Margaret Neumann’s paintings are rooted in the human experience as it is translated through time, through the body, and through our many coping mechanisms.

No matter where you are

you are alone

and in danger—well

to hell

with it.

—Lorine Niedecker

My therapist once asked me, “Could we talk about our relationship?” Confused, I asked, “Whose?” She said, “Yours and mine.” “Uh,” I said, “We don’t have a relationship.”

But we did—albeit one that was intensely one-sided and involved money exchanging hands. After four years of seeing her once a week, using her tissues, and wanting desperately to know what she was writing down in that damn notebook, what else could it be described as? The fact that I didn’t recognize that we were, indeed, in a kind of relationship with one another I’m sure electrified her therapist-neurons because it afforded another glimpse into my patterns and behaviors and definitions.

Her question unmoored me because it asked something new, and it brought me out of my past and into the room so fast I was left a little breathless. The kind of art I love often throws me, leaves me a little breathless. Margaret Neumann’s art throws me. And what I like most about it is how I feel while I’m in the air—boundless, present, maybe a little nervous, and connected to a familiar, dreamy mystery.

I don’t bring up my therapist merely to brag about my fragile human condition but because Neumann works as a therapist and has for decades. In fact, when I interviewed her for this article she said, “I’m everybody’s therapist. I look like an ear.” I’m not going to say that you can see her profession in her art or that her canvases drip with Freud (gross), saying those things would be inaccurate. The connection, like all worthwhile connections, is more nuanced. Whatever compels her to be of service, to alleviate human suffering in this particular therapeutic way, also activates her painting. Her work is open and generous even as it plumbs our very private moments.

Margaret Neumann has been painting in Colorado for five decades. Born in 1942 in New York, her family moved to Denver when she was a kid and she’s resided here more or less since. She studied painting at the University of Colorado Boulder and graduated with an MFA in 1969. She’s had solo shows at Boulder Museum of Contemporary Arts, the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, and, in 2018, a retrospective exhibition at RedLine in Denver. While in graduate school, she was a member of the Armory Group, a group of artists and friends that included Clark Richert, John Fudge, Dale Chisman, John De Andrea, George Woodman (father of photographer Francesca Woodman), and Joe Clower—Neumann was one of the only women. These artists each had very different styles but shared in a community-minded zeitgeist. Some of the Armory Group co-founded Drop City, the famous artist community in southern Colorado; later they helped create the artist cooperative Criss-Cross. And others, like Neumann, went on to found Denver’s oldest co-op art gallery, Spark, in 1979. Spark, now located on Santa Fe Drive, was first housed in a former Italian grocery store in north Denver. The creative act woven into real life: the grocery store becomes the gallery, the gallery a grocery store. “Being a therapist is an art form,” Neumann tells me.

This is a recurring theme in Neumann’s work: grasping for something that isn’t there, searching for something that just dropped to the floor. There is an uncanniness in this kind of loss.

Neumann’s paintings are rooted in the human experience. But the experience as it is translated through time, through the body, and through our many coping mechanisms—one of which is humor. “Humor lets you out of yourself to see yourself,” she says. She tells me that she comes from a very funny family. “They were all hilarious, all of them. Not the best parents, but very funny,” she says.

In Voyage Long Time Ago, a human figure stands with their back to us. They are suffering from a head wound. The back of their head is bleeding, and a disembodied arm reaches into the frame, attempting to staunch the blood with their hand. But the attempt is futile; the wound keeps bleeding. Both the arm and the figure are painted in reds and the background is painted in whites. The colors are as minimal as the story. The relationship is stripped of its details. The details don’t matter here. It doesn’t matter if the two figures are lovers or family or friends or combatants, or a therapist and her client. What matters is one human being is suffering and one is endeavoring, and failing, to provide comfort. This is the deep tragedy of human connection. Empathy has its limits while our vulnerability has none.

This painting kills me. But here’s the joke: Living kills me. What is funny in Neumann’s work is the ridiculousness of the existential conundrum. It’s a kind of humor-at-our-own-expense. Neumann tells me that her father barely escaped the Holocaust, which killed nearly two-thirds of her family. Against that ancestral background of horrific loss and trauma, she describes a very difficult childhood, one that might be more akin to surviving than to growing up. She tells me, “I look at some of the shit that happened to me, and if I look at it from a distance, it’s ridiculous. It’s just ridiculous.”

I wonder if describing art is like explaining a joke. Once you explain it, it isn’t funny anymore.

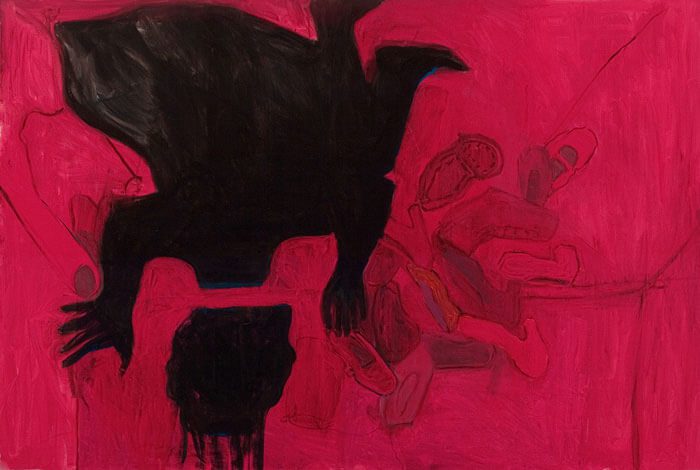

Goya and Me is in the collection of the Kirkland Museum of Fine & Decorative Art. The Museum categorizes its style on their website as “Referential Abstraction,” and defines that term as “art that abstracts something but the viewer can still tell what it is.” I feel like this could define anything between photo-realism and a doodle. The more I think about that categorization, the more I am tickled by the fact that it is so vague it could literally refer to anything. It’s endearing to me—our quaint, little, human need for categories.

What is funny in Neumann’s work is the ridiculousness of the existential conundrum. It’s a kind of humor-at-our-own-expense.

Definitions are interesting in part because they shift and change. Like perspectives, like emotions, like feelings. As far as Goya and Me is concerned, I suppose I can “tell what it is,” an upside-down human figure, cleanly and clearly beheaded, though only slightly (being slightly beheaded is kind of like being slightly pregnant)—the head floats just an inch below the neck. It is actually more like the neck was deleted. The figure is painted in blacks, crouching to fit inside of the frame. The figure floats in what appears to be a red room among other floating shapes reminiscent of human body parts. And, not to be too coy, but yes, I can tell what the painting is, it is a referential abstraction where the referent is itself an abstraction. Because it’s a feeling. The painting is the feeling of a hand desperately grasping for something that isn’t there.

This is a recurring theme in Neumann’s work: grasping for something that isn’t there, searching for something that just dropped to the floor. There is an uncanniness in this kind of loss. It feels like stepping off a curb in a dream but never touching the street. You jolt awake just before you plant your foot—the electricity of adrenaline coursing through you. My mother looked at Neumann’s paintings and told me, “They look like dreams watching dreams.” Neumann said, “I think your mother’s description is a pretty good description…[a] person’s life is much more internal than what we witness. And I think my paintings are about my feelings and of feeling lost and very alone and alone in the universe and not knowing what the universe is. And I don’t know where to hold onto things.”

In Cherries she paints a clump of cherries viewed from above. But, where are these cherries? What universe are they in? They hover in a rectangle of dark matter, weightless for no reason I can decipher. Have I ever seen cherries from the top like this? Am I a drone? If so, why am I spying on cherries? Are these in fact cherries, or are they tops or pinwheels? The cherries aren’t appetizing. Their stems are too prominent, foregrounded, in a tangle, they are a barrier between me and the sweet fruit. I love how important the stems become here; I love how I begin to think about things we cast away. Might the stems be more meaningful than I ever gave them credit for? Do they hide a symbolism I’m missing? I wager in my head that Margaret Neumann is the kind of woman who can tie a knot in a cherry stem with her tongue. So I ask her.

She’s never even tried.

“But that’s the kind of person I am. I just like the cherry. To hell with the rest of it. You deal with the rest of it.”

Rule Gallery will present a solo exhibition of new work by Margaret Neumann in the spring of 2021.