April 8 – June 10, 2017

No Land, Santa Fe

There is one segment in the episodic Bayeux Tapestry—the famous 230-foot long textile (ca. 1070-1080) that depicts the Battle of Hastings in 1066—where the English King Harald is celebrating his ascension to the throne; nearby a group of men point to the sky in wonder. They are witnessing what to them is an auspicious celestial sign that bodes well for the new King: Halley’s Comet flashing by in its cyclic journey. Even rendered in crude embroidery, there is no mistaking the stylized comet up at the top edge of the textile. Humans have been gazing and pointing and recording their astral observations for many thousands of years. And the art of sky watching since the Renaissance has flourished, refined its focus, and given birth to data both purely scientific and that which has been merged evocatively with the visions of artists who have juiced up the data by way of poetic license, transforming the spaces and the objects they observe, bending them to their will.

In Marcus Zúñiga’s multifaceted and deeply absorbing exhibition Ya Veo (I See) (April 8-June 10, 2017), there are eight separate pieces that comprise work such as digital video, a small LED installation, Mylar and thread on paper, and an acrylic sculpture which takes a fair amount of scrutiny to fully understand all the parts to the whole. In this work El Imán (The Magnet), unless looked at carefully, it would be easy to miss the slender wires inside the structure with their delicate iron filings standing at attention as the accompanying magnets exert their polarizing force. Zúñiga is part scientist and part conceptual artist, and as small as the rooms are in No Land gallery, never once did I feel that any given piece in Ya Veo did not find an adequate spatial matrix in which to glow, pulse, mystify the viewer, or move across an implied vastness in order to complete an arc of visual and metaphysical meaning. Zúñiga’s work is economical, elegant, and long on mesmerizing properties.

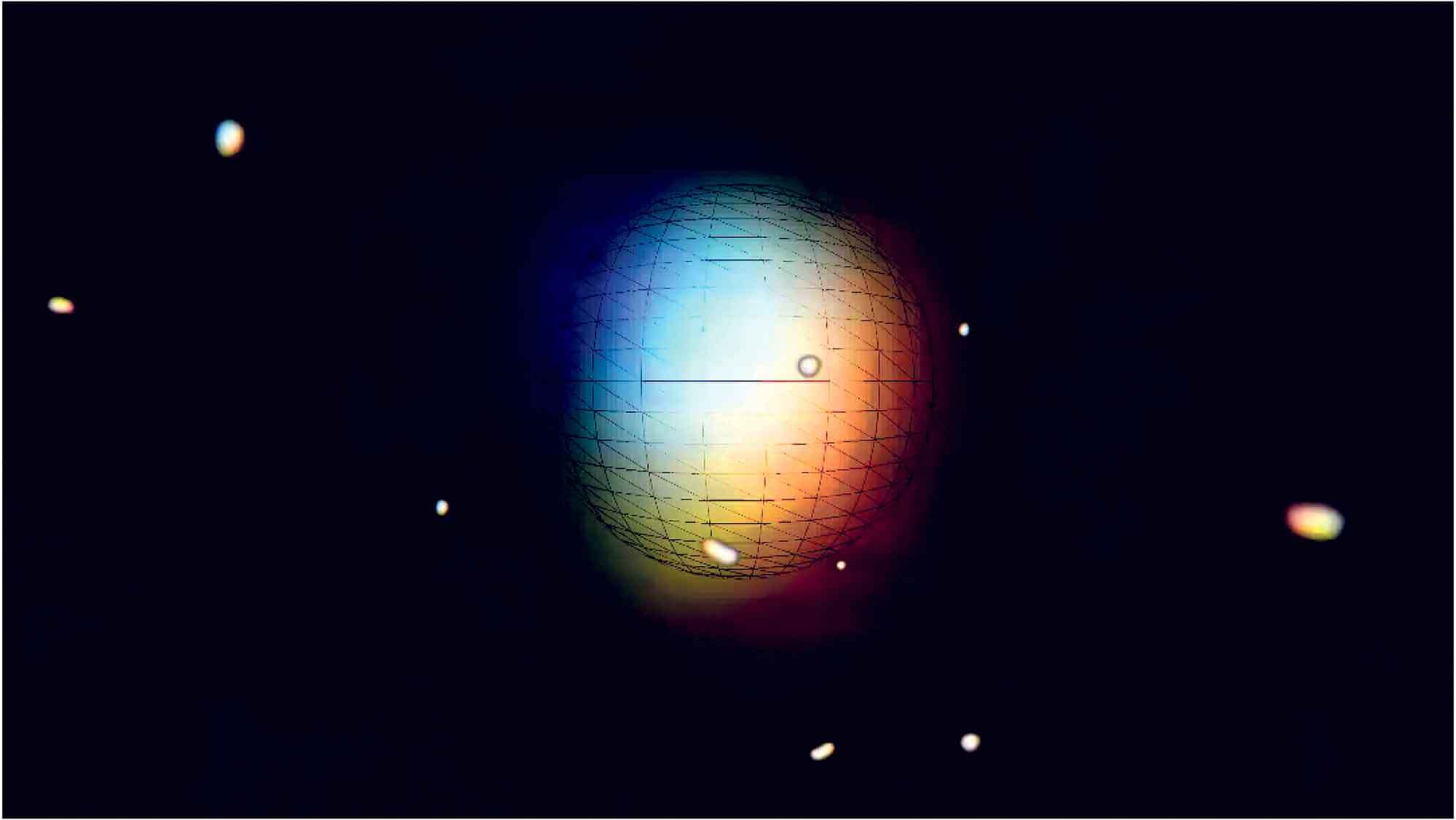

This hypnotic quality is especially evident in the two video projects, Eclipse Total (2017) and Hidrógeno/Helio (2016). In the former piece, Zúñiga recorded through his telescope both lunar and solar eclipses and manipulated their halating effects so that one eclipse blends effortlessly with the other. The artist has choreographed the material into a sequence of graceful movements of moon and sun so they appear like dancing bodies sweeping up, down, and across the wall in an extraordinary pas de deux: the moon moves down, the sun moves up, and the two forms then glide toward each other, meeting in an eclipse which then generates the feeling of an almost heartbreaking loss. Then the cycle is continued, but the sun now sinks downward and the moon ascends. This dance could be likened to an attenuated series of parabolic curves that never seem to repeat, but of course they do. For eight minutes and twenty-six seconds, the observer is consumed by the observation, and the magical realism inherent in Zúñiga’s art comes to fruition in a closely watched dance of affinities.

The artist has choreographed the material into a sequence of graceful movements of moon and sun so they appear like dancing bodies sweeping up, down, and across the wall in an extraordinary pas de deux.

In the mathematics of the parabola, there is something called an “affine transformation,” where parabolic curves preserve parallel relationships in something called affine spaces, and the mapping of these mathematical relationships is called a “translation,” which on an intuitive level is exactly what Zúñiga has done through his affinity with the night sky and its artistic bigger picture of metaphorical space, time, matter, and movement. His vector mappings of celestial bodies and the light that comes from various constellations is beyond the merely awe inspiring. Rigorous in his recording and the transformation of his observable facts—and supremely insightful in his fusions of art and science—Zúñiga has not lost sight of humanity’s place in the sweep of the cosmos as he delicately balances his parables of the near and the far. For Zúñiga, the increments of his awareness will be the differentials of his evolution as an artist.