The stories of Marie Lorenz’s Charøn CrosSing and the power plant cooling pond, located on the same street in Austin, Texas.

Seen through an Instagram live stream, Marie Lorenz appears to be in nature, somewhere vast and shown at a low resolution. The video connection becomes choppy as soon as Lorenz’s collaborator, Melissa Brown, joins the call. They introduce themselves to the remote audience, of which I am a part, and explain that Texas’s Colorado River gets so high that it backs up into this creek, pouring up to the spot where Lorenz is standing. The shifting tide leaves huge wads of flotsam, soil, and foliage in its wake. The plan, we’re told, is that Lorenz will point her phone’s camera at the pieces of trash she finds most meaningful or interesting as she wanders around this dry gully, describing the relative location of each piece of trash. The audience will then pose specific questions related to their futures—things like, “should I quit my job?” or “what will happen in the next election?” Then, Brown will divine the trash, reading its meaning according to some intersection of its location, its cultural associations, and other contextual details in an attempt to glean answers to the audience’s questions. Inspired by the ancient soothsaying art called tasseomancy, or the art of reading tea leaves, flotsomancy is the act of reading flotsam.

Through a video so strained it appears as a succession of images, Lorenz shows us what is ostensibly the climax of the scavenger hunt. It’s a team of tiny red-orange worms swirling around, making a miniature whirlpool in the water-filled dimple of a frosty green bag of lime-flavored Lay’s potato chips, suspended within a sculptural wad of soil, goo, and trash. The video cuts out. Like a satellite, it’s as if this trash wad’s energetic force field is, in the end, too overpowering to allow for something like a video stream in its presence. For a moment so brief that it feels inaccurate to describe it, I wonder if we might never see Marie again.

Lorenz begins a new Instagram live video a few minutes later, further from the trash wad this time. She thanks everyone, encourages those in Austin to go to the closing reception for Charøn CrosSing at Dusty gallery later that night, and ends the stream.

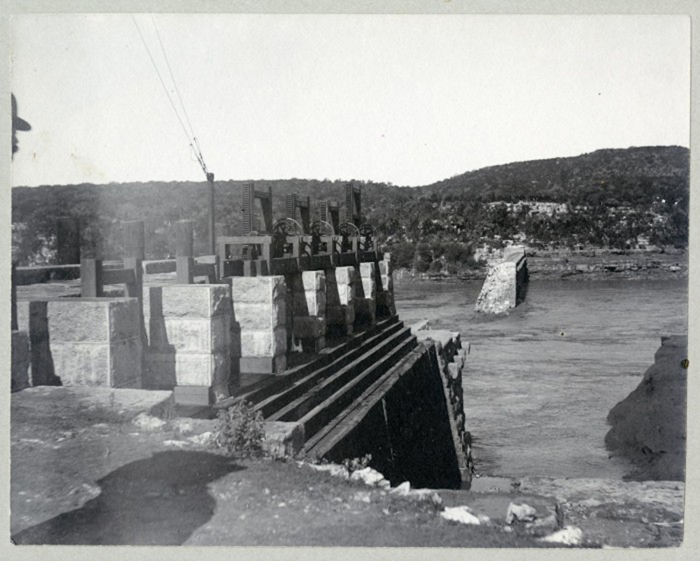

The City of Austin began the construction of the Austin Dam in 1890 along the main stem of Texas’s Colorado River. The Austin Board of Trade, led by A.P. Woolridge, initially proposed the construction project. Woolridge also owned one of the local newspapers, the Austin Daily Statesman, which regularly promoted the project. The paper posited the dam as a resource that would boost the local economy by providing cheap hydroelectric power, opportunities for new factories, and a culture of recreational tourism. In the year construction began, the population of Austin was 14,575, and the city was of unremarkable economic standing.

Constituents voted to move forward with the construction. The specific site that had been selected for placement of the dam sat atop the intersection of the Colorado River and the Balcones Fault Zone. This fault zone’s surface expression forms the eastern boundary of the Texas Hill Country, as well as Mount Bonnell Fault, which has been a tourist destination since the 1850s. Constructed of limestone rubble, cement, and pink granite from the Marble Falls quarry, the dam stood at sixty feet tall, sixteen feet thick, spanned a length of 1,200 feet, and cost 1.4 million dollars. It was a spectacle for local residents, many of whom believed this dam to be the largest in the world. However, the project’s chief engineer did not share their enthusiasm and left the project midway through its construction, citing his inability to stand by the contractors’ faulty building methods as the reason for his resignation.

The dam’s hydroelectric capacity was, at times, able to power only the city’s streetlights. While the Austin Board of Trade had anticipated that there would be a surplus of hydroelectric power resulting from the dam, the river proved too variable for a reliable flow. However, locals still enjoyed recreational activities in and around the raised waters, including fishing, boating, and picnicking.

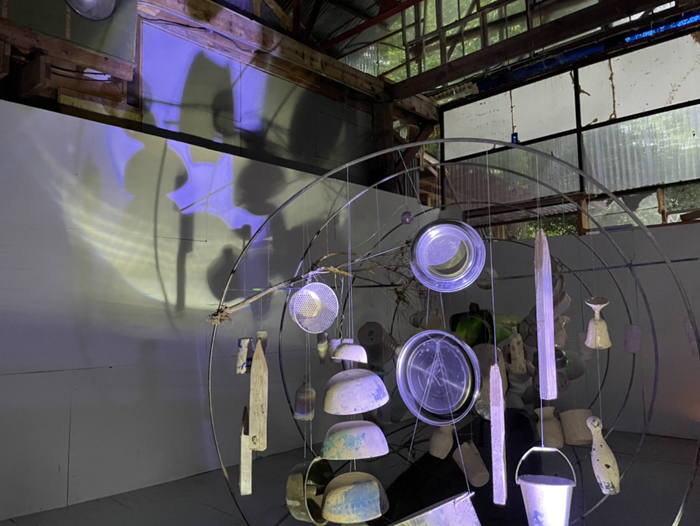

Down a long, private driveway off Holly Street, Dusty gallery’s location is indicated only by the crowd of people standing just outside the front door. There is a boat inside, but I wade through the greetings to get to it, which takes time. The floor and walls inside are a patchwork of painted plywood that contain Lorenz’s boat sculpture, which is about twelve feet long, beached on the floor. Four large steel hoops are spaced equidistant from one another, standing vertically within the concave belly of the boat. As a vessel, it all feels exceptionally inert, which in most cases would be an unexceptional characteristic of a sculpture. In this case, however, not only is it clearly a boat, whose form will always imply use, but there is an array of scavenged trash objects strung delicately onto clear fishing wire hanging from the steel hoops, each object coated in uniformly tan mud. These hoops are wide in comparison to the narrow boat that supports them, and an ambient anxiety comes with the awareness that this precarious arrangement doesn’t have the cushion of buoyancy. The hoops and their expansive shape threaten to tip the boat, whose pointed hull is occasionally made flush with the ground by only a few small wooden shims. The whole array of pots, bowls, colanders, scrap two-by-fours, plastic vessels, a bowling pin or two, hangs in mid-air. A huge swamp fan blows on the whole sculpture, not quite enough to make the trash pieces collide as they dangle, but enough to present the possibility of sound, movement, and animation in this nearly-kinetic display. Charøn, the namesake of the piece, as the press release tells us, ferries the souls of the dead across a poison river. In this depiction of Charøn, however, he is the poison river. Or rather, the poison river is the figure inside the boat.

You’re not allowed to touch sculptures, but you can usually blow on them, and in this case, you can also step on the brittle floor around the work and see the dangling trash wiggle in response—evidence of your energy’s reverberation through the boat, down the fishing lines. I feel this circuit of energy again when, after the sun sets, Lorenz and helpers set two heavy-duty studio lights on the floor of the gallery, pointing downwards into two clear dishes of water. This setup projects a watery light pattern onto the sculpture and the wall behind it. I stomp my foot on the patchwork ground next to the dishes and watch the pattern activate. The water in these dishes is dusty, but I am able to convince myself that some modicum of this dust might actually be little organisms, primordial cousins to the orange-red ones who live in the Lay’s bag.

On April 7, 1900, an upstream storm system sent a wall of water flowing down the river towards the Austin Dam. Cresting over ten feet above the dam’s upper edge, the flow overwhelmed the infrastructure and busted through the center of the dam. The falling waters burst through the adjacent power station’s windows, killing all employees present in the building as well as some onlookers. Spectators on horseback ran downstream in an attempt to warn the community. By the time the water subsided, more than fifty Austinites were killed and 100 homes destroyed in its wake. After a second attempt at construction was also interrupted by a major storm, the city applied for funding from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration through the Public Works Administration. New construction began in 1938 and finished in 1940, creating what is known today as the Tom Miller Dam.

The dam delineates the boundary between an upstream body of water now known as Lake Austin and the downstream body of water known as Town Lake, or Lady Bird Lake. Lady Bird Lake’s boundary was completed when the city erected the Longhorn Dam downstream from Tom Miller Dam. The dams created the lake, which was established for the purpose of functioning as a cooling pond for the Holly Street Power Plant.

Holly Street Power Plant ran on petroleum and natural gas. It was decommissioned in 2007, following complaints from residents of the Holly Street neighborhood detailing chemical spills and noise pollution. However, Lady Bird Lake still functions as a destination where locals enjoy recreational activities in and around the raised waters, including paddle boarding, boating, and picnicking.

My own desire to read and glean information from what is indeterminable stands out when I start wondering whether the dust is a pun, if the swamp fan is part of the installation or not (I find out later it is both). This is a form of paranoid curiosity that, in its presupposition of meaning or metaphor, calls for the boat to be a kind of book that I can read. If not for the contextual elements of the exhibition that lie somewhere between artistic intentionality and plain logistics—the flotsomancy, the swamp fan, the creaky floors, the murkiness of the projections—I would not have noticed the ways in which my experience of the artwork parallels Brown’s reading into the future. Both Lorenz and Brown indulge in our desire to read that which is around us for signs, to project our existence into the future, to make myths and descriptions that impart structure to our sensations. The local landscape is shown not as a pure and independent “outside” refuge, but instead as an extension of the human self, both in its role as our dumping ground, but also as a mirror through which we encounter ourselves and the ways we divide vastness to make meaning.

Austin is the second-fastest growing city in America, according to the American Growth Project. Drought, rising water temperatures, and high levels of inorganic carbon around Lady Bird Lake will continue to increase the presence of toxic cyanobacteria, commonly referred to as blue-green algae. These toxins have killed dogs, caused human illness, and restricted aquatic recreation. The City of Austin’s website explains, “algae tends to be more abundant near shorelines and in areas with low water flow.”

Presenting the city’s abject stuff as a collection of oracles is as much an experiment in storytelling as it is an exercise in critiquing the idea that we’ve been separated from nature. Rather than retelling an understandably common narrative in which humanity has become woefully disconnected from the natural world, Lorenz uses her work to uncover the ways in which Texans are necessarily and undeniably still tethered to the environment, albeit in non-symbiotic ways. This viewpoint exceeds the ease that cynicism affords, allowing for a certain accountability on our part. The recent history of our interactions with the natural world is made physically evident when we choose to look around, outside the normative line of sight, in the places we live. The landscape is enigmatically strewn with colorful plastics, bound together in knots, strung like mobiles from branches, delicately inlaid into the seam of a sidewalk. Formally, it’s all very sculptural. This prompts one to ask how our relationship to place might change if we were to begin reading pollution in the same way we read works of art: searching for meaning, making oracles out of the inanimate.