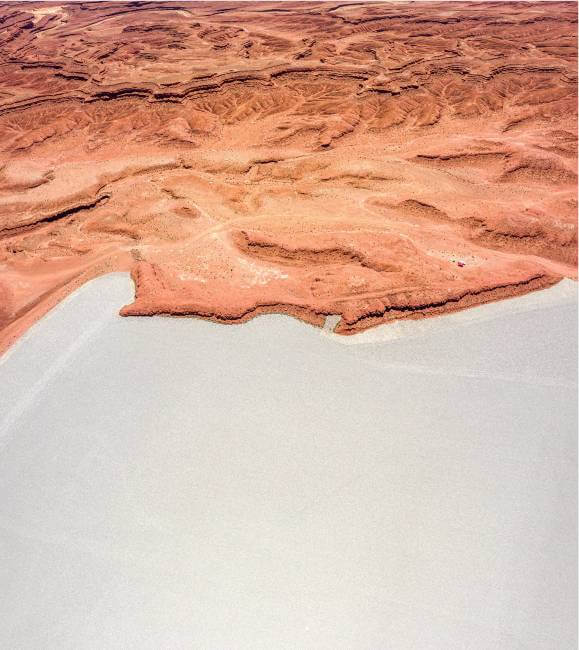

On the wall by the entrance to the exhibition is a large painting by Bolatta Silis-Høegh (Inuit) from Greenland. Outside (2015) depicts the artist’s reaction to the news that uranium mining would be permitted in southern Greenland, the agricultural “pantry” of the country. The self-portrait of the naked and vulnerable artist features a bloody sheep’s head in place of her own—the sheep’s head drips red, as does Silis-Høegh’s belly. The white figure is set against a dark blue background, which suggests an ominous landscape. The painting is unified by wild and loose brushstrokes, which conveys the sense of a solid body as well as the despair and devastation the artist feels.

From the entrance, the viewer can glimpse what appear to be long wooden sticks hanging in mid-air, which immediately bring to mind a lightning storm or a nuclear explosion in which the trajectory of atoms move in lines through a radioactive cloud, caught a second after detonation. Walk closer and it becomes apparent that the sticks are handmade traditional wooden spears—550 in all—aimed in all directions with a glowing naked light bulb hanging low in the middle. On the ground, wooden bowls are set in concentric circles.

This sculpture, Kaluta Tjuta (Many Spears) (2017) was constructed by the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands Art Centre Collective, a group of artists from the northern tip of South Australia, in response to the nuclear bomb testing on their lands during the 1960s.

While the spears were contributed by elder men, the wooden bowls, which appear to be about food or nourishment, were made by women. The light from the electric bulb casts shadows from the spears over the yellow walls of the museum room, which has the effect of electrifying the entire space.

It is one of the most extraordinary sculptures I have ever seen—the more I looked at it, the more resonances I felt. On seeing the spears and bowls, my mind oscillated between two poles: the traditional world of the Anangu and the radioactive cloud of the bomb. In this one sculpture, the same objects held these opposites.

Kaluta Tjuta is accompanied by a six-channel video installation that shows the careful construction of the spears and bowls as well as views of the APY lands. One video chronicles local people speaking of their experiences during the nuclear testing at Maralinga, an unknown phenomenon to them at the time. One woman asks, “Were we wild dingoes to them [the bomb testers]?” Though the wall plaques and the videos add great context, what’s remarkable is that the viewer doesn’t need them to understand the piece on an intuitive level.

The artworks by Silis-Høegh and the APY are just two of many fascinating pieces. The exhibition also includes a traditional Aboriginal dot painting of a mushroom cloud by Hilda Moodoo (Pitjantjatjara) and Kunmanara Queama (Pitjantjatjara); absurdist photomontages by Ivinguak Stork Høegh (Inuit); documentary photographs by Will Wilson (Diné); and a wonderful sculpture by Kohei Fujito (Ainu) that showcases a star-shaped structure of iron spirals with thorns and a painted deer’s head.

Artists of all kinds, in particular, will be encouraged by this mind-blowing show, in which self, community, the land, and tragic experiences combine to make art of the highest order.