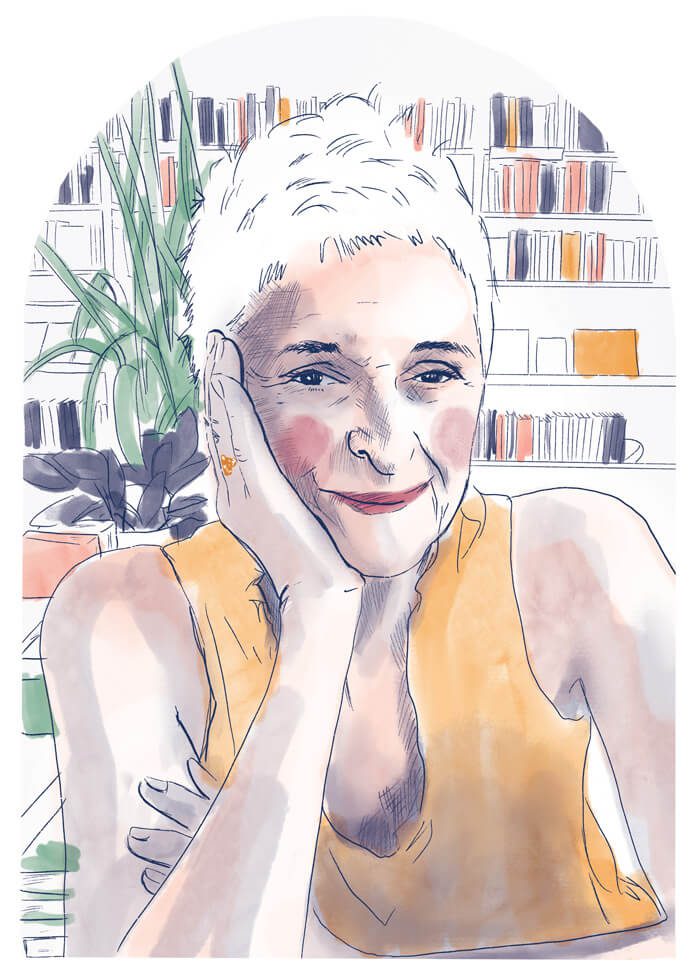

Name: Eugenia Parry

Born: 1940, Chicago, Illinois

Lives: Cerrillos, New Mexico

Role: Writer

Quote: “After thirty-three years, I could feel the land sculpting me.”

The first time I heard Eugenia Parry speak was at the 2018 closing dinner honoring Joel-Peter Witkin for the Review Santa Fe Photography Festival. Parry presented a piece she wrote about the artist, but this was no ordinary presentation—it was closer to a sermon. She used no slides, reading aloud from sheets of paper. Her agile language and powerful delivery stunned the audience, pummeling them with graphic descriptions that conjured forceful, visceral, and emotional reactions. Parry has an uncanny ability to create imagery out of what seems like thin air in her writing and lectures.

In December of 2019, Parry invited me to her home to conduct the interview for this column. She lives in the village of Cerrillos. With vigas throughout, the home’s ceiling is punctured by skylights and beams of soft light, illuminating a library and a comfortable sitting room situated in its center. We settled in to talk. After only one question—“Where and when were you born?”—she dove into the story of her early life growing up on the south side of Chicago, her Greek parents, even an anecdote about how she and Michelle Obama shared the same kindergarten teacher. She spoke so effortlessly that I hardly asked any pointed questions; the conversation offered me everything I was curious to know.

Parry is well regarded in the world of photography. She taught one of the first official history of photography classes at Wellesley in the early ’70s, creating the curriculum from scratch. She’s published over one hundred pieces during her lifetime, including essays for exhibition catalogues and periodicals and several books. In 1985, she was invited to the University of New Mexico to replace Beaumont Newhall (who wrote the book, The History of Photography, which is still in use as a textbook today) as the photo history professor. She had been at Wellesley for over ten years by that time and felt stifled by the rigid East-Coast perceptions of art history. Parry quickly felt camaraderie with her colleagues at UNM and a liberating sense of creative freedom. Of her initial time here she said, “real values crept in. Forget the money, forget the benefits, the kudos. Just go for what you think is the right thing for you. That’s not easy to do.” Once she moved to New Mexico permanently in 1986, she never left. “This place is what you make of it, and it can be glorious.”

One of Parry’s largest projects was a book called Crime Album Stories: Paris 1886-1902, published in 2000. It is a collection of short stories based on images from a police album she found in a French private collection that documents violent crimes. Many of the images are by photographer Alphonse Bertillon. The book is innovative and lauded for its experimental approach to writing about photography. I asked Parry about her creative process and if she had a routine: “No, I have no routine. I am a procrastinator; I am the worst example of a writer. I do a lot of research,” she said. She told me that once she decided to write the book, it took six years, partly because her research took her deep inside her subject matter. “I had to learn about mushroom growing, what it was like to be a waiter, the jealously of waiters, prostitution, and gender fluidity.” All researched through newspapers of the time. “Each story was a world. Each story a dismemberment,” she described. Although some of her best work is about difficult imagery, much of it is also about mystery and the life of objects.

“I think people are lonely for objects that talk back,” Parry said as she showed me a handmade potato-digging shovel. I asked her how she felt about the shifting role of images in popular culture, to which she responded with anecdotes from her days as an educator. At Wellesley, she often taught from originals and had amassed a collection of daguerreotypes for the purpose. “I remember seeing these girls in a room where all the reflections from the daguerreotype glass were on the ceiling. It was beautiful to see them looking,” she said. She also lamented the extinction of film slides, of which she had created a specialized collection for use in her lectures. Hearing Parry talk so lovingly about the slides made me wish that I could have experienced one of her lectures, which she always composed on a light table. She said, “The light table is like an ocean, and you move the boats around. I used to love to compose my lectures that way.”

Through our conversation, image after image materialized in my mind, giving life to things I had never given thought to before. Even without slides, Parry is a creator of worlds. She credits New Mexico for much of her success: “After thirty-three years, I could feel the land sculpting me—and I have done my best writing here. Why? The burden is lifted. No one gives a damn!”