Since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent premature shuttering of so many exhibitions, I’ve been bombarded with messaging around virtual and web-based exhibitions, so-called viewing rooms and/or viewing platforms, and many other digital adaptations of arts programming. The formats of such exhibitions and programs have varied in structure and in quality, but all have been, on the whole, underwhelming. It’s easy to say the reason for this is the incomparable nature of an exhibition, the ritual of physically moving through a space set aside to experience visible phenomena, but it’s more generative to imagine there may be digital alternatives to the exhibition that create new ways of viewing, rather than poorly recapitulating an IRL model.

What is an exhibition, anyway? A well-conceived and well-executed exhibition adheres to or expresses a coherent concept. It’s curated according to a guiding principle, the possibilities for which are endless. An essential component of most exhibitions is the relationship between phenomena (artworks, video, artifacts, etc) and how the pieces of an exhibition relate to or interact with one another. Thought is usually given to guiding the viewer through the materials or through space. Context is created. Exhibitions are necessarily experiential. In other words, a grid of JPGs does not an exhibition make.

Setting aside the obvious impossibility of recreating the physical experience of an exhibition online, what then, does a virtual exhibition actually lend itself to? Many virtual exhibitions, both pre- and post-COVID-19 simply fall into the category of sales tools. The highly promoted and much-buzzed-about Art Basel Online Viewing Rooms (comprised of galleries that were to exhibit at the canceled Art Basel Hong Kong in March) were inexplicably lame. Viewers could flip through works Photoshopped to look installed on a living room wall. Over 250,000 viewers visited the site (and handed over their email addresses for access, how clever), but no sales numbers have yet been reported.

Before the pandemic, a virtual exhibition could record and enhance its IRL counterpart, through photographs, videos, or simulations that all fall into the category of archival materials. These digitizations document installations, or (post-pandemic) create mock-ups of would-be installations. These formats provide the possibility to spend time in close viewing (provided excellent photography) of pieces that would otherwise require physical distance due to fragility, value, or crowded gallery spaces. They sometimes provide quick, comprehensive access to supplementary materials. Gallery videos and VR simulations fall into this category. Google Arts & Culture is maybe the best-known platform for this, allowing users to clumsily click their way around Kara Walker’s monumental installation A Subtlety (2014), or Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Floating Piers (2016), which lend themselves to Google Streetview only in their massive scale. Google’s Art & Culture platform, while not presenting exhibitions per se, is worth exploring if for no other reason than the vast number of options it provides to view various collections and “experiments” (try both the desktop and mobile app versions). You’ll find each tool to be somewhat shallow and quickly exhausted, but the premise has potential. Linger long enough in the “Experiments” section, though, and you may catch a whiff of Silicon Valley bro culture trying to “hack” art (keep trying).

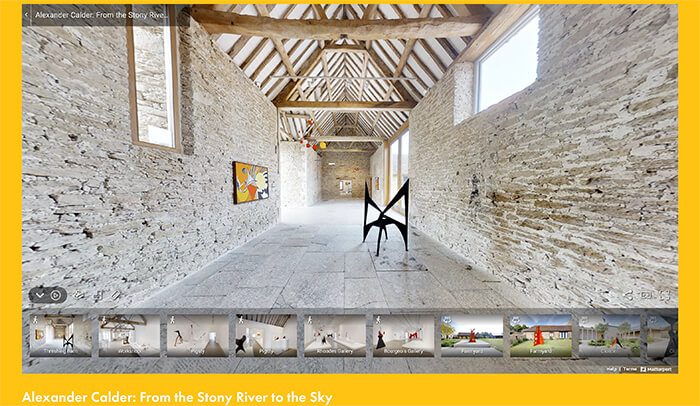

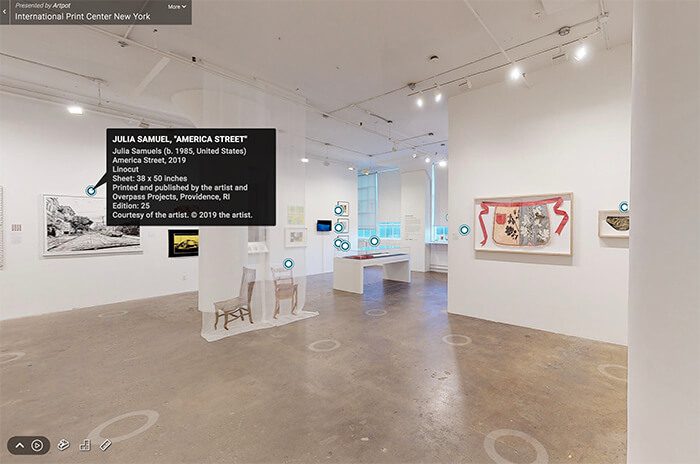

V21 Art Space provides a much better VR experience than Google’s lo-fi Streetview. Using a combination of photography, video, and laser scanning, the V21 VR experiences are much more sophisticated and navigable. Alexander Calder: From the Stony River to the Sky at Hauser & Wirth Somerset is an excellent example, but again, most of the interest lies in the remote experience of the lovely architecture and grounds. The International Print Center New York utilizes the same technology in a virtual tour of their most recent installation, with clickable wall labels that at least allow you to identify the many artists in the group show titled Homebody: New Prints 2020/Winter, but could provide much more in the way of context.

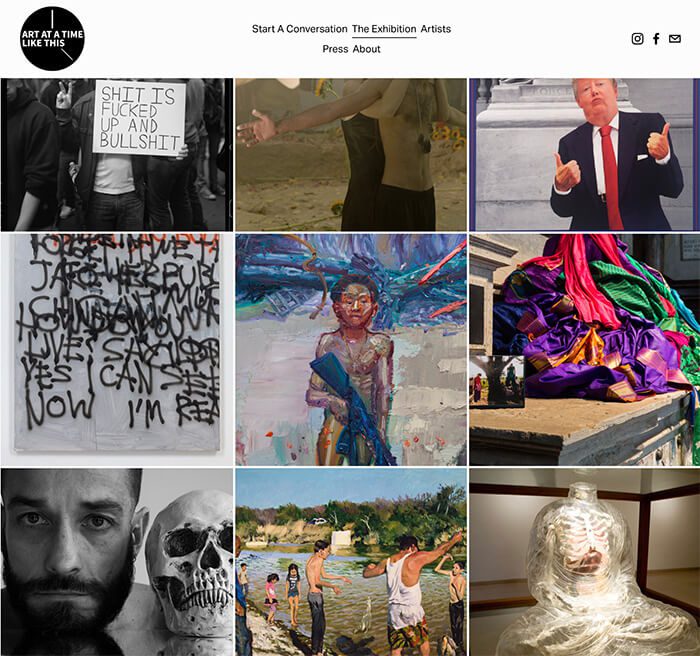

This kind of digitization is stuck in a mode of re-creation and archiving, where other examples embrace the web as part and parcel of the viewing experience. Launched within days of the pandemic lockdown, How Can We Think of Art at a Time Like This? is a web-only exhibition curated by Barbara Pollack and Anne Verhallen featuring works by an international roster of artists, along with artists’ written reflections on the coronavirus crisis. The project notes “This may end in two weeks, two months, until November, or continue for long afterward. In that vein, this exhibition will constantly expand, adding new artists regularly,” embracing freedom from the constraints of time and space.

The expansiveness the web provides is also its infuriating flaw: it is a decidedly noisy, uncurated space.

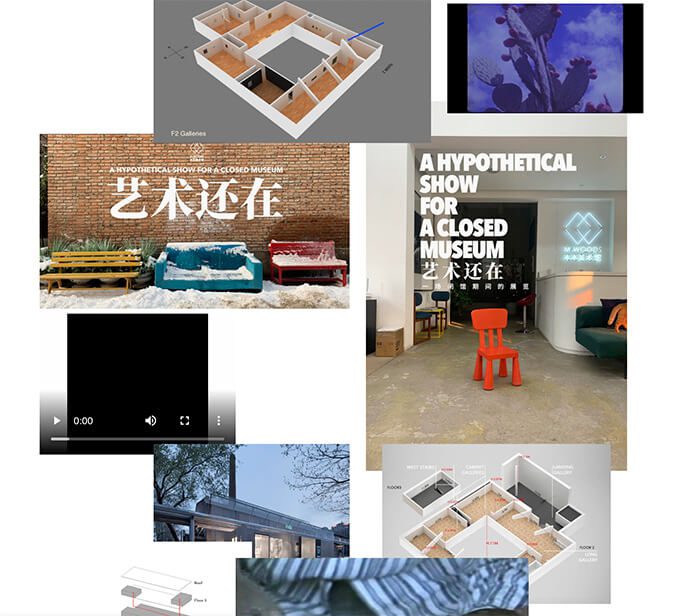

One of my favorite examples is Art Is Still Here: A Hypothetical Show for a Closed Museum, presented by M Woods Museum in Beijing. This web-only exhibition began on February 13 and also has no fixed end date. Each week, new works are added to new gallery “rooms,” comprising images, video, and accompanying texts about the featured artists and works that grow through accumulation. On the landing page, an array of images can be moved around the screen by the viewer, possibly to create or examine relationships between them. This element of the exhibition is limited, but it hints at some capabilities of interactivity and flexibility that an exhibition designed for the web may offer.

A successful strategy I’ve seen is the time-based release of video works. The expansiveness the web provides is also its infuriating flaw: it is a decidedly noisy, uncurated space. Placing time-based structures on digital projects can lasso them into focus, and video is uniquely positioned to shine in the time of web-based viewing (I personally find I rarely have the patience or focus to sit with a video work in a peopled gallery space). The New Mexico-based Holt/Smithson Foundation is releasing video works (usually available only in museum settings) by Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson every Friday through April and May 2020, for 24 hours of viewing on Vimeo and IGTV. Amanda Wilkinson Gallery, based in London, launched a series titled “Images Disturbed by an Intense Parasite,” in which an artist film is released each week to subscribers of their email list. Each video is available with a password on Vimeo for one-week installments. Some of these films may be viewable elsewhere at your leisure, but the curated, structured series provides a much-needed impetus for sitting down to spend time with them.

Overall, the current state of virtual exhibitions is rather disappointing, but there are a few promising gems out there in the cacophonous landscape of the net. As more organizations create new ways of viewing and try out new approaches to curating online, there may be more to enjoy in virtual exhibitions. In the meantime, I remind myself it’s okay to step away from the screen, to mute the many calls for engagement and stimulation, to sit outside and gaze upon the budding trees.