June 22 – October 7, 2017

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

Artist Jimmie Durham is not Cherokee, and that’s a fact. Indigenous tribes in the United States act as sovereign nations that determine their own citizenship, and Durham’s name is missing from the rolls of all three Cherokee Nations. Things get a bit murkier after this, but hold that truth in your mind as a bold bottom line.

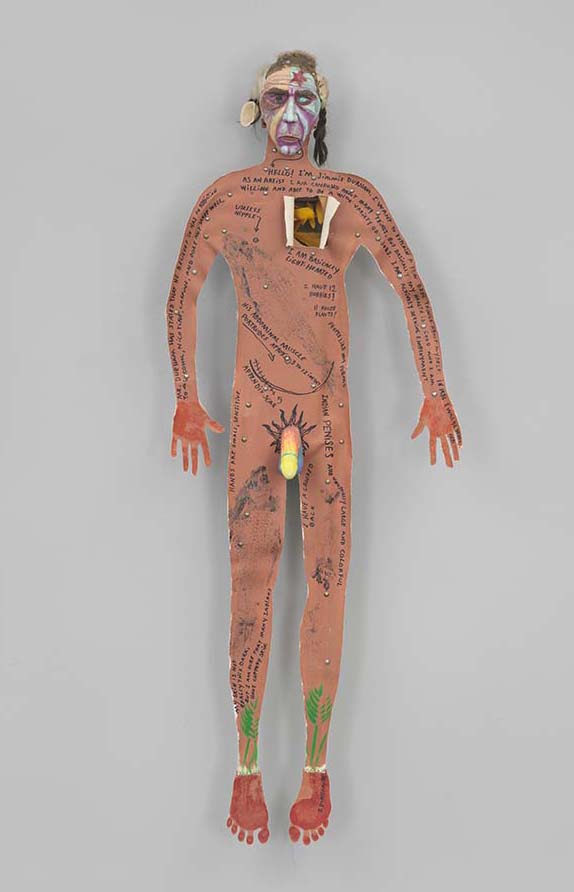

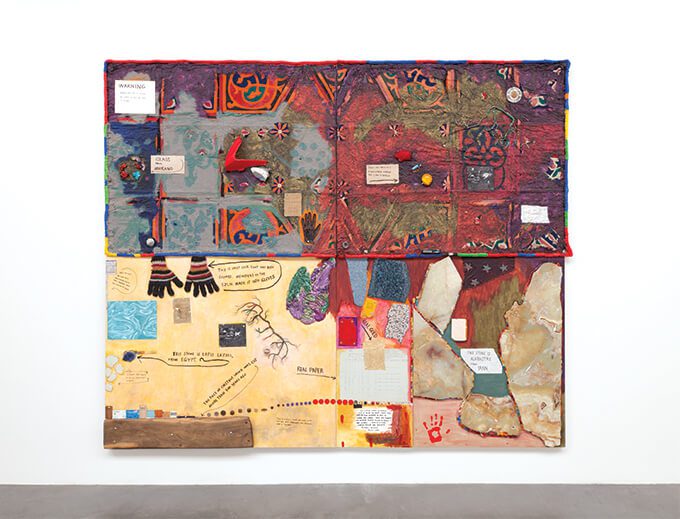

Questions of Durham’s identity have arisen due to an enormous traveling retrospective for the artist that was curated by the Hammer Museum and opened at the Walker Art Center in June. Featuring over 150 of Durham’s artworks, the show highlights his brilliance and versatility as a postmodern sculptor—but also underscores a persistent problem with the presentation of his work. The Hammer originally identified Durham as “a Native American of Cherokee descent” on its website, and the exhibition’s wall text and 300-page catalog make reference to his Native identity.

This posturing sparked a letter of protest signed by ten Cherokee artists and scholars. “Durham simply has no record of Cherokee ancestry and no ties to any Cherokee community,” they write. “To paraphrase the Cherokee author and lawyer Steve Russell, it is not who you claim, it is who claims you.”

If you’re feeling some déjà vu, it’s because the same questions came up in the 1990s. Durham (born in 1940) was a leader of the American Indian Movement that began in the late 1960s and referenced his Cherokee ancestry in artworks throughout his early career. In interviews, he told stories of speaking the Cherokee language and cooking traditional dishes in his childhood home. The passage of the Indian Arts and Crafts Act in 1990, which bans artists who falsely claim Native identity from selling their work, complicated matters for Durham.

“I am not Cherokee. I am not an American Indian,” Durham wrote in a letter to Art in America in 1993, in response to an essay about his work by Lucy Lippard titled “Postmodernist ‘Savage.’” Since then, numerous scholars have sleuthed their way through Durham’s family tree, turning up legitimate questions about his true birthplace and ancestry.

The artist moved to Mexico in the late 1980s and has lived in Europe since 1994, skirting these legal and cultural quagmires by scrubbing his work of Native American subject matter and selling internationally. However, the new retrospective’s timeline starts in 1970, and its presentation offers a rare glimpse at Durham’s enduring beliefs about his identity.

In response to the re-ignited controversy, the Walker met with Native artists and curators and crafted disclaimers for the show’s wall text and gift shop. It’s a small step in the right direction, but the institutions that house this show (it continues on to the Whitney Museum of American Art this November) are missing an opportunity for a more profound course correction.

Durham’s notions about his heritage are his own business, and no one has proposed that these museums pin him down and swab his cheeks for a DNA test. However, selecting Durham for a grandiose solo exhibition and again tying him to Native and Cherokee identities add up to gross negligence and a crime of omission.

Imagine if the Hammer and Walker had acknowledged Durham’s problematic legacy and took the opportunity to engage a constructive dialogue around its implications. There’s a way for institutions to avoid controversies like this altogether. It involves thinking carefully about where they shine their spotlights—and then taking action.