Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe

September 28 -December 2, 2018

Phil Binaco’s recent body of work was inspired by a poem by W. H. Auden, “September 1, 1939,” written on the eve of WWII. It is full of dismay at the deceptions and lust for power evidenced by those in global authority, and Auden’s poem still rings true. Yet Binaco, seeking a higher authority in our own dark times, gathered up Auden’s words from the last lines:

May I . . .

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair

Show an affirming flame.

The artist, responding to the image of an inner rising flame and the power of art to prevail against political dysfunction, has created a series of encaustic paintings of great aesthetic beauty and immense subtlety.

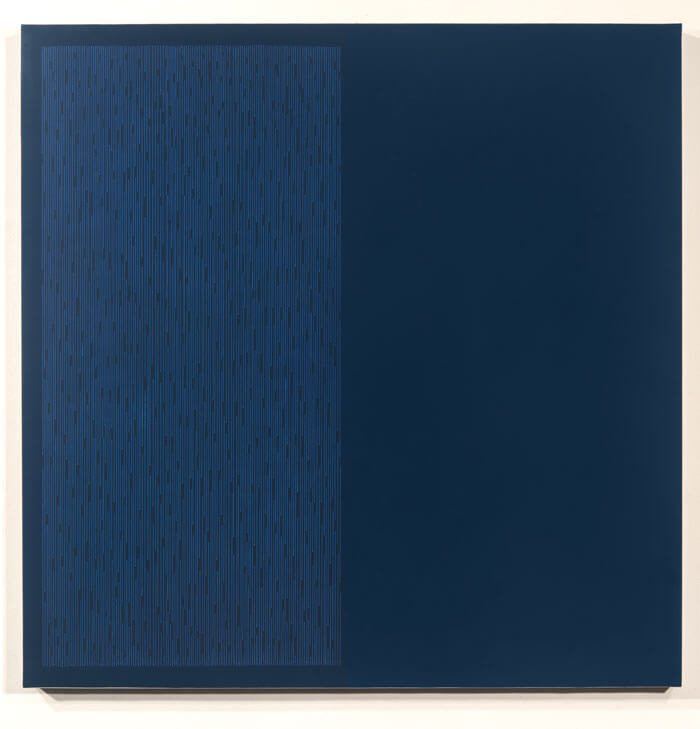

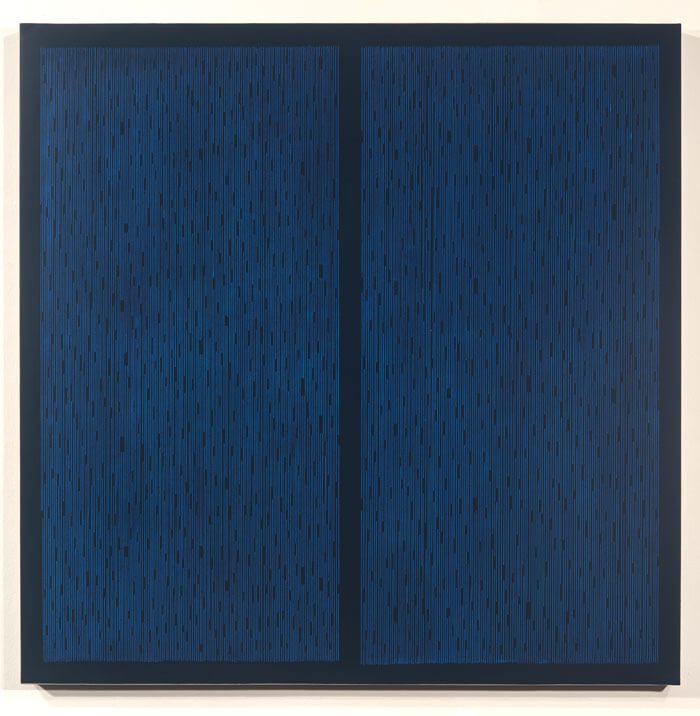

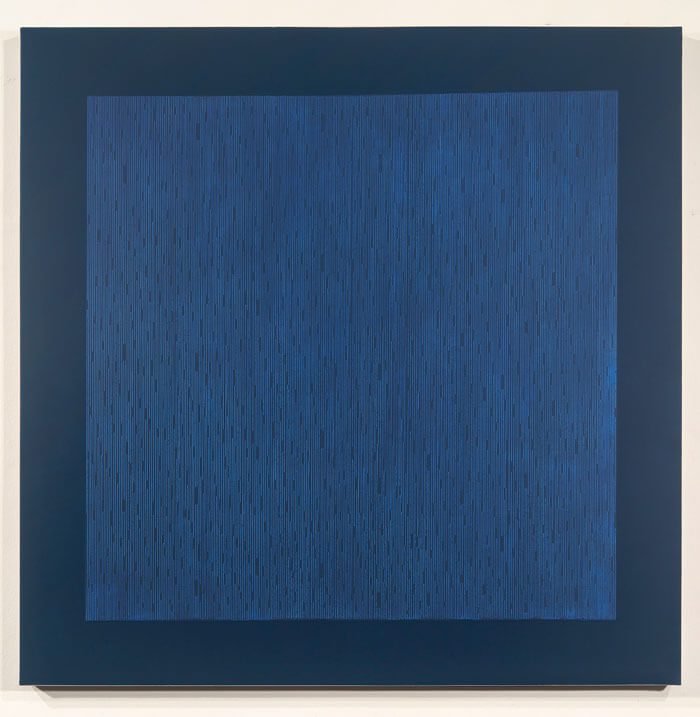

What I found so riveting as I studied the eight paintings in the gallery—all encaustic on panel and all the same size—was the obvious rigor involved in their making and the unusually coherent nature of this work that delivered its visual messages with a fierce sense of purpose. An intense formality is one of Binaco’s organizing principles, but it doesn’t necessarily ensure that a certain kind of luminous depth will quietly appear to breathe up and out of the artist’s silken, tightly controlled surfaces with their dots, lines, squares, and rectangles. The late Arden Reed wrote in his last book, Slow Art, “Phil Binaco’s paintings are not so much objects as events. Rather than simply looking, we experience them across time.”

The viewer, in a sense, has to stop time—impossible, I know—but the more one looks at the work in The Affirming Flame, the quieter the world gets, the more slowly the minutes pass, and then the phenomenological effects take over. The sheer perfection of the artist’s surfaces is a given, but underneath are intensely subtle and diffuse waves of color that seem to breach the surface, then recede into the delicate order that contains and informs the nearly subliminal chromatic blushing. It’s as if Binaco was uncovering buried layers of his own psyche, liberating the inner logic of his life and his career as a painter, and, by extension, letting the viewers reveal something of themselves.

Because the artist’s work is so overtly formal and so phenomenologically fragile, the viewer has to make constant adjustments in approaching a painting and then achieving a certain distance from it, and it is the intimacy of one’s relationship to each of Binaco’s works that appears as a kind of revelation. The same thing happens when I look at the early grid paintings of Agnes Martin: I am taken by their precision and their poetic nuance in equal measures. It’s no surprise, then, to find out that Binaco has been inspired by Martin’s work. There is a similar submission to the random effects of light trapped and then released through the meticulous process of making a painting and through the serendipities that occur at the conjunction of the physical and the metaphysical.

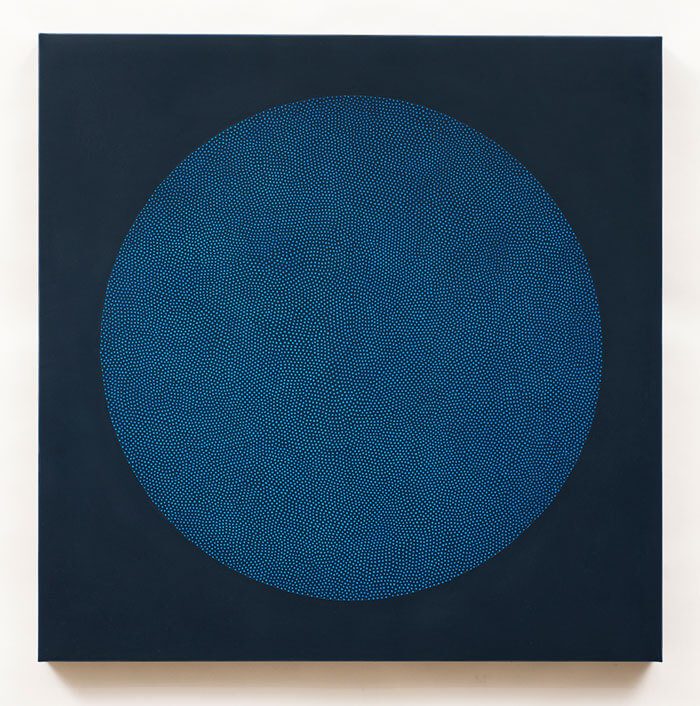

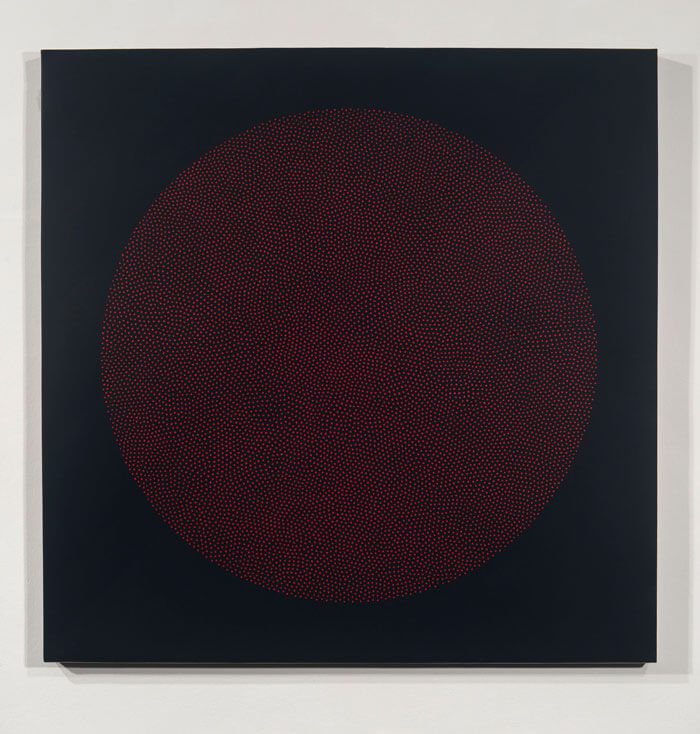

While most of Binaco’s paintings are composed of lines and mysterious spaces, three of the works utilize a circle in the center of a square—Black Ellipse, Indigo Ellipse Series No. 4, and Red Ellipse No. 3. The red and the indigo ellipse paintings possess the strongest examples of Binaco’s passionate sense of order. Red or blue dots are incised in the encaustic surface, and they create a texture in very low relief and a contrast of suggested movement on a fulcrum of stillness. One’s perception is held in consort with Binaco’s heightened awareness, his implied clouds of aesthetically rigorous consciousness breathing from within. The experience of Binaco’s work reminded me of T. S. Eliot and words from “Burnt Norton,” the first of his Four Quartets: “Except for the point, the still point, / There would be no dance, and there is only the dance . . . both a new world / And the old made explicit, understood / In the completion of its partial ecstasy.”