Antonia Fernandez, Peacock, 2018, oil on canvas

National Hispanic Cultural Center, Albuquerque

March 8 – August 4, 2019

Qué Chola is an homage to the characteristically Chicana figure of the chola. The show features street photographs and paintings inspired by old snapshots, plays on pin-up ads and Lotería cards, constructed photos, and graphic art. It’s natural that, across forms, portraits predominate. Who is La Chola? Curator Jadira Gurulé contends that she resists—and that we should resist—easy definitions. Cumulatively, these images support that contention. There is no one chola. Yet there is at least one quality shared by just about every woman represented: she stares squarely at the artist, at the viewer, at whomever happens to be looking.

This is true of the young woman flanked by, but clearly independent of, her homeboys at the show’s entryway. From their dress—the baggy pants, the chola’s hoop earrings, one cholo’s flannel buttoned all the way to the top—to their stances, to the forty-ouncers in paper bags at their feet, these airbrushed, foam-board figures are both classic and stereotypical. La Patsy y Los Homeboys (1996) is from a body of work that Texas artist Gaspar Enriquez created to document the Chicano world of his childhood, and three additional pieces (all portraits of individual women) are featured over the course of the exhibition. The hazy precision of his airbrushing, along with larger-than-life formats and solid, bright backgrounds, calls to mind the aesthetics of lowrider culture. Staggered from room to room, Enriquez’s works act as something of a narrative spine for a show that explores its subject over time but is not structured chronologically.

Another, perhaps less intentional, frame for the show is the voice of Lauren Poole, playing Lynette of Shit Burqueños Say (2012). Blackout Theater’s videos occupy a small room, but their sound permeates the exhibition space. While admiring Valerie Bower’s 2017 photographs of three intense young friends in LA, I could hear Lynette in the background, going, “Do you want a coke? Do you want a coke? Do you want a coke?” (The joke is that local vernacular uses “coke” to refer to any soda; on the third ask, Lynette is offering Pepsi.) If occasionally distracting, the looping soundtrack pushed me to reflect on the complexity of vernacular—from the use of coded language as a form of social resistance to the double-edged sense of belonging and exclusion that can result from speaking the language of a region or subculture.

Identity is a performance, many of the works here seem to say, but that doesn’t mean that it can be slipped on and off like a Halloween costume. Fashion alone does not earn belonging, and while the chola style may be distinctive, it has never been static. This is one reason I found myself drawn to Miguel Gandert’s photos of 1980s Albuquerque. Instead of emphasizing the sharp lines often associated with la chola, these portraits tend to reveal the softer edges: hair feathered, not ratted; eyes outlined, but not winged; eyebrows sculpted and penciled, but not plucked bare and redrawn. In Dimples and Stoner, Albuquerque, NM (1986), a woman in white smiles, her relaxed eyes betraying a sweetness that is not to be mistaken for weakness. Behind her stands a man in flannel and a stucco wall covered with graffiti tags.

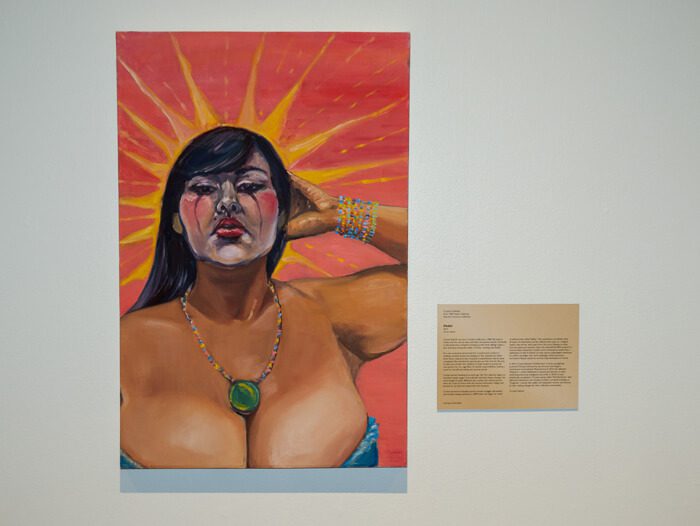

Of all the works on display here, Crystal Galindo’s Poder (2012) least fits the stereotypical image of the chola—but this is not why it held my attention. The subject is a Chicana haloed by yellow streaks of light that evoke both the Virgen de Guadalupe and the Statue of Liberty. Her face is heavily made up, the foundation so white that it floats off the light brown skin tones of her neck, and black streaks run down her cheeks like mascara bleeding into tears. In the foreground, the slope of her mountainous cleavage descends to the edge of the canvas. If the painting is a celebration of real body types, of culture, it is also a depiction of the struggle inherent to forging an identity, especially when that act is one of rebellion. In its exploration of the chola archetype through the work of artists with deep connections to their Chicano communities, Qué Chola offers outsiders a glimpse into that struggle.