Melanie Walker is an artist based in Boulder, Colorado. She works nearly equally in the worlds of photography and public art, with each realm informing the other. She is widely known for her collaborative projects with her partner, George Peters, that involve fantastical kites and extensive installation works. Her most recent solo project, Song for My Father: A Posthumous Collaboration, is a photo-based project rooted in the archives of her father Todd Walker’s 1950s career as an advertisement photographer—the job with which he supported not only his family but his personal practice as an artist.

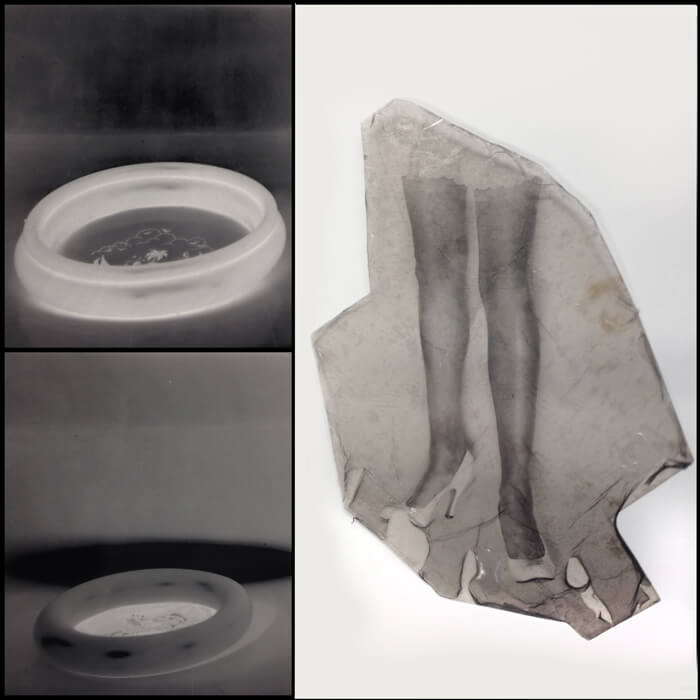

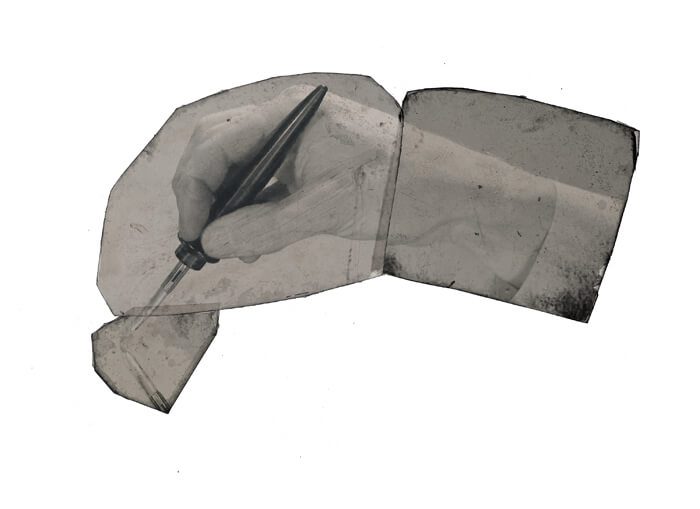

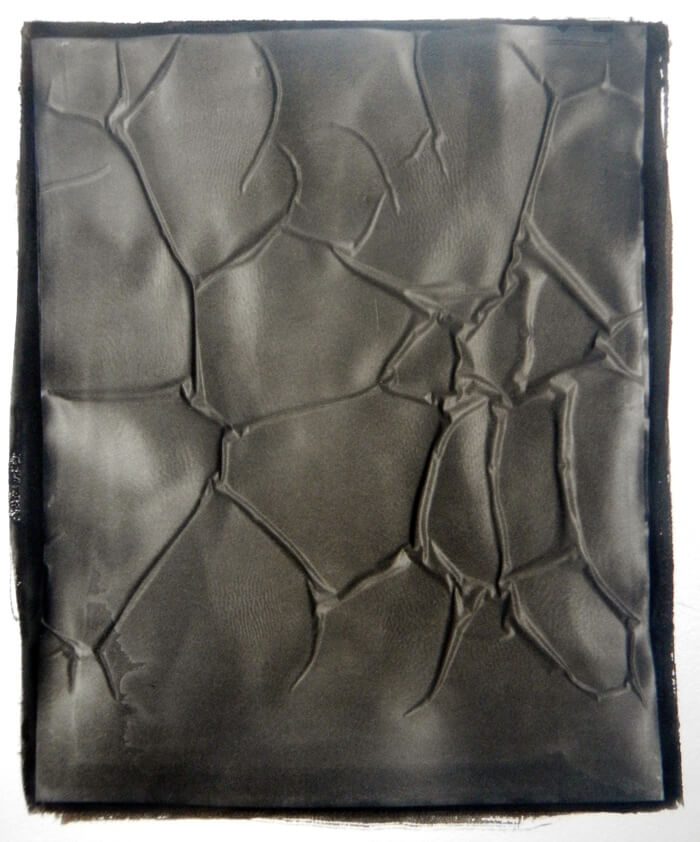

The images are created from her father’s aging and deteriorating negatives, which have been cut and reassembled into collages and reprinted in a way that reveals the flaws: the wrinkles, folds, and tears caused by the elements and effects of time. When I first spoke to Walker about the work, perhaps a year and a half ago, she framed the project around a new term that is now widely accepted into the vernacular, the Anthropocene. It is said that this era—defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “the period of time during which human activities have had an environmental impact on the Earth, regarded as constituting a distinct geological age”—began in the early 1950s, around the time Walker was born and the time that her father was working in Los Angeles advertising. Upon her discovery of the archive of aging negatives, she was struck by two things: the physicality of the objects and the imprint of a particular time in which society and the environment became interconnected in their trajectory towards great change.

Walker speaks of her father’s negatives as “fossils of the Anthropocene,” an uncannily accurate observation. As the term for our current geologic era becomes more ubiquitous, so are the artistic and photographic projects about the effects of the Anthropocene. Many emphasize physical changes to the landscape or the realities of climate change. In Walker’s new body of work, she explores the nascent years of the epoch and the activities of burgeoning consumerism from which it was born. Images of ladies’ stockings, shoes, bikinis, rubber tubing, and mid-century furniture seem just as flattened and foreign as impressions in mud from primordial cephalopods from the Mesozoic Era. Evidence of previous times has a tendency to be understood in abstract terms—enough to prove existence but also to remind us how the world evolves. Walker’s project functions in much the same way.

To see more of Melanie Walker’s work, visit her website at melaniewalkerartist.com.