Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque

February 3 – May 6, 2018

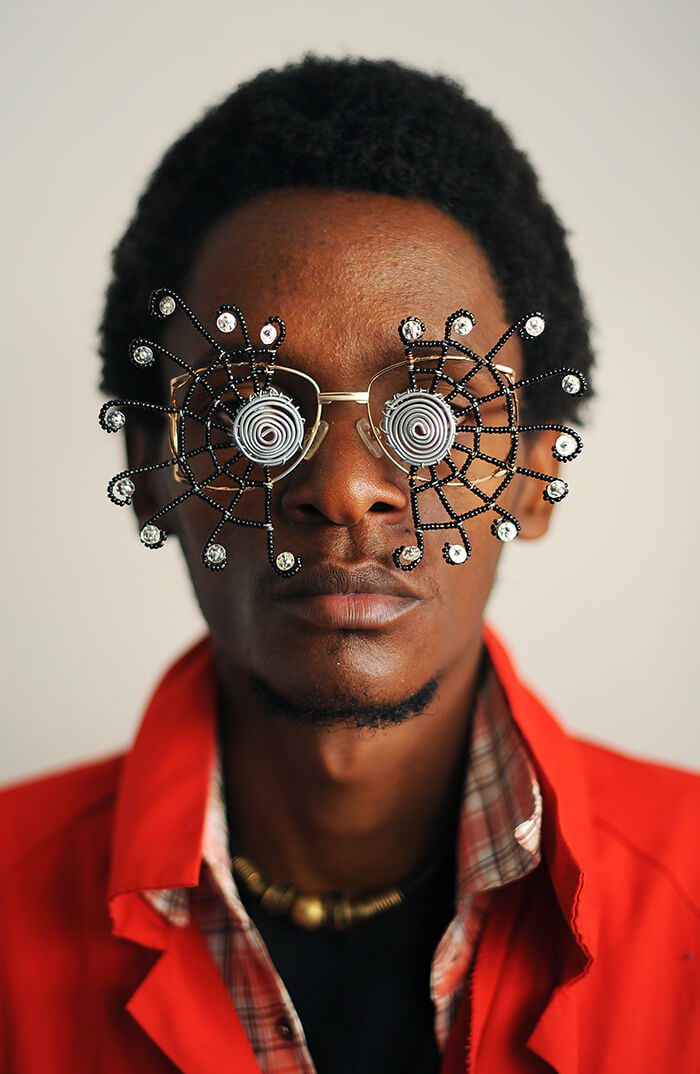

Open your eyes. Videos looping in the background ask us to do that just as the cluster of sculptures on wire display mounts in the center of the room present us with that enlightening concept made manifest. Eurocentric narratives hugely impact global perceptions of what Africa is, what ideas and art the continent embodies and exports. Stereotypes, by design, can’t encompass the multiplicity of stories that, taken as a whole, represent the truth. Surrounding Kenyan artist Cyrus Kabiru’s wearable eye sculptures, video screens transmit the words of thinkers, curators, and creatives on the new concepts and authentic, inclusive tropes that more completely approach the questions: What is Africa? What is African design?

Kabiru’s work, flanked by the screens, is a metaphorical eye-opener, welcoming visitors to Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design at the Albuquerque Museum, an exhibition developed by the Vitra Design Museum in Germany and Spain’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. The multiple works, called C-Stunners, are made of upcycled wire, tin, screws, and cork; they fit over the eyes, having the effect of bits of futuristic cyberpunk costumery, though they are culled together from discarded objects. They illuminate multiple themes that run through the massive exhibition—the clear enunciation of new narratives that upend colonial ones, the intersections of innovative design and ordinary materials, and the particular works that shape a broader, diverse landscape.

The exhibition necessarily speaks to the singular, with an eye on a bigger, more complex whole. To approach the design of a continent that encompasses fifty-four countries, more than two thousand languages, a billion people, and myriad distinct cultures is mightily ambitious. Rightfully, that makes the exhibition sprawling. More than 152 artworks by about 120 different artists are arranged throughout multiple, beautifully staged galleries. There are four sections: a Prologue, “I and We,” “Space and Object,” and “Origin and Future.” Within these, we have video games streaming on eye-level television screens, hip-jutting mannequins showing off forward-looking fashion, inspired furniture, photography, vividly designed websites, music videos, stills of graffiti, documentation of dance, and more.

Each section tackles different elements of African design: confronting stereotypes, grappling with history, the creative explosion in urban centers, and how the creative sector allows for self-definition and far-reaching, even world-shaping, expression. Here, the exhibition posits, are the seeds that are already shaping—and will continue to shape—the global future of design.

Works like the website of pop singer Taali M virtually jump right off their mounts. The site, designed by artist Pierre-Christopher Gam for the French singer of Congolese, Chadian, and Egyptian descent, is meant to transport the viewer to a lost African kingdom. The infinity of shapes, the moving images of Taali M expanding and receding across the page, hypnotize and, yes, transport the looker to a vibrant otherworld very much apart from the dim gallery. This is an example of the spot-on curation; the inclusion of things like web design underlines the show’s relevance and makes it unselfconsciously cool.

Others, like Ponte City, by photographers Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse, also transport us, but to a different reality. Their piece is a study of a Johannesburg apartment complex, fifty-four stories high, that was once known for its luxury. In post-apartheid decline, the complex became increasingly run down. Across three twelve-foot lightboxes that mimic the reach of the towers themselves, they have arranged—in an exact order—photographs of every television screen, doorway, and window of the homes tucked inside of Africa’s tallest apartment building. Viewers are privy to individual lives that play out across the vast grid—again, the multiplicity of particular stories that thread through the

bigger ones.

The exhibition taken as a whole—as massive and diverse it is—has the effect of transporting visitors as they wander the wing of the museum that holds the exhibition’s sprawl. If there is any guide for the expanse of Making Africa, it comes in literal maps like Kai Krause’s The True Size of Africa, and Nikolaj Cyon’s Alkebu-Lan 1260 AH, two figurative plans that create an intellectual avenue toward a fuller understanding of the exhibition and the place. Krause’s map is a counter narrative to the skewed Mercator projections of the world, illustrating how the continent of Africa can swallow North America, China, and most of Europe. It underscores the impossibility of a truly comprehensive exhibition on the design of Africa but also speaks to the importance of reevaluating the prevailing narratives of the place, just as Alkebu-Lan 1260 AH does. Cyon’s map, born of years of historical and artistic research, is a rewriting of history, a topographic representation of the political terrain of Africa had it never been colonized.

A final station of Making Africa invites visitors to sit down and scroll through a series of videos by African intellectuals. I used the touchscreen to cue up a TED Talk given by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. She discussed that as a child she wrote stories about snow and eating apples, because that’s what children did in the books she was reading, all published in Europe. Accessing African books changed her world and her art. She notes how “impressionable and vulnerable we are in the face of a story,” which brings home the importance of the innumerable ones told in Making Africa. Here are vital counter narratives to the toxic flattened

stories that too often prevail. Making Africa, in its multitudes, works in many ways: it is education, inspiration, and antidote.