southwestNET: Shizu Saldamando

May 18 – October 13, 2019

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale

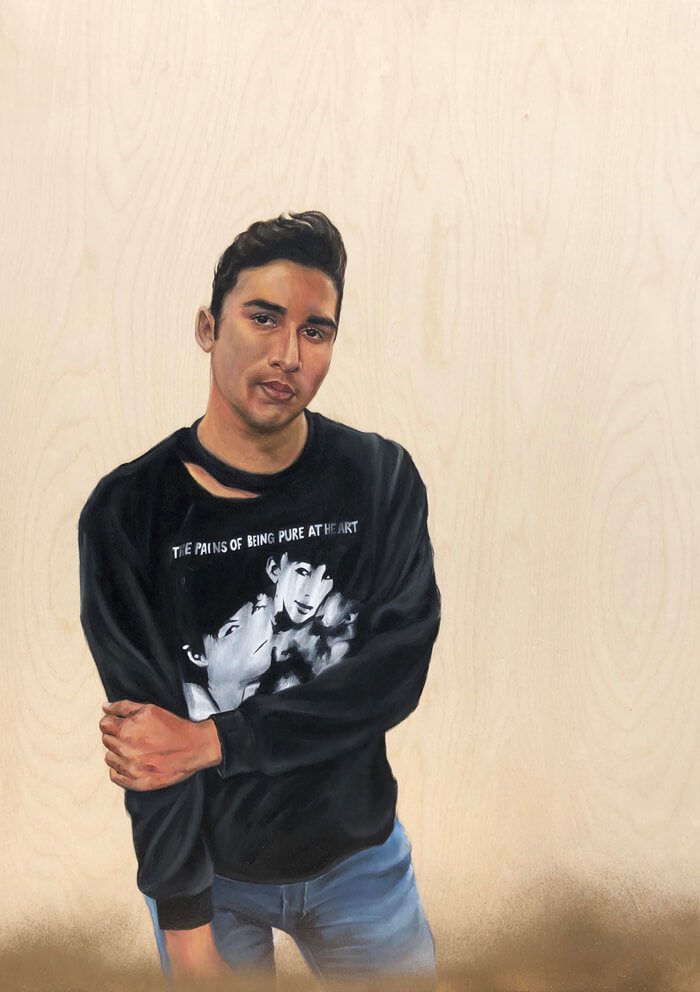

Unblinking yet familiar, the young woman’s eyes broach a question: what are you doing here? Painted in oil on wood panel, the grain visible behind a figure seemingly excised directly from a world all her own, Sashiko (2018) has luminescent hair; the fabric of her black shirt is somehow both persuasively sheer and notably painted. Teasing the boundary between photorealistic and painterly, the woman could be a half-remembered acquaintance passed on the street. And yet she’s isolated, too. Divorced from her reality on an otherwise bare panel, she forces the viewer to meet her halfway.

Sashiko greets me as I enter the gallery for Shizu Saldamando’s show, held at SMOCA as part of southwestNET’s series showcasing mid-career Mexican and U.S. artists from the Southwest. Hushed and intimate, each work seems to demand all of one’s attention, a bid made more poignant by Saldamando’s insistence on portraying friends and family and, according to the wall text, “refus[ing] any notions of subjugation” in the artist-subject relationship. A multifaceted artist of Mexican American and Japanese American heritage, Saldamando focuses on “often-overlooked communities of color: punks, queers, activists, and artists.”

Her show delivers its own compelling diversity of style, with two looped videos and twenty-one paintings using combinations of graphite, oil, colored pencil, spray paint, and glitter. Her portraits are exquisitely detailed windows into the minutiae of her subjects’ dress and facial expressions, each rendered on stark backgrounds of blank canvas, paper, or wood. In a looped video installation, Joe’s Catharsis (2019), we see only the subject’s back, accompanied by heavy metal music. He drinks; he dances; he rocks out; he pumps his fist: we see everything and yet nothing that defines him.

In the paintings, some of the figures look out, confronting or welcoming viewers with variable expressions of reproach, challenge, curiosity, or acceptance. Others do not seem aware of our gaze at all. There are at least two kinds of intimacy in these works: theirs and ours. In Tiffany and Kathie (2019), two women slump together on a bed; they look at a cell phone in one’s hand, while the other holds a disposable cup tilted against her leg. The coffee may be gone, but she’s not yet mustered the energy to toss its vessel. Is the moment one of comfort or disquiet between the couple, as they stare so intently at the screen? Either way, the moment is their own.

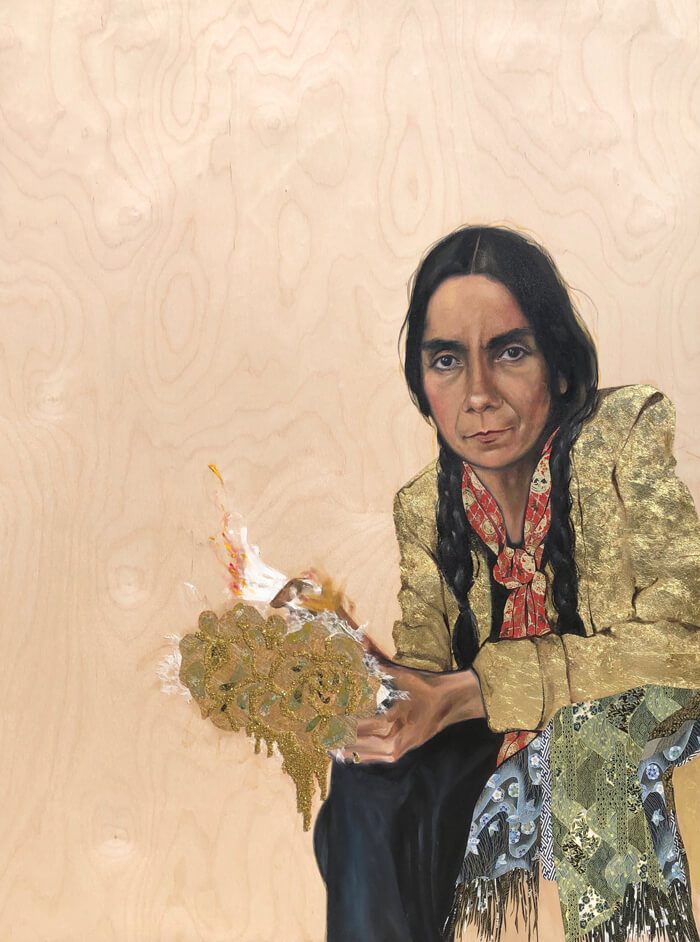

Particularly striking in Saldamando’s work is this intermingling of intimacy and austerity. Grace and Ira, Golden Hour At and Despite Steele Indian School Park (2019), one of the highlights of the show and one of its larger portraits (forty-eight by seventy-two inches), dominates the wall. It extends past the boundaries of the canvas, gold dust and leaves shimmering over the wall as if blown by an insistent breeze. The woman looks pointedly out, while the boy stares off to the side, leaning against his seated mother’s knees, his fingers digging at unseen soil. He may remain unaware of the history of horrors perpetrated against Indigenous children and families at the Steele Indian School in Phoenix in the last century, but the mother, sitting under the haunting suggestion of a tree, certainly knows.

While the description of the show asserts that Saldamando’s portraits present those who are “underground” or on the margins of mainstream society, what they actually seem to represent is how Others can be made familiar, and that each of us has the capacity to come into meticulous, sharp focus, no matter our place in the world.

What are you doing here? the painting asks again as I leave. I came here to see you, I answer, and myself.