May Stevens’s retrospective at SITE Santa Fe showcases a selection of her politically charged yet personal paintings and prints that display her ability to embody her conviction in a variety of styles and themes.

March 26–June 9, 2021

SITE Santa Fe

“Just earning a living, not living a mental life, and not trying to change things was a life that was frightening to me. You become human only when you make this great struggle for realizing your life and making it count.”

—May Stevens (1924-2019), quoted in her New York Times obituary.

May Stevens’s retrospective at SITE Santa Fe showcases a selection of her politically charged yet personal paintings and prints. The show, which includes work spanning from 1963 to 2008, displays her ability to embody her conviction in a variety of styles and themes. From painterly realism to abstracted landscapes, her subjects ranged from images of her mother and father, women artists, death squads, freedom riders, and enigmatic boats adrift on the ocean surrounded by a literal handwritten “sea of words.” For every shift of style, cause, and subject, Stevens was all-in and wholly committed. There’s nothing half-hearted about her.

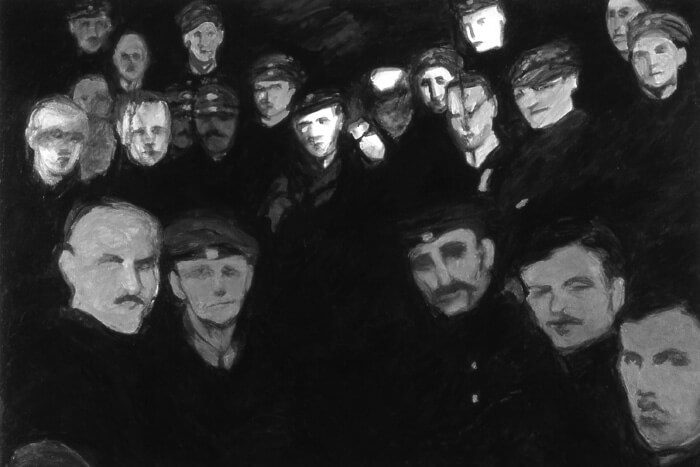

She depicted her mother and father in entirely different ways. In Forming the Fifth International (1986), her mother—in the throes of Alzheimer’s—is lovingly rendered with almost photorealistic brushstrokes in a green space, her legs and hands distorted and thrust towards the viewer. She twists to the other person in the painting, the Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, who Stevens considered her spiritual mother, painted in grayscale and facing the viewer directly.

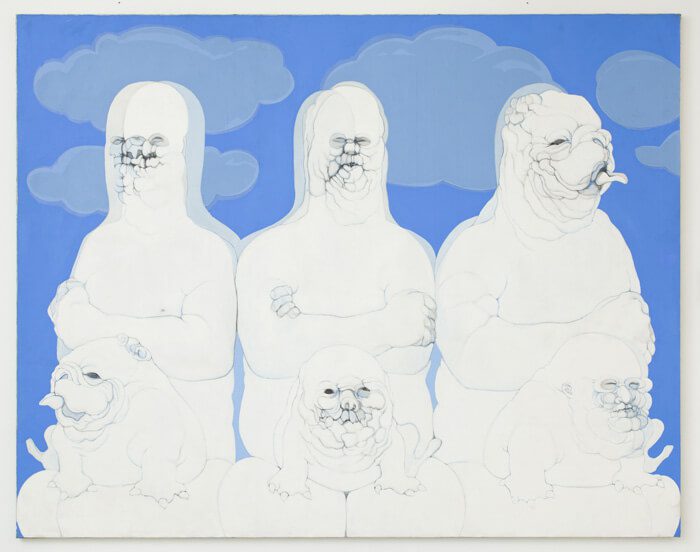

On the other hand, a decade earlier, in her Big Daddy series, Stevens mocks her father, who she saw as a racist, sexist bully, a symbol of the worst of America. In the three works presented here, she draws him naked with witty, playful lines; in Metamorphosis (1973), she depicts him exchanging his shape in three stages, into the bulldog on his lap and vice versa, fusing humor and anger.

Stevens, along with exhibition co-curator Lucy Lippard, was a founding member of the Heresies Collective, which published a feminist magazine on art and politics. All twenty-seven of the issues of Heresies are also on view.

Steven’s strongest work seems to have been made in her fifties, sixties, and seventies, possibly because a woman’s life trajectory is different than usually conceived. Stevens was able to break away from her oppressive background to create a remarkable degree of internal freedom through art, as evidenced by her enormous range of work over decades.