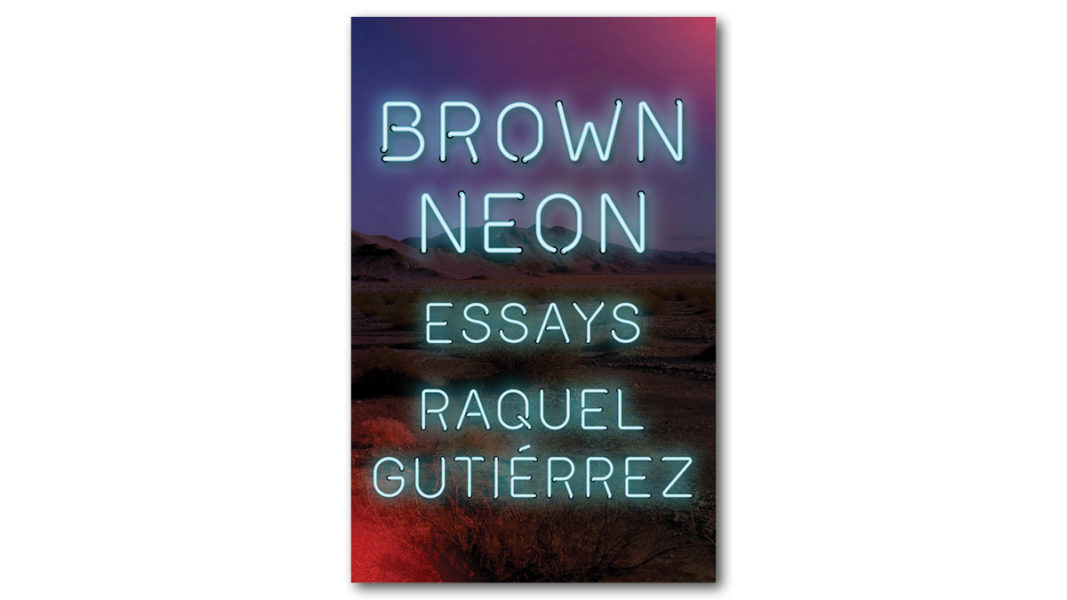

Tucson-based author Raquel Gutiérrez explores queer identity, creative communities, and life in the Southwest borderlands in her debut essay collection Brown Neon.

What does it mean to be a Latinx artist during the Trump era?

It’s a question at the heart of Brown Neon, a new collection of essays by Tucson-based art critic, writer, poet, and educator Raquel Gutiérrez published in June 2022 by Coffee House Press. Conceived as an ekphrastic memoir, the book covers a period of seven years starting in 2015 and addresses experiences and issues related to queer identity, creative communities, and life in the Southwest borderlands.

“I mined my life for material,” says Gutiérrez.

Clearly, there’s plenty of it.

Gutiérrez, who uses her/they pronouns, moved to Tucson in 2016 in part because she’d fallen in love, but also to attend graduate school. By that point, the Sonoran desert had been recurring for several years in readings she’d done with a psychic friend in California. “I wanted to be near the border,” they say. “There’s something about the way policies and culture manifest more profoundly here.”

Throughout the book, they illuminate connections between time spent in Los Angeles, where they were born and raised, and their time in the American Southwest. “I wanted to tether Los Angeles to Southwestern culture,” they explain. “There are a lot of people in LA with roots in the Southwest, so I wanted to think about how those connections are maintained.”

Gutiérrez earned an MFA in creative writing at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Starting the program when she was forty years old, she’d already spent decades immersed in various forms of creative expression, including art, music, and zine culture—despite hailing from a part of LA where she says few people had formal experiences with arts and culture.

Early on, family time fueled Gutiérrez’s creative interests.

Every month, Gutiérrez would go with her mom, who immigrated from El Salvador, and her sister to community libraries to “load up on books” by authors like Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and Paula Danziger. She’d watch television shows like Happy Days and Little House on the Prairie with her family, reflecting something Gutiérrez calls their “impulses towards assimilation.”

Later, she discovered the queer and feminist DIY aesthetic of the ’90s zine scene. “Zine culture was a way to learn about people and connect with people, which made a powerful impression,” she recalls. At the time, collaging and writing her own prose provided a means of self-expression. “It was a way to communicate about marginalization and being a kid of color amid dominant whiteness.”

Today, those themes are still reflected in their work.

Gutiérrez’s debut essay collection centers on her “butch family tree” and a life filled with artists, writers, and musicians.

Writing the essays was healing, according to Gutiérrez, who describes feeling like she’s had to hide herself because of the inhospitable culture and society we live in. “There’s a mysticism to Brown Neon,” she says. “I called in the realities that I wanted to have called in with love for art and visions of friendships and collaborations.”

Brown Neon is divided into three sections and includes a total of ten essays, including some that were previously published. “I wrote it as raw material, then organized it as a structure,” Gutiérrez says of how the book came together.

It opens with a section titled “Llorando Por Tu Amor” after a Rebekah Del Rio lyric in the 2001 David Lynch film Mulholland Drive. “She’s this ambiguous Latinx chanteuse who sings her heart out then dies,” explains Gutiérrez.

“It’s a metaphor for Latinx artmaking under the white gaze and what it means to be fully committed to artmaking in a space that would rather extract your power and leave you drained and dead onstage—but also an anthem of queer Latinx longing,” they add.

In recent weeks, Gutiérrez spent time in Marfa, Texas and presented a reading from Brown Neon at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tucson. Previous experiences with formal art spaces include paid internships at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Along the way, they’ve honed their own ideas about art and its environs.

“I love the contradictory nature of art, how alienating and inviting it can be,” reflects Gutiérrez. “Sometimes people have such a poverty of imagination about what art can do, and sometimes art plays a part in reinforcing prevailing structural powers.”

Gutiérrez says she’s already thinking about future projects, including several imbued with cultural criticism. “I’m dreaming of writing a novel about ’80s-era Tucson,” she says, adding that she’d “love to write a butch portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe.”

For now, readers can turn to her debut essay collection and the conversations the book prompts about relationships, intersectionality, land, artmaking, and contemporary culture.

“I just wanted to be honest,” Gutiérrez says of Brown Neon. “I offer my story as a blueprint for how to live a messy life and benefit from it.”