New Mexico artist Michelle Rawlings examines beauty through blurred visions, imitation, and purposeful psyche-outs. Steve Jansen explores how Rawling’s work speaks to the ways we identify with and move through the world.

It’s a mistake to give a cursory glance at most artworks, but this is especially the case with Michelle Rawlings’s pieces that span genres and quote several recognizable periods in art history—with peculiar gestures.

The beauty, when arriving in front of a Rawlings painting or sculpture, really can’t be argued with. The technique, the coloring, and the execution are all there. They strike. Some of her works, particularly the paintings, might even déjà vu you with her mimicry.

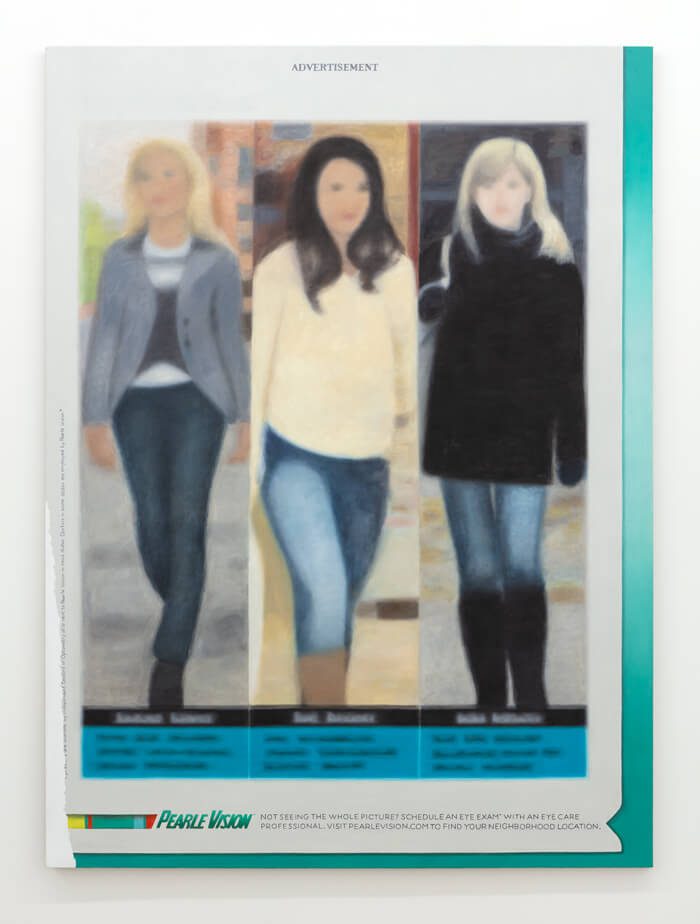

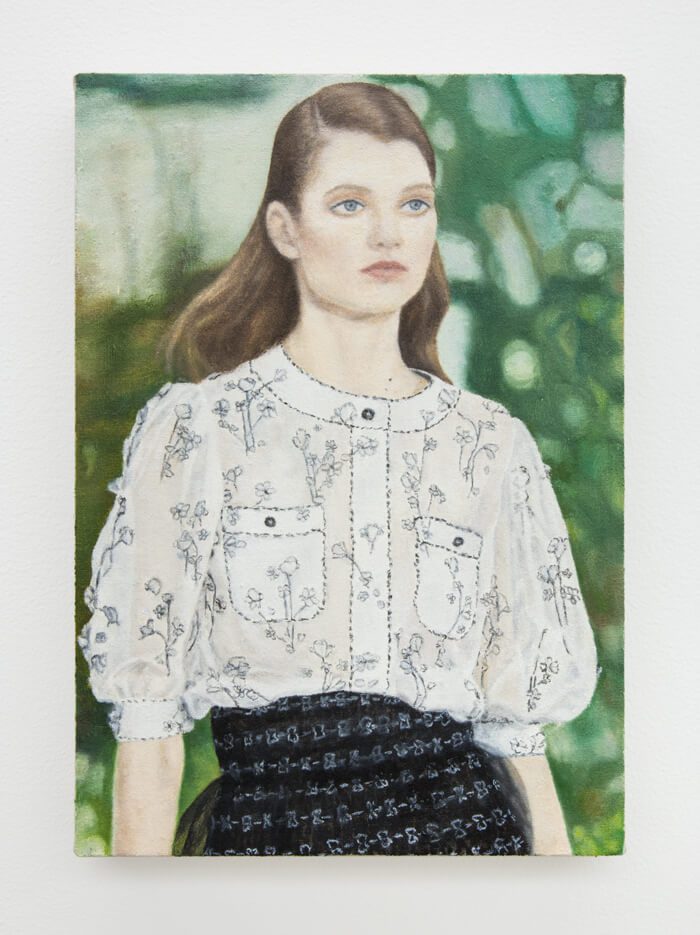

Following a deeper examination, there’s something left-field about the context. For instance: why does the woman who has been modeled from a recent fashion show seem to be sashaying out of a French Impressionist painting? How come Rawlings’s painted imitation ad for an optometry chain store—one that might be found in a magazine or blown up to poster size and displayed inside of a clinic—is extra gorgeous yet selectively focused? What can we ascertain in the blurred unseen, and what might our reaction to her purposefully placed psych-out say about how we identify with and move through the world?

“I’m always trying to play with explorations of beauty and what that means. I like to make things that are engaging visually, but in a way that almost feels unfamiliar, not quite as warm or as easy as you might think, or that there’s another motive behind it,” says Rawlings about her strategy of presenting common images in strange, unforeseen contexts.

There’s also cold awkwardness to some of the pieces, especially when one of her works is hanging in a staid gallery environment and projecting a sheen of discomfort.

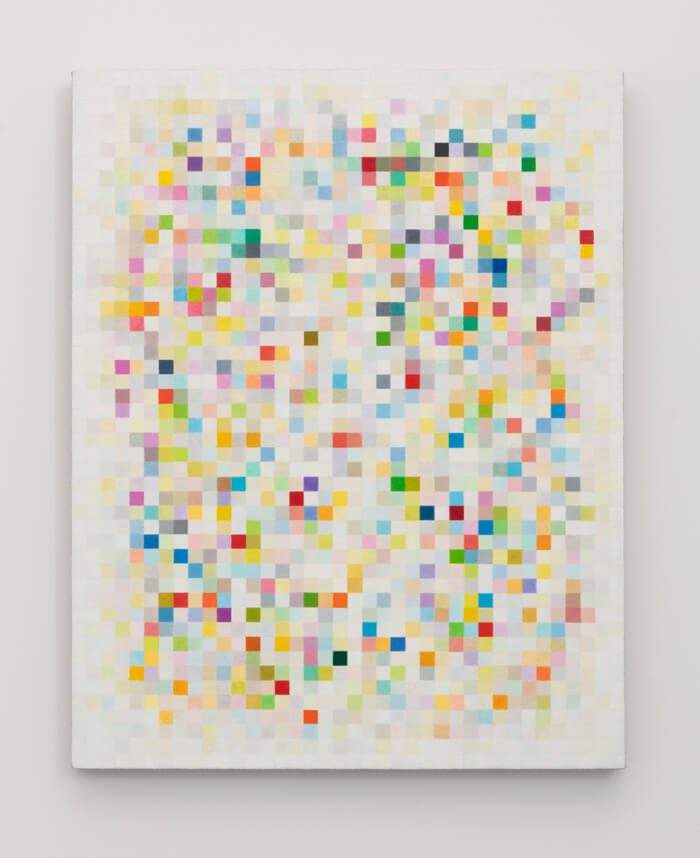

The artist—who has exhibited overseas in Warsaw, Tokyo, and Basel, and stateside in Los Angeles, Chicago, and her hometown Dallas—is unequivocally dedicated to, even unwavering about, her art practice. In addition to portraits, her work includes abstractions, sculptural works, monochromatic paintings, digital collages, and a series influenced by 20th-century grid paintings and embroidery.

What can we ascertain in the blurred unseen, and what might our reaction to her purposefully placed psych-out say about how we identify with and move through the world?

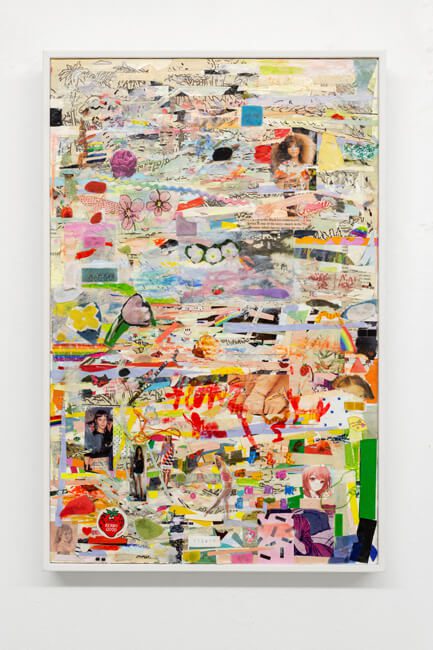

Her bulldog vigor comes through in works that explore image culture, whether they comment on the construction and evolution of individual psyche from adolescence to adulthood or evoke the entertaining yet helpless feeling of scrolling through online visuals. Her paintings conjure a strange and beguiling infighting of warmth and detachment without feeling off-putting or cynical.

If Rawlings had to summarize her approach to art and her overall life philosophy, it might be personified in one of her favorite quotes from the late Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges: “It’s enough that if I am rich in anything, it is in perplexities rather than in certainties.”

“It’s the sense that as soon as you are interested in or starting to zero in on one thing, a new bottom opens up and there’s an infinite number of new problems,” says Rawlings, who earned a master of fine arts from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2012 and currently lives in a live-work studio in Tesuque, New Mexico. “And I think that’s reflected in reality from a scientific perspective where the deeper you go, the more uncertain things become. The sense that our material world is static or certain is also problematized.”

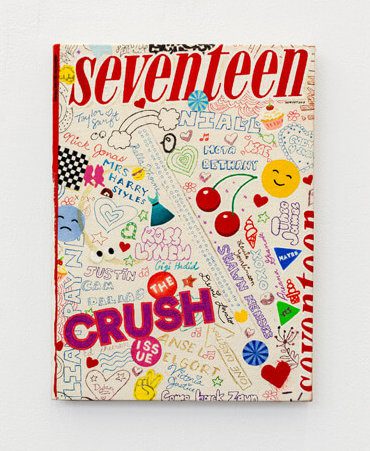

As a kid growing up in north Texas, Rawlings created her own folios from pages she clipped from fashion magazines. She was interested in how re-editing and recombining images changes their context—and thus their meaning—and how images become tropes that repeat themselves again and again. The offbeat compositions she fabricated from the rehearsed world of fashion advertising can often be found in her professional portraiture work.

“The models felt like stand-ins for the type of person that belongs in that kind of image. Similarly, with a lot of European painting of the last few centuries, it can feel like the models for the artists did more or less the same thing, even if they were part of the artist’s family or a personal friend,” Rawlings says. “I’ve always been interested in portraiture as a carrier of cultural signifiers and exploration of identity within cultural context.”

In high school, she discovered that she and her classmates could all perform the same assignment yet so many differences appeared in each artwork, even if all the students copied a painting or drawing.

“It felt like inevitably there is no real way to ever copy something in art, or do the same thing exactly the same way as someone else does. There are just too many variables,” says Rawlings. “You see that in the work of [Elaine] Sturtevant. Everything matters. Context matters. There’s a real freedom because it’s enough that it’s yours, even if you’re anonymously escaping into the work and it’s not supposed to be about you. It’s supposed to be about the world around you. It’s still yours and you can’t really escape that and that’s a beautiful thing.”

Her fascination with and deconstruction/reconstruction of image culture were most recently displayed during In the Garden, a 2020 solo show at Los Angeles’s Night Gallery. Rawlings sourced images from Virginie Viard’s spring 2020 haute couture collection for Chanel at Paris’s Grand Palais. Rawlings noticed that the fashion was an unabashed ode to French Impressionism and reimagined the figures as late-19th century women in full-body, waist-up, and uncomfortably cropped portraits.

“I’ve always been interested in trying to let the pieces speak for themselves simply as kinds of images we’ve seen before. I think a lot about how the seemingly benign environment we grow up in and the influences around us really do shape us, so to me that benign quality almost feels more ominous,” says Rawlings.

Along with awkward experimentation, another throughline in Rawlings’s work is capturing the sense of memory and all of its inherent mistakes. In a 2018 show at And Now, her second solo exhibition at the Dallas gallery, she displayed takes on visual culture perpetuated by new-age spirituality, the self-help industry, and doctor’s offices.

One of her larger wall pieces, entitled Pearle Vision, depicts a selective-depth of field painting of three women, all well-dressed in casual fab fashions in an ad for the eponymous eye-care conglomerate. The women, who aren’t wearing glasses, seem out of place. The left side of the piece looks as it had been physically torn from a print magazine. At the bottom, part of the clear text reads: “NOT SEEING THE WHOLE PICTURE? SCHEDULE AN EYE EXAM* WITH AN EYE CARE PROFESSIONAL.”

The piece is bewildering for its straight-forward presentation paired with an approach that’s half-a-click off-center. Do eye care ads really look like this or are we filling in the cracks in our memories with convenient (and potentially inaccurate) truths? Here, and in many of Rawlings’s works, our recall for and association with everyday images—which unconsciously whizz by on a daily basis—are directly confronted and questioned.

“This feeling extends with the internet where advertising and consumerism and personal life have merged. How do you choose who to be?”

“I hesitate to say nostalgia because I think nostalgia is a style. I’m actually more interested in the problems of memory and the ambivalence around and the gaps in memory. It’s more about ruptures and mystery and what we really can’t grasp or understand,” says Rawlings. “I’m really drawn to art, music, and film that’s very cold and even futuristic and presents a view of the world that’s severe, because that tends to be the least ironic kind of experience and something that still feels truly romantic.”

Rawlings explains that a feeling of fundamental uncertainty has festered in her since she started looking through magazines as a youth. Specifically, the choice of what to make as an artist, and being unable or unwilling to commit to a singular point of view, which “mimics the way reality is presented to us within media,” says Rawlings.

“Particularly as I experienced fashion magazines as a young girl, where an editorial about an escape to an obscure destination seems just as accessible a reality as images of street fashion in New York,” she says. “It’s all presented as possible consumer choices, and thus possible ways of being and even choices of identity. But none of these realities can really merge, so all of this choice and possibility becomes a very heavy feeling. I think about how at this moment the history of art seems that way, too… our past stays with us, a history of seemingly equal, accessible ways to express oneself.

“I think this feeling extends with the internet where advertising and consumerism and personal life have merged. How do you choose who to be? How do you choose your aesthetic and the life you want to live? What do you want your interiors to look like? What’s the mood you’re going for? What are you ‘channeling?’ What do you want your clothes to look like? Consumer choices become almost existential. Obviously, we’re all limited but even within those limitations, there are these persistent questions.

“And then of course there are ethical consumer questions. Do you buy vegan? Are you trying to buy local? Are you trying to limit your carbon footprint? There is a dizzying array of ways we can think about how to be in the world and what identities we want to embody,” continues Rawlings. “You feel like if you live by default you’re sort of disappearing. You’re missing out on an opportunity to create something interesting or be something interesting. There’s anxiety in that. And then if you do decide that you want to commit to something specific, maybe you’re missing out on other, better choices.”

Rawlings, who moved to Santa Fe in 2019, recently showed a new body of abstracted works at And Now in Dallas. It wasn’t her first foray into displaying abstract painting or genres outside of portraiture. In 2015, she exhibited paintings based on digitally-sourced visuals at Warsaw’s Raster Gallery. She also installed a life-size doll—currently on display in a group show at the Warehouse in Dallas—that’s a replica of Rawlings as a grade-school student, complete with her actual binders, homework assignments, and artwork.

In other words, a deep dive into Rawlings’s catalogue runs parallel to Borgesian perplexities rather than certainties, making it impossible to slap a pigeonholed genre or style on the always-evolving artist who couples familiar and sentimental visuals with gauche and iconoclastic orchestrations.

“A goal of mine is to be completely as far out on a limb as I can possibly be,” Rawlings says.