Museum of International Folk Art, Santa Fe

July 9, 2017 – January 21, 2018

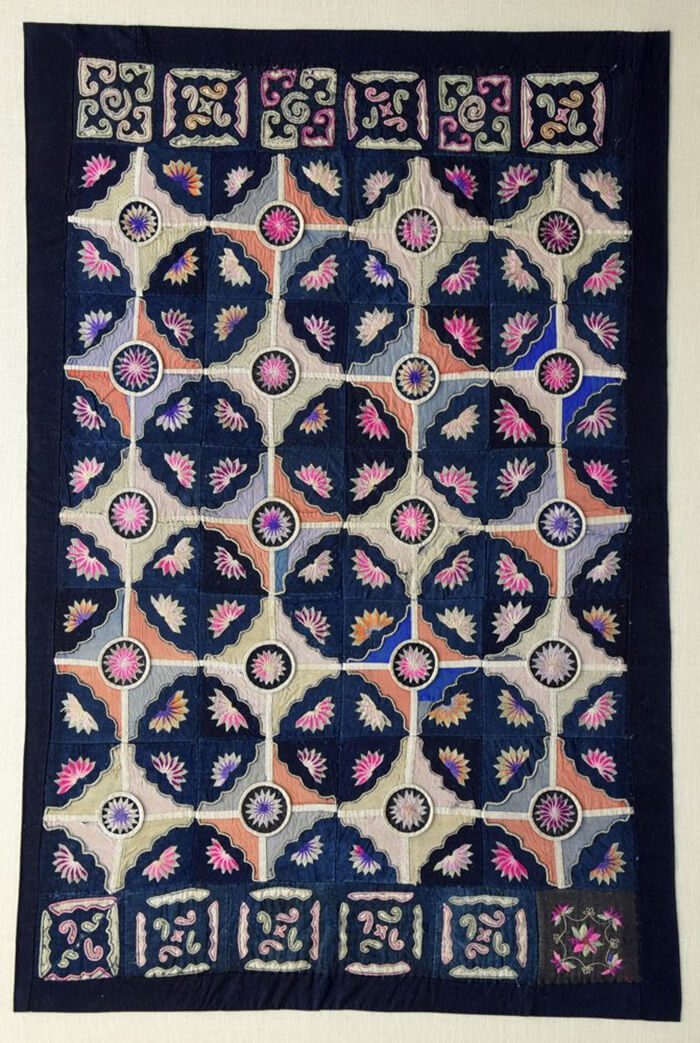

Complex patterns unfold for the viewer and richly reward time spent looking in Quilts of Southwest China. The curation of this show, which includes textiles dated from 1900 to contemporary times, expands our understanding of the social, historical, political, and geographic aspects of how these objects came to be made, preserved, collected, and displayed.

Celebrating the primacy of the handmade, this exhibition offers quilts, shoes, aprons, hats, sewing wallets (needle books), baby carriers, even diaper pads, made in rural China by women who belong to various non-Han ethnic groups. This show opens up worlds that we in the West are practically unaware of, with maps, videos, and statistics on groups such as the Zhuang (the largest minority) and Miao (also known as Hmong in southeast Asia and the U.S.). These groups are spread across several of China’s provinces and autonomous prefectures.

A useful wall text clarifies iconography. Dog teeth and centipedes to ward off evil; frogs as a symbol of fertility; and all manner of fruit, flowers, and animals evoking plenitude and well-being. Iconography is important in a culture with a language rooted in ideograms rooted in pictographs, blurring the lines between spoken, written, and illustrative. The Chinese word for fish is homophonous with the character yu, meaning abundance, thus leaping fish appear often. Two fish circling reference the philosophical concept of the two complementary forces of the universe being in balance.

The materials—cotton, wool, silk, and sometimes paper cut-outs—are combined via quilting, stitching, embroidery, and appliqué. The perfection of the stitching embodies a form of attention often disregarded in our society. Many of these pieces take one or two years to complete, offering an intimacy linked to the daily life of the makers. Steeped in the intentions put into them—made for a beloved child or grandchild and expressing hopes for good fortune, longevity, prosperity, health—these works transcend the decorative.

Even in the contemporary world, societies can transform so quickly and completely that an entire folkway may disappear. Wars, famines, droughts, industrialization, even improved standards of living may, between one generation and another, cancel out practices that had survived for millennia.

Quilting or patching involves putting together multiple sections, usually squares or diamonds. The repetition of the grid contrasts with the lively forms in each panel, creating an interplay between a fixed form and animated invention and variations within it. As one wall tag suggests, we see “stitches so regular, they might be mistaken for machine stitching.” But this human precision and focus is wedded to a sophisticated visual imagination, dancing between old and new, between fixed structure and free invention. Hanging on walls in a gallery, these works confront the same fundamental challenge as any artwork: how to enact freedom in a limited field, how to assert one’s experience within tradition, how to assert one’s identity, collective and individual.

The history of humans is a history of migrations. In Women’s Work: The First 20,000 Years, Elizabeth Wayland Barber shows that facts about women’s place in prehistoric societies are not totally effaced; they “have survived in considerable quantity, if we know how to look for them.” Even in the contemporary world, societies can transform so quickly and completely that an entire folkway may disappear. Wars, famines, droughts, industrialization, even improved standards of living may, between one generation and another, cancel out practices that had survived for millennia. Here in the Southwest, we benefit from the “discovery” by outsiders of the native crafts, such as pottery; tourists at the turn of the last century began to admire Southwestern pottery just as it became impractical for Indigenous people to make pots for home use when they could now buy unbreakable plastic or metal industrial items. The same dynamic happens globally, and so it did in China, more recently. Great-grandma’s bedcover is replaced by a shiny, new machine-made one. Yet, traditions survive; ceremonial objects, things made for dowries, weddings, births, carry an enormous nexus of cultural memory.

A non-majority group in a powerful nation-state can remain unspoken. (It is certainly true in southeast Asia, in my experience, with the invisibility of the “mountain tribes.”) A similar neglect seems to have been in effect in China until recently. Today, there are museums in China dedicated to Tangible and Intangible Cultural Heritages. Institutions are important in preserving and calling attention to the heritage of humanity. Santa Fe’s Museum of International Folk Arts has one of the top ten textile collections in the world. The show includes works loaned by local collectors and from Mathers Museum of World Cultures at Indiana University and the International Quilt Study Center and Museum at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. To see more, check out the Quilt Index (quiltindex.org), a digital repository of images, data, and stories about quilts and their makers around the world.