In Luis Jiménez: Motion and Emotion at Albuquerque Museum of Art and Art History, Jiménez is understood as an individual who insisted on bringing his own experience and his culture into the mainstream of art.

January 16, 2021-ongoing

Albuquerque Museum of Art and Art History, Albuquerque

A couple of doors down from the big Frida Kahlo-Diego Rivera exhibition at the Albuquerque Museum, in a tiny gallery, is a small but exuberant show of Luis Jiménez’s prints and drawings. Jiménez, who was born in Texas in 1940 and lived in New Mexico until his death in 2006, was a prolific public art sculptor whose work stands all over the Southwest and in front of the Smithsonian. In his work, he looked at the story of the American West through a Chicano perspective and added another facet, another lens through which to see it.

I admit that in the past, I have been on the fence about his sculptures. I thought of them as powerful but “lumpy.” His color palette, on occasion consisting of magenta, teal blue, and lemon yellow, makes my eyes water. Now, looking at the marvelous two-dimensional work in this current show of drawings, lithographs, and sketches for sculptures, I changed my mind. Jiménez was a tremendous draftsman. He drew with sweeping lines and without any niggling hesitation. His drawing manages to be swashbuckling, ironic, and sympathetic to its subjects all at once.

As you might expect of a sculptor, Jiménez had an aptitude for rendering bodies in motion and in space. In the 1981 colored pencil drawing SOD-BUSTERS (the title is written in a ’70s-style font across the bottom) of oxen pulling a plow, the gigantic beasts, bulging with muscles as if on steroids, look as if they might charge out of the paper, dragging the plow and the plowman behind them into the gallery room.

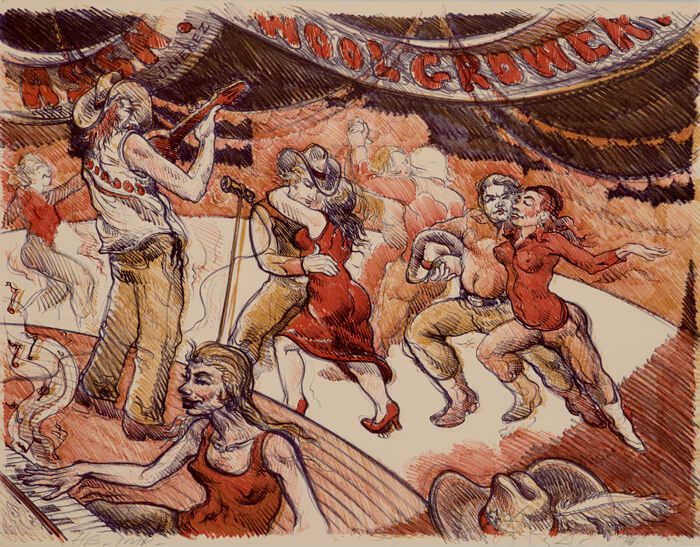

In the wonderfully affectionate lithograph Dance at the Wool Growers Association (1979), couples wriggle across the dance floor while a guitarist plays to the dancers. A female piano player in the foreground faces the viewer, her fingers flying over the keys. Departing from the artist’s normal palette, the lithograph is printed in layers of earth tones but jumps with vitality. It’s one of those pictures that activates the viewer’s other senses besides sight; of sound, of smell, of heat. Though Jiménez studied the great Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and especially José Clemente Orozco, this print reminds me of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters for French cabarets.

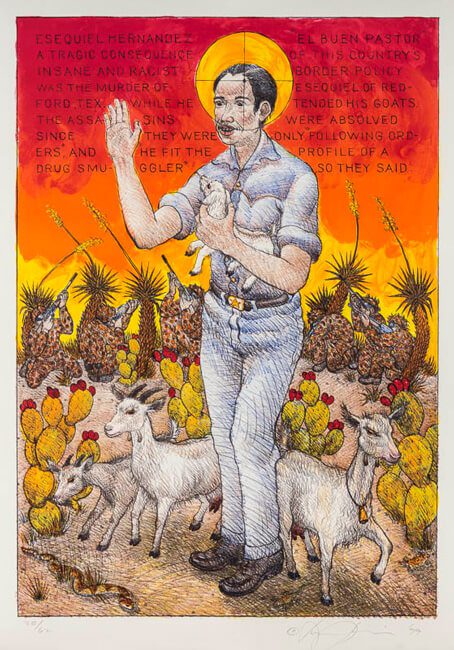

The most striking piece in the show is El Buen Pastor, a lithograph from 1999. The backstory—hand-written across the top of the print—is of an innocent shepherd shot by camouflaged U.S. agents who suffered no consequences for the murder. The frail young man, standing upright in faded jeans (shaped by relaxed, expert cross-hatching marks in blue) looks bemused; around his head is a gunsight that doubles as a halo. The sky behind him is a burning red color which gives the feeling of closing off all options except the inevitable. Meanwhile, at the shepherd’s feet, his young goats look around, alert, perhaps spying the agents in the back camouflaged as spiky cacti, bristling with guns. Of course, “the good shepherd” is another name for Jesus Christ. There is an odd quality to El Buen Pastor; it is tragic, doom-laden, and intentionally funny. Everything in it is ridiculous, except maybe the goats. Only a really good artist can make a viewer feel outraged at the tragedy of this man’s death and tickle their funny bone at the same time.

After seeing Luis Jiménez’s prints and drawings, I understand his sculptures differently. While I once thought they were theatrical, I now appreciate that they are authentic to the individual who made them, who insisted on bringing his own experience and his culture into the mainstream. Sometimes it feels good to be wrong.

No review of Jiménez’s work would be complete without mentioning his own tragic death. He died when a piece he was making for the Denver International Airport fell on him and severed an artery in his leg. You may see the sculpture, a large blue mustang, at the airport next time you pass through.