Albuquerque artist Leonard Fresquez offered a unique glimpse at the possibilities of art in understanding our world. His June 2022 death at the age of forty-one marks a profound loss.

ALBUQUERQUE, NM—Albuquerque is sometimes underestimated. From the outside, it often seems all sunbleached streets and adobe façades; neon signs buzzing in the night illuminating cockroaches warming themselves on the sidewalk. It is a place easily misunderstood; you almost have to be from here to see its depth, if you’re willing to look at all.

Looking is what Albuquerque artist Leonard Fresquez did. He offered glimpses of strangeness and humanity through practices that included photography, curation, sculpture, design, and publishing via Trapset Zines (alongside Max Farber).

With an eye for the things that are at once common and extremely weird, Fresquez’s work suddenly thrusts a place like Albuquerque, his hometown, centerstage against the immovable backdrop of mystery that is life. His work offered us each a place in the frame, a way to see our home, ourselves, and our struggles as worthy—the stuff of art. His passing on June 25, 2022, at the age of forty-one marks a tremendous loss.

I first came to know Leonard through his photography. Always apprehensive about what might be called “street photography,” there was something considerably more than documentary to his work. I often wonder, when I look at other photographers’ candid photos of people—some remarkably vulnerable—what the artist offers the subject in return. It often seems like little, perhaps not even their humanity. That exchange—reciprocal or not—is one of the trappings of street photography, but then there is a different category: photos taken on the street that evince trust.

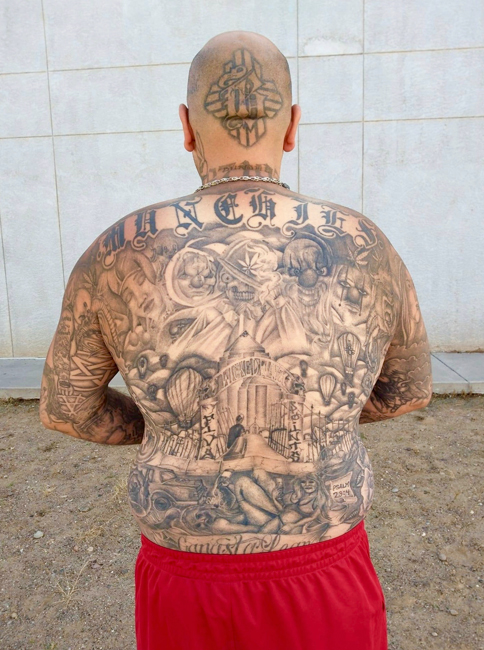

The intimacy his subjects allowed is the crucial mark of Leonard’s work—and it seems earned. A man opens his shirt to reveal his chest tattoo, all hearts and an empty banner; or a woman leans toward the camera while a flame lights her cigarette; the interiors of a bedroom are photographed in the dim light from a single bulb.

Fresquez moved in many of Albuquerque’s microcosms—the galleries and downtown DIY spaces, the parts of Southeast called the “war zone,” and the city’s strip and antique malls— and truly belonged to them all. Curious, brave, and dedicated, he collected what he found interesting, and even when you might have thought you knew everyone and had seen everything in this town, he would show you something new.

“When Leonard introduced you to someone, you’d give them more of a chance,” says Los Angeles-based fabricator and puppeteer Michael Serwich. “If they were with Leonard, you knew they’d be subversively silly and creative.” Erin Elder, an artist, owner of Gibbous Creative, and mentor to Fresquez, adds, “He had every reason to be skeptical of people, but he wasn’t. I think he really got into people, and he really let people get into him.”

Fresquez became a father at the age of thirty-four, and his son, alongside his art, seemed to motivate him to be a better person. A year later, in 2016, he published his first book, American Irrationalism. Through hundreds of photos, the book mapped the curious worlds of Albuquerque and Southern California, offering a portrait of the places that shaped him, full of both sunshine and strife.

With Trapset, he produced zines and artifacts from the likes of outsider-art legend Mark Beyer, internationally exhibited Canadian painter Shay Semple, and Tokyo-based Ken Kagami. “He was so humorous and intelligent,” Kagami writes from Japan. “For some reason, I always felt he was nearby. I was inspired by him and his work.”

Fresquez had an uncanny way of tying the knot between the aesthetic and the true in all of his work, revealing the way he drew from his own experience, struggles, and interests to create.

“I first met Leonard at a small show he had at a hair salon,” says artist and fabricator Sven Barth. “There was something about his paintings that stood out from everything else that I was seeing in Los Angeles at the time. They were raw, almost unfinished—but never contrived. They echoed his life. Some portions only had pencil marks, the paint didn’t always fill the spaces he had marked out for it. But they were honest.”

In late 2018, Fresquez curated his first museum exhibition, The New Bootleggers: Fabricating (Im)proriety, a companion show within Currency: What do you value? at 516 Arts in downtown Albuquerque. Hosted inside a bodega façade, the group exhibition featured counterfeited goods and beautiful fakes, again examining honesty and its incredibly blurry line with dishonesty. The New Bootleggers, featuring more than twenty artists, called into question authenticity, branding, and underworld economies—unlicensed but totally precious Versace sweatsuits were stocked alongside bootlegged liquor, “designer” t-shirts, and Fresquez’s own counterfeited Memphis Group furniture in a glorious and sanctioned act of total subversion.

The expansiveness of The New Bootleggers evidenced a hallmark of anything Fresquez touched. A true participant in the scenes that give rise to art—he was enthusiastic about music, always engaged in conversation, and studied art history—he seemed to know that when we are participating in art, we are participating in life.

“He believed the more people participated, the better something would be,” Elder observes. “He was always inviting people in and being generous with the spotlight.” Barth adds that “when [Leonard] came upon an idea he felt had substance, he pursued it,” which meant drawing in other people, “speaking about it with his peers, and making it real.”

That vision created new possibilities and new understandings—and afforded all of us the possibility of finding ourselves participants—as spectators, collaborators, or subjects.

“Whatever he was doing, he was an artist,” Serwich says. “He had that rare sense of someone who was vastly improving upon the things that were there, putting order to them.” The crux being that “Leonard’s life seemed to get in the way of his practice,” as Barth put it. “But living was his practice… it’s what I truly believe that art is all about—a forever evolving story you use your life to tell. It can never truly be ‘finished,’ otherwise it wouldn’t be honest. It ends when you do.”

An artist can never know the full redemptive potential of their work as they make it, something that seems to be underlined by a story that former co-director of Albuquerque’s Corpus Arts and English professor Cameron Mozafari told me. Every year, he’d teach classes on zines and small press publishing. And every year, his students invariably gravitated to Fresquez’s book in particular, leafing through pages of photographs of Albuquerque that feel both otherworldly and just like home.

Mozafari often repeats something that Fresquez had shared with him: “That all you need to be an artist is the bravery to look where most look away.”

The resonance of Fresquez’s work, and its ability to magnify strangeness and beauty, offers a nod to the way it will endure, which is some comfort in the wake of his death last month. According to the Albuquerque Police Department, he was shot and killed during an attempted armed robbery; in the weeks since, a suspect in the case has been issued a murder warrant. This devastating revelation traveled through the local arts community and well beyond. And with it, artists and friends from across the country and the globe were forced to come to terms with the passing of a person who held a vision of art and its potential for so many of us.

When an artist brings forth something about a place, in this case, Albuquerque—the waiters and watchers at the bus stop at Central and San Mateo, the exhausted face of a Smith’s grocery store shopper, the depths of an abandoned swimming pool—the minute the artist sees and represents it, this place, this world, is transformed. There is always beauty and meaning, of course, but the artist makes it recognizable.

The work Fresquez leaves behind remains an invitation to courageously seek out and articulate the substance of our lives. His books, sculptures, images, and exhibitions reveal the ordinary stuff for what it is—totally absurd and improbable, but yet right here in front of us. If we can see it, the ordinary becomes haunting. The streets, people, and moments that are already and always there are given a different life. That transfiguration is the work of a true artist, jolting us awake to a world full of holes and yet stitched together with possibility.

Donations can be made in the memory of Leonard Fresquez to Fuego Arts, a South Valley arts studio where Fresquez apprenticed in 2020. Every dollar will support future apprenticeships for formerly incarcerated adults, refugees, or others in need of empowerment and employable skills.

Find more of Fresquez’s work at leonardfresquez.art.