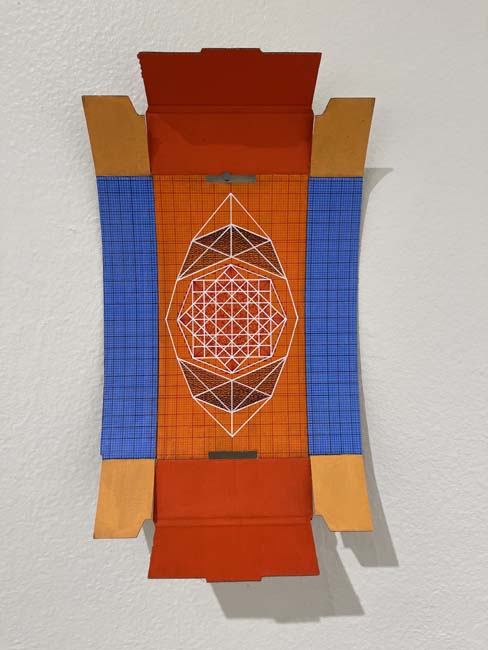

The centerpiece of Nima Nabavi: Visiting is the intricate geometry that he practices, letting the silent slide of his pens continue their daily run to infinity.

Nima Nabavi: Visiting

January 28–March 5, 2023

Roswell Museum

Visitors to Nima Nabavi’s exhibition, Visiting, at the Roswell Museum, aren’t just acting the title—some are on the floor, getting close, going in. This interaction isn’t surprising. The intricate geometry is eight miles deep. You want to get right down on it, hoping to see mile nine.

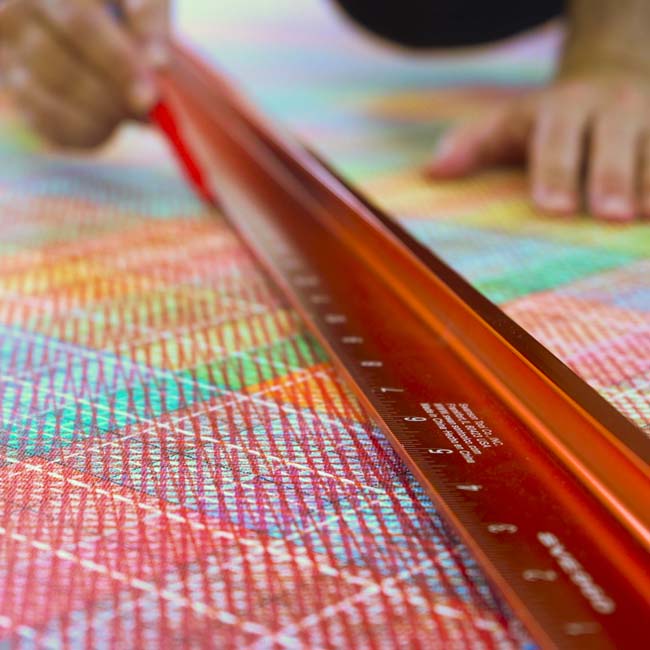

The six-by-eighteen-foot pen-on-canvas piece was created on the floor of Nabavi’s studio at the Roswell Artist-in-Residence compound and is likewise installed on the floor of the museum.

In addition to the main piece, the walls of the room are mounted with various forms of documentation of the project, one of which traces the paths of beetles and millipedes traversing the drawing—all generously welcomed by the artist—including the sun-seeking lizard that came daily.

The artist will continue to work on the piece in the museum, letting the silent slide of his pens continue their daily run to infinity, one pass at a time down the edge of his eight-foot ruler.

The work will go on until he prepares in March to leave for upstate New York, hopefully for a long nap in the Catskills—though, there the resemblance to Rip Van Winkle ends. Nabavi filled his residency with work—each day standing for every day, quite unlike Mr. Van Winkle, whose laziness made him famous. This artist, on the other hand, is known among those at the residency compound as a kind, steady, and helpful presence.

Born in Tehran the year before the Iranian Revolution, Nabavi grew up in the UAE and lived in the U.S. for a couple of decades before returning to live in Dubai in 2014 to begin in earnest his life as an artist.

That was a pivotal year for Nabavi in many ways: it was the year his entrepreneurial ventures in the U.S. came to a natural end; the year he first attended Burning Man; and, most importantly, the year his grandfather passed away.

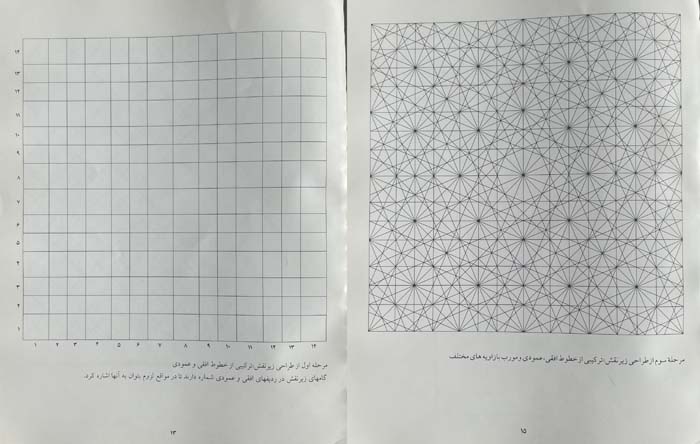

Hassan Shadravan, the man the artist knew as his grandfather, was a self-taught sign painter who retired in his fifties and became possessed of a desire to draw and redraw designs derived from grids, with an eye toward looking through them to some greater grid.

In the museum today, Nabavi recalled something he learned as a child—the proportions of 7 5 5 7 5 5 7 for assigning vertices to aid in the creation of a grid from which all manner of shapes, notably the hexagon, prominent in Islamic geometry, may be derived. It is a grid with a haiku for a mother and a palindrome for a father.

The hermetic nature of his grandfather’s pursuit was in contrast to the proliferation of Islamic geometric design, which is ubiquitous in Dubai in the form of packaging, advertising, and signage, to the point that it has become cultural wallpaper—very different than what Shadravan was chasing.

Somehow, through some mystery of atavism, almost as if something implanted had been activated through the mechanism of another’s passing, Shadravan’s commitment found itself in the hands of Nabavi. The grandfather’s hobby, always more serious than anyone had a way of realizing, finds its fulfillment in the art of the grandson.

To draw and redraw the same lines over and over shows faith in more than the translucence of the marks made by the pens—it is recognition that to retread the same path really is to see it for the first time. The build-up of lines is like the build-up of a life after another life. The point of contact, where Nabavi stands on Shavadran’s shoulders, is itself a vertex connecting the timelines of two lives.

It is fitting that the work is installed on the floor, offering as it does a way through to free fall. The center, as illuminated as any sacred manuscript could claim to be, is a crystalline portal accessible by surrender, or at least its glow is suggestive of the same.

Whether it’s the hint of a flight path or the inference of pleasing hallways, these “form constants”—cobwebs, lattices, checkerboards, honeycombs—structures that recur in quantum physics, the natural world, geometric art, and the spaces on offer by psychoactive plant medicines, invite you to climb on scaffoldings that support and cling to a structure that can only be apprehended quasi-fully in rare moments.

Electrochemical signals firing in the visual cortex; patterns observed by or caused by brain circuitry—indications of antennae potentially sharpened to perceive deep structures, snowballing fractals morphing into entoptic overlays, sparkling there because the human organism is the interface that connects to it. Basic elements like line, square, circle, star, triangle, ever-morphing polygons, tessellations—the brain is equipped to assume from these things insights about the nature of existence.

Nabavi knows that mastery of this field of knowledge and endeavor is not the point. He notes that people have deep responses to his work and is motivated to further that kind of connection. It is a loving relatedness, as is his process.

The stanchion and rope are there to remind you that this is a work for the public—it does not belong only to you, even if your inclination is to gaze into it, lay on it, fall through it. The sun-warm center beckons—so as long as you’re visiting, remember it, take it with you.