Gallery Fritz, Santa Fe

March 29 – April 22, 2019

Out There at Gallery Fritz pairs the work of two New Mexico artists, painter Terri Rolland and sculptor Jeff Krueger. Their work naturally invites comparisons, though I did not find that the artworks themselves do much speaking to one another. Instead, the independent nature of each artist’s work leaves space for viewers to enter and create the dialogue between them, finding likeness in form and materiality. Both use clay. Krueger, a ceramicist, does this conventionally; Rolland, rather unconventionally, uses clay paint. Their forms draw more easy associations, each liking a certain weighty roundness of edges and an implied connection to the natural world. The work is arranged to appreciate the iterative qualities of each artist’s practice. The artists’ similarity in approach, a “going outside of oneself,” as stated in the press release and that inspired the show’s title, is more difficult to discern from the work itself. Regardless, Rolland’s paintings and Krueger’s ceramics rest comfortably in proximity to each other.

Rolland’s abstracted landscapes draw from the shapes of the desert but remain elastically buoyant. Her colors are transfixingly vivid in their saturation, shapes pleasingly bulbous. Clay paint and pigments create textural interest that, from a distance, lend the paintings a quality like velvet, the colors so luminous and surface so matte as to give them a soft depth. Up close, their surfaces are sometimes gritty, sometimes sparkly, making a veneer reminiscent of the finishes of plaster and adobe and feeling as Southwestern as the forms she paints. Many of her paintings are grounded by the familiar blue-sky-and-red-mountain, their hues vibrating at their fluid edges. The smaller, numbered paintings on paper are iterative, and their similar forms bounce in orientation around the pictorial frame. These sketchbook-sized paintings act as studies, though they function well in sequence. Rolland’s love of comics is readily apparent, but presenting these works together adds to a feeling of paneled progression.

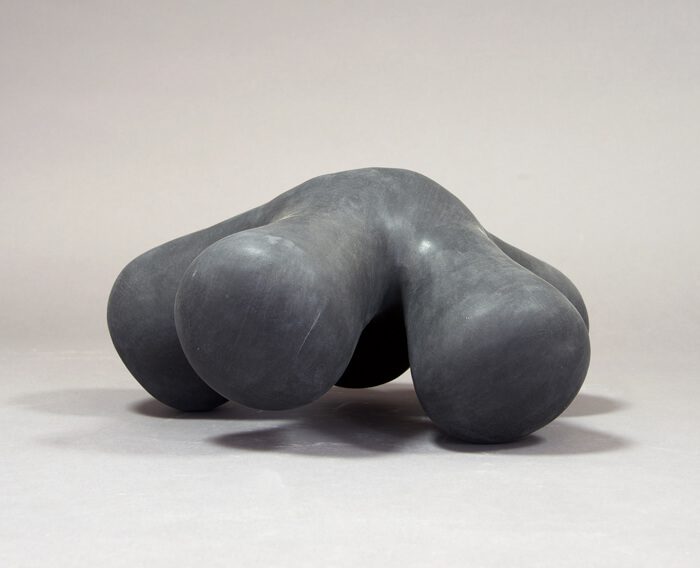

I could use many of the same words to describe Krueger’s ceramic work, though with them I mean something slightly different. His shapes are also bulbous and suggestive of nature, but Krueger’s forms remind me of the microscopic. I see pollen spores or atomic models or early stages of blastulae, biological and mathematical, but so obviously shaped by a thoughtful hand. They, too, are intentionally iterative, phasing from one form to a related other. Perhaps because of their likeness to the exceptionally small, these pieces feel almost charmingly oversized despite the fact that most could be comfortably held in two hands. And something about them wants to be held, creature-like. Several pieces incorporate a utilitarian function, like a pitcher titled American Dansk that at once references dishware and that bulbousness, or an intense-looking basin with the title Baptismal for the Death Star, or shelves and shelf-like wall pieces that easily fall into the category of art while mimicking utility. The sprawling exploration of Krueger’s work can feel a bit scattered in proximity to the tightness of Rolland’s paintings, but as a whole, his body of work reads with playful coherence.

What I am left with is another element that these pieces share, something that was perhaps made more visible in their association. Both artists’ work has a quality that I can only describe as domestic, by which I mean intended to be lived with by humans. Rolland and Krueger talk about the slowness of these works, both in the process of making and in contemplating them. I feel an affinity that the works of each artist encourage, a relationship between each painting or object and the viewer. They are works to co-exist with, to look at and relate to and develop a kinship with over time.