Harwood Museum of Art, Taos

May 22 to September 11, 2016

Albuquerque Museum, Albuquerque

October 29 – January 22, 2017

When I think of Mabel Dodge Luhan and her company, celestial analogies spring to mind: a constellation of disparate personalities, a system of spinning bodies suspended and connected, held in balance by the gravitational force of a central figure whose brilliance is both perilous and life-giving.

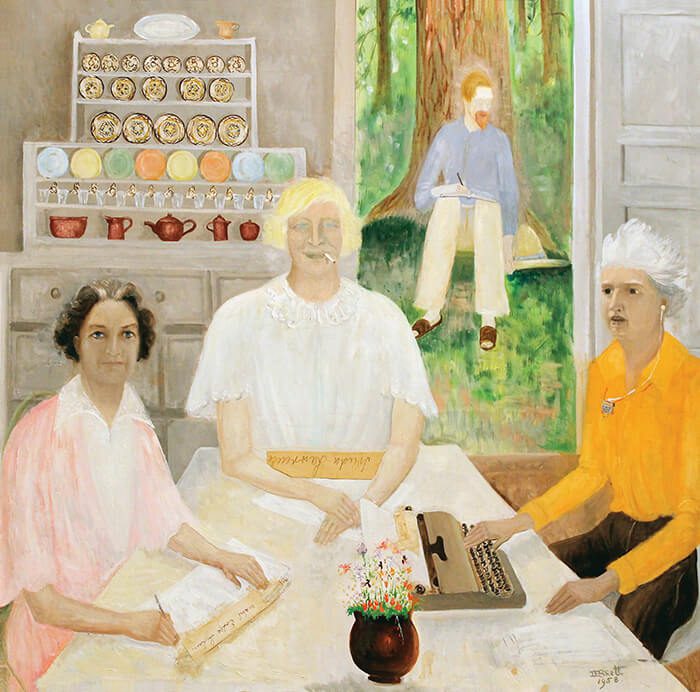

Mabel Dodge Luhan, the arts patroness who made New Mexico her home from late 1917 until her death in 1962, is noted for supporting some of the foremost creatives of the early twentieth century. Following successful salons in Florence and New York City, Mabel planted herself in Taos and entertained many of the best known figures of Modernism at her sprawling adobe estate, Los Gallos. Georgia O’Keeffe, Andrew Dasburg, Willa Cather, and D.H. Lawrence all came to New Mexico at her invitation.

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company: American Moderns and the West, co-curated by Dr. Lois Rudnick and MaLin Wilson-Powell, comprises decades of research to present Mabel’s impact on Modernism and specifically the development of Modernism in Taos. The exhibition, which was at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos from May 22 to September 11, will reopen at the Albuquerque Museum on October 29. For those of us fortunate enough to visit both museums, this is an exciting opportunity to see how a traveling exhibition is translated from one venue to another. While the content remains essentially the same, each venue has a certain degree of creative license in its installation.

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company comprises over 170 items, including paintings, sculptures, and other ephemera to illustrate the breadth of Mabel’s circle. Along with paintings by more well-known artists, such as O’Keeffe, Dasburg, and Marsden Hartley, the comprehensive selection of artwork includes several unexpected highlights: a scintillating abstraction in rainbow colors that prophesies Emil Bisttram’s Transcendental period; two skillful pastel drawings and a compelling painting by Agnes Pelton; a vibrant watercolor of a herd of horses by Pop Chalee; a massive Death Cart by Patrociño Barela; and the only known extant painting by Frances Simpson Stevens, one of two American women to have exhibited with the Futurists in Italy.

Preparation for the exhibition also led to some exciting discoveries. Rudnick tracked down a belle époque portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche of Mabel dressed in lavish robes, which had been sitting in storage at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery since 1924. It was restored specifically for this exhibition. She also located a bronze bust by Maurice Sterne, Mabel’s third husband, that had been in the basement of the Chicago Art Institute for over seventy-five years. The bust depicts Pablo Mirabal, grandfather of Taos pueblo artist Jonathan Warm Day Coming, and is now part of the Harwood’s permanent collection. And Wilson-Powell happened upon Feather Dance, a Dorothy Brett painting that had not been exhibited since 1965, while doing research at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin.

One of the largest shows the Harwood has organized, Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company spanned the entire museum. On the ground floor, the exhibition was arranged chronologically, beginning with Mabel’s childhood in Buffalo and winding through her stints in Paris and New York before introducing the artists and writers she brought to Taos. Upstairs, sections were dedicated to Mabel’s collection of santos—and her questionable attitude toward Hispano artists—Taos Pueblo and her activism in support of the Pueblo, Pueblo easel paintings, and finally a brief overview of Mabel’s 1947 publication Taos and Its Artists.

I’m a bit of an exhibition label nerd, so when I visit an exhibition, I look not only at the art, but also at the labels and at how well these two elements work together to tell a compelling story. Ideally, labels should illuminate the artwork on view and reinforce one key concept that ties everything together. Label guru Beverly Serrell describes this as a “big idea” in her book Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach. In an impactful exhibition, the big idea guides all communication channels: design, layout, the selection of objects, and their labels. In Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company, most of the section labels (the larger labels that introduce a sub-section within an exhibition) featured a rundown of names and dates; many of the labels for individual objects likewise hinged on dates and occurrences rather than on the objects they were meant to elucidate.

This timeline-style narrative supplied basic information about Mabel’s life and interesting tidbits about her influence and relationships. However, Mabel herself––her thoughts, her intentions, her voice––was relatively absent, and the information provided did not present a particularly nuanced view of her or her appeal. Mabel had, and continues to have, a reputation for being forward, meddling, overbearing, and man-obsessed––I overheard comments from fellow visitors at the Harwood confirming as much––but she was also charismatic and had a knack for making people feel heard. Facilitation is an art in itself, and Mabel was, by several accounts, a master. Her ability to attract, gather, and encourage people was perhaps her most important trait. Without it, there may have been no “company” to speak of. And yet, this skill is only mentioned in passing, on a label with a reproduced image of a charming portrait of Mabel that presents her as poised, attentive, and approachable. As the label points out: “In her Portrait of Mabel Dodge, Mary Foote painted Mabel as a warm, lively, and receptive listener, posed as if she is forever leaning forward to listen to the wild and diverse mélange that filled her living room.”

I left the Harwood feeling delighted by the fascinating array of artwork but without a clear takeaway. I also felt as if I’d been to a fabulous party and missed the guest of honor. Or, in Mabel’s case, the hostess.

At the Albuquerque Museum, the labels and much of the artwork will reappear in the museum’s North Gallery, but there will be some notable differences. At the time of this writing, the exhibition was still in crates, but Curator of Art Andrew Connors thoroughly “walked” me through the museum’s plans for it. Foremost among the changes is a reconfiguration of the exhibition layout to communicate key concepts. For example, the exhibition will open with a comparison: relatively traditional paintings by the Taos Society of Artists, who were in Taos before Mabel arrived, will hang next to work by Mabel’s Modernists to illustrate her impact on the Taos art scene.

Her voice rings clear, revealing a complex woman whose controversies have overshadowed a remarkable sensitivity––a deeply observant “creator of creators” who found value and potential even in the everyday.

Other sections will be installed around the central space of the gallery to highlight the cross-cultural exchange that occurred in Taos during Mabel’s era. Work by Hispano artists will be exhibited with that of their Anglo contemporaries, and a glance across the gallery will remind viewers of work created by Taos Pueblo artists and Mabel’s Modernists.

Beyond the North Gallery, the Angelique + Jim Lowry Gallery will feature work by Taos Moderns selected from the museum’s collection by Assistant Curator of Art Titus O’Brien. While not part of the larger exhibition, these prints and drawings by artists such as Cady Wells, Kenneth Adams, Earl Stroh, Thomas Benrimo, and William Rowe will provide an extended view of Modernism in Taos.

Mabel Dodge Luhan & Company provides a long overdue look at Mabel’s influence and accomplishments. The selected artwork presents an impressive visual résumé. Rudnick and Wilson-Powell’s dedicated research, together with the organization of the exhibition around Mabel’s impact on the Taos art scene planned by the Albuquerque Museum will, I think, provide a clear sense of the creative and cultural exchange Mabel fostered in Taos.

But, before you go (or even after), pick up one of the memoirs Mabel authored in New Mexico, Edge of Taos Desert or Winter in Taos. Get to know the force behind it all from the land that changed her life. Her voice rings clear, revealing a complex woman whose controversies have overshadowed a remarkable sensitivity––a deeply observant “creator of creators” who found value and potential even in the everyday.