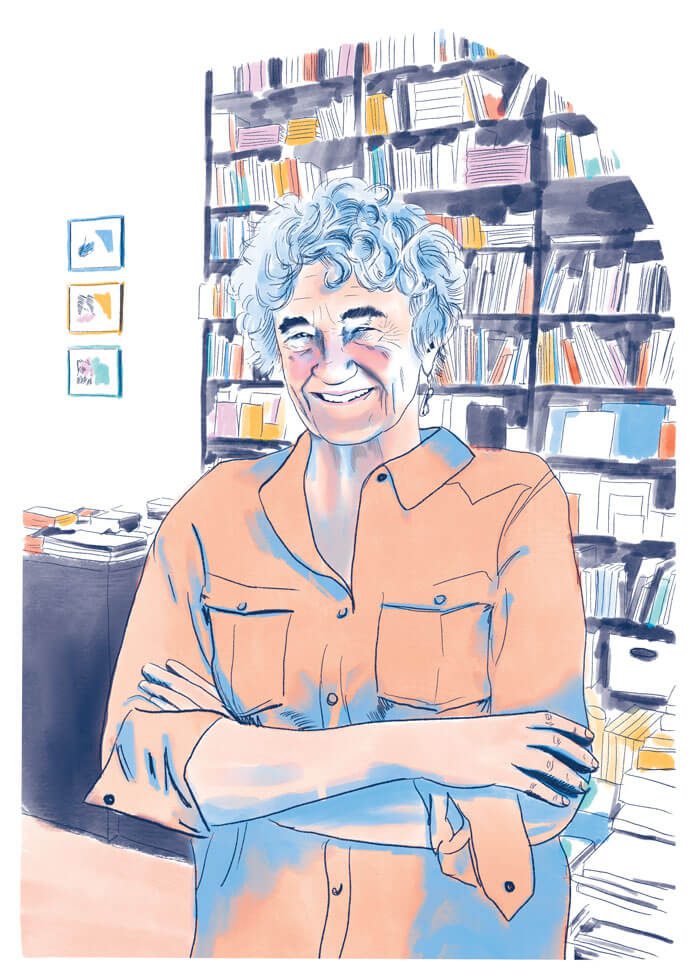

Name: Lucy Lippard

Born: New York, New York, 1937

Lives: Galisteo, New Mexico

role: Art writer, curator, and activist

quote: “I’ve always disliked the term art critic since I’m an advocate, not an adversary. Everything I know about art I’ve learned from artists.”

Lucy Lippard changed what art writing could look like, and she continues to shift it with each book she writes. Hugely influential in the artworld of New York, beginning in the 1960s with the Art Workers Coalition and later Heresies Collective, her impact on New Mexico is equally prodigious. Her writing, her curating, and her involvement with local organizations (from the Railyard Art Committee to editing Galisteo’s monthly newsletter) will have ripple effects long into the future. Lippard is a generous mentor to writers in New Mexico (myself included) and living proof that it isn’t just artists who can find a haven here, though it didn’t seem that way to her at first. Lucy visited New Mexico in 1972 but didn’t think she could “make a living as a freelance art writer here.” She came back frequently, staying with Judy Chicago and Harmony Hammond, “So,” she says “feminists led me here!” In 1992, her “activist community in New York had wilted,” and she “didn’t want to be dragged into academia.” Her mother died, leaving her with “some money for the first time in [her] adult life,” so she bought some land in Galisteo, across the creek from Harmony, and “built a hokey little (16 x 24’) house off the grid and moved here.” She’s been there ever since.

New Mexico fit into a larger progression in Lippard’s approach to art writing. She recalls, “I began writing about ecology, eco art, landscape, etc. around 1970, and Native art around 1980, thanks in part to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith and Ramona Sakiestewa. I started focusing on place, or cultural geography, in the late 1980s, after my book Mixed Blessings on multicultural art. That led to The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society, when I decided I’d better practice what I preached, here in Galisteo, which is tiny, but complicated, and raises all kinds of issues and challenges I’d never faced in Lower Manhattan.” When I asked what Lippard wishes people understood about New Mexico, she replied, “that it’s not like any other place in the U.S. and that it’s one of the very poorest states in the country. (Remember the bumper sticker ‘Thank God for Mississippi’?). That it was settled before the pilgrims hit New England, that the Indigenous presence is part of life here, that there are a lot of really good artists who have settled here to the detriment of their artworld careers… and of course everyone knows about the beauty of the land.” These associations bear themselves out in her work and in her life: class consciousness, which surfaces in her insistence that to be an art writer you simply have to “keep your standard of living low” (advice I personally find liberating), active engagement with Indigenous people and culture, and a perceived escape from the artworld.

Since moving to northern New Mexico, Lippard’s writing has grown more and more local and place-centered, focused on land use and history here in New Mexico. Her last book, Undermining, examines gravel as a metaphor and land art, among many other subjects, and her current book is Pueblo Chico: Land and Lives in Galisteo, New Mexico, since 1814, a history of the tiny village where she lives that in its last chapter “becomes a kind of memoir about the socio-dynamics of the village.” For the last twenty-three years, Lippard has produced and edited the village’s monthly newsletter, El Puente de Galisteo, so Galisteo residents are used to being written about by one of the world’s best-known art writers.

It’s nobody’s fault but my own that the idyllic relaxing life I’d pictured lasted maybe a year.

I’m sure she has more writing projects in the works, but she’s a busy woman. “I’ve long had a bad habit of sitting down with people at a kitchen table and suddenly we’ve founded a group or an action or something. When I moved here, I swore that would stop. I envisioned a peaceful life with lots of hiking and reading. I didn’t start anything, but now I’m 82, have bad knees, and have gotten involved in too damn many things. It’s nobody’s fault but my own that the idyllic relaxing life I’d pictured lasted maybe a year.” Lippard’s coffee table, a “beat-up” gift from Sol LeWitt, is piled so high with things she’s “about to read” that her “friends complain they can’t see over it.” Her reading list is an indicative mix of the local papers, art writing, and climate theory. Things like High Country News, Brooklyn Rail, The New Yorker, The Nation, The New Mexican, The Reporter, Green Fire Times, books on climate change like Bruno Latour and Dahr Jamail, fiction, and of course, The Magazine.

For more about Lucy’s activism in the 1960s, see Art Workers: Radical Practice in the Vietnam War Era by Julia Bryan Wilson. Pueblo Chico will be published this fall by the Museum of New Mexico Press.

In the New Mexico Women column, I share the stories of women who have made and are making New Mexico what it is today, who shape the art, language, literature, land, and culture. As much as possible, I draw on these women’s own versions of their stories—my own interviews with the subjects, their autobiographical writings, their work, and whatever else I can find.

New Mexico Women is sponsored by form + concept

All editorial is directed by The Magazine

and its bylined contributors.