Peters Projects

December 16, 2016 – February 11, 2017

Is it possible for an artist to exhaust the format of the self-portrait? Or are we better off asking the opposite question: are artists’ reflections on their own likeness ever enough to fully describe depth of character, change over time, or one’s psyche? Kukuli Velarde compulsively and almost exclusively makes her own face and form the object of her art. We look at her and then her art only to realize they are one and the same. It is through this doubling that we come to confront the history of colonialism in Velarde’s native Peru. The self-portrait goes beyond likeness to become a profound survey of her own mixed-race body. Like many Latin Americans, she is the sum of indigenous and Spanish bloodlines, a veritable mix of oppressed and oppressor.

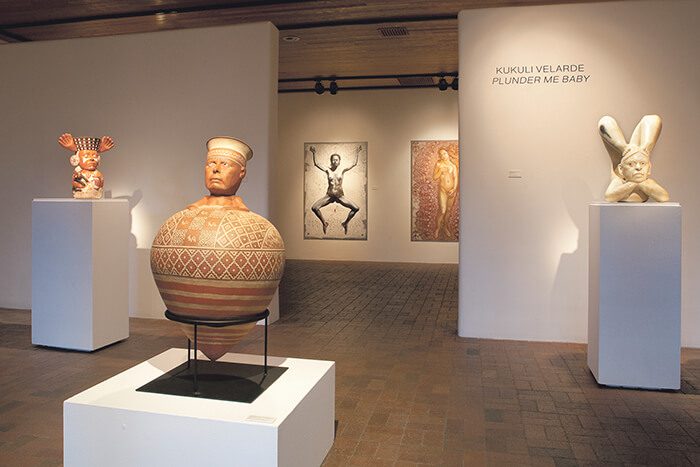

Peters Projects features Plunder Me Baby (December 16, 2016-February 11, 2017), curated by Mark Del Vecchio, a small showing of ceramics and paintings from the artist’s larger oeuvre. The title refers to a specific body of work, the Pre-Columbian-style ceramics dispersed among the first of two rooms. In the second, viewers encounter large Baroque-style portraits, replete with gold leaf and references to Catholic icons, as well as more contemporary and graphic meditations on the artist’s body. Peters Projects embraces both media under the banner of Plunder Me Baby, though the artist was quick to point out to me that the paintings come from other, earlier series (Corpus, for example, is about syncretism, or the survival of indigenous traditions through Christianity; the vibrant Cusqueña Baroque sensibility shows through in these works, painted on metal as opposed to canvas). While this might lend to some confusion, the difference between each body is clear upon a closer looking. When seen together, it’s possible to consider the connections across Velarde’s work, for, in many ways, the medium is the message: the two (opposing) genres, ceramics and painting, reference the before and after of conquest.

“I come from a country where racism is against ourselves,” Velarde said recently in her artist talk for the opening of the exhibition. Creating self-portraits gets at this sense of collective self-loathing, a gesture that makes her own body a site of identification and repulsion. In each example, “I had to use my face, otherwise it would be me talking about somebody else.” Plunder Me Baby speaks to this; not only does each bear her likeness, works’ titles bear racial slurs and insults typically directed at indigenous peoples in Peru. In India Patarrajada, Velarde gives us the side eye, her mouth slightly agape, squat legs contorted behind her head. Likewise, her bug-eyed gaze in Chola Puteadora practically sears anyone who crosses its path, reclining brown body morphing from vessel to feline. Her citation of Latin American cultural production drips with irony, nodding to the celebration of Pre-Columbian ceramics, at the same time capturing the contemporary hostility toward indigeneity. These objects are not authentic in any sense; they are Pre-Columbian “twins,” in which Velarde’s facial expressions animate what one might otherwise consider lifeless. Looking around the room, it’s as if these ceramics have been jostled out of their original contexts, victims of archeology and the white cube. In a word, they are plundered. The references are thus broad. But they always seem to come back to the artist’s own desire to parse identity—personal and collective. She also displays a sense of vulnerability as a woman confronting her own mixed-raced Peruvian body through the lens of European conventions of beauty.

Plunder Me Baby introduces Santa Fe, a place dealing with its own history of colonialism and race-mixing, to these significant bodies of work. In Velarde’s tongue-in-cheek ceramics and paintings, there is a lesson for those interested in similar questions. For me, her work and words linger on the periphery of all my recent thoughts; I can’t help but think to myself how she so deftly captures a shared existence and a shared sense of denial. Her creativity is powerful. More poignantly, it all comes from experience. “I never thought I had a feminist stance… I have been myself in my work. Everything I have is a position I take in life.”