Jill O’Bryan spends her winters in New York and her summers perched high in the desert on a remote mesa outside of Las Vegas, New Mexico. She has been trekking back and forth, from coastal city grid to off-grid entirely, for twenty years, and for twenty years has sought a personal, physical relationship with the desert, its big skies and elusive waters.

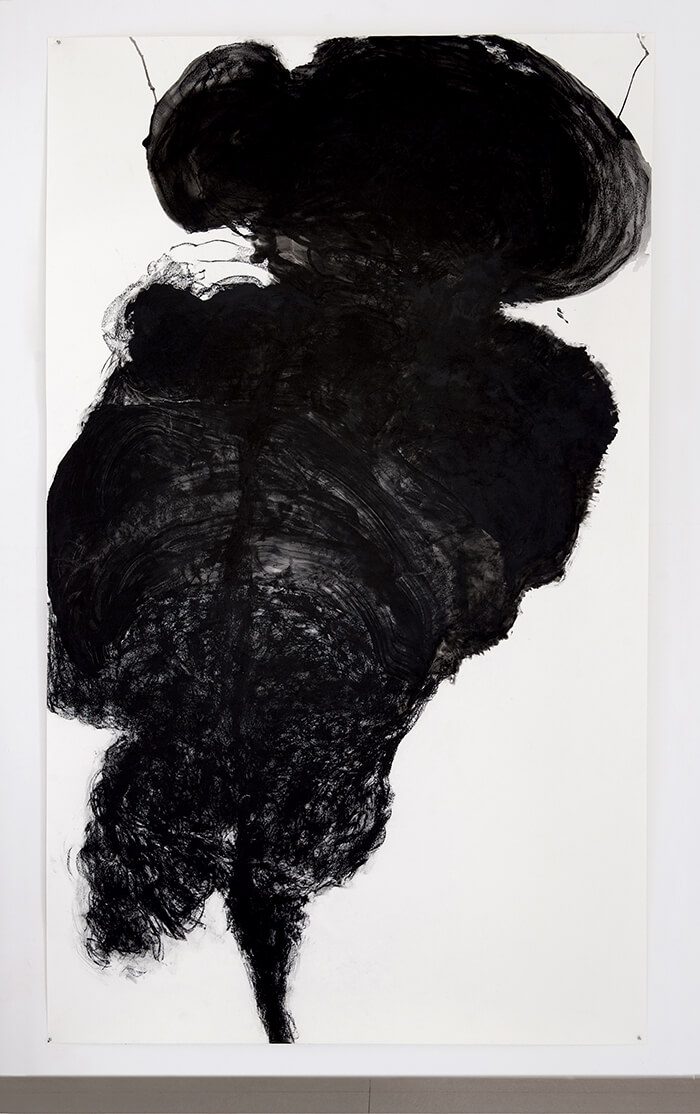

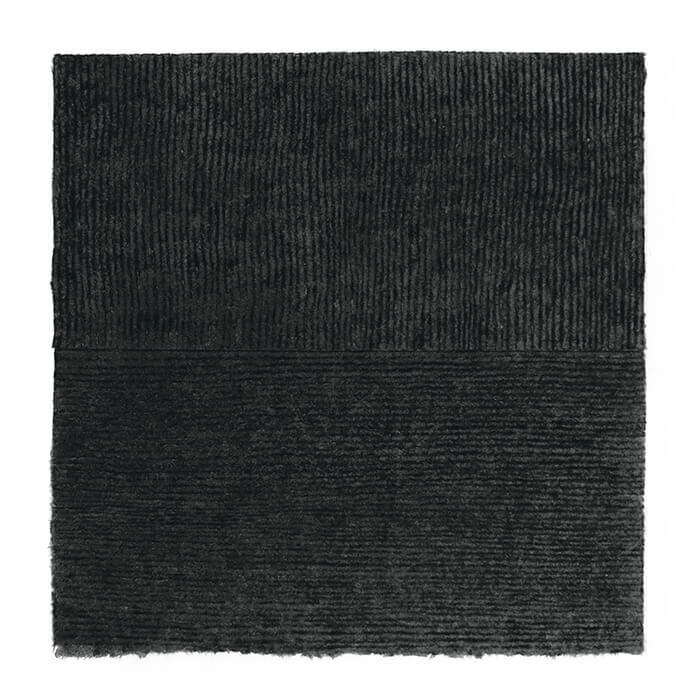

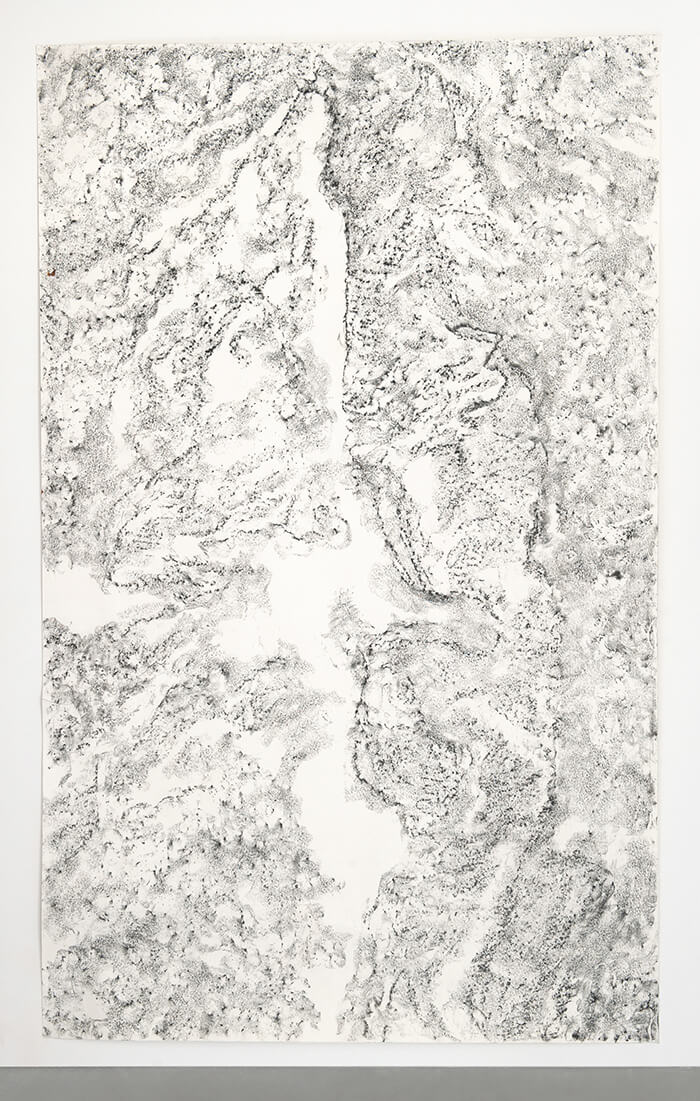

Her artistic career has tracked from beginnings in more traditional landscape painting, to abstracted, internalized landscapes, to conceptual doctoral work in academia, and now, back down to earth and body, to mark making that embeds the landscape into paper rather than describes it. Her work converses in material residues: of breath, body, sky, water, stone, paper. The series of works we discussed during our recent studio visit includes large-scale ink-on-paper drawings made by pooling ink on paper that is cupped by the rock, or by frottage, rubbings made on the earth. We also discussed her small scale “breath drawings,” in which O’Bryan makes a single stroke for everybreath she takes, saturating the paper with graphite to the point of textured fraying.

Her drawing processes embody—in the most bodily sense of the word—the experiential, meditative moments in which sky touches earth, stone touches body, breath touches paper. That embodiment bleeds into her paper: a trace of the rock, of breath—but also a trace of time, the artist’s endurance. She speaks of the rocks as delineating, shaping the sky, and it is that negotiation of space, between form and formlessness, the invisible interconnectivity between elements, that is captured in her work.

O’Bryan has an upcoming exhibition at Margarete Roeder Gallery in New York, February 27-March 24, 2018, and an exhibition at Texas State Galleries in fall of 2018. A catalogue accompanying her exhibition Mapping Resonance at the Center for Contemporary Arts Santa Fe (January 13-March 12, 2017) will be available at CCA later this month.

Lauren Tresp: How long have you been coming up here?

Jill O’Bryan: Twenty years.

LT: What was it like, from the beginning?

JO’B: When I first came up here, I was overwhelmed by the desert. I had always lived on the coast. I grew up on the water. When I came here, I didn’t quite know what to do and I needed to find a way to connect with the land.

Eventually, these frottage drawings came, but I wasn’t really intending to make big drawings when I started them. I just went out, and I thought, “Okay, I’ve got to find a way to connect with this land. I’ll just go out and lie down on it.” So I brought some big pieces of paper out, I put them on the ground, and I was just lying down on them, and I started making these drawings. So it was a real attempt to connect. Now I love the desert.

LT: How long did it take to love it?

JO’B:I was out here for a couple of years, feeling pretty uncomfortable. Not quite knowing how to deal with not having water. But now I see it, you know? Now I see the water. I see the sky; the water is there. When I first had the idea to go out and lie down on the land, I had been reading [Leonardo] da Vinci’s notebooks, and there was this section in one of the notebooks where he alludes to the shape of the air, that the sky is revealed to us by the motion of water. So I was thinking about how the sky comes all the way down to the ground, how the air just above the water is also sky. How those two forces are so dynamic when they meet up against one another.

What if I think of the sky as coming all the way down to the ground and trying to somehow be in that place where those two forces meet? What’s that like?

That’s what brought me up to lie down on the ground. I thought, “What if I think of the sky as coming all the way down to the ground and trying to somehow be in that place where those two forces meet? What’s that like? Is there something there?” I made the paper conform to the shape of the rocks and began to draw on the paper to reveal the interaction. The frottages are really incisions between the rocks and my body, or ultimately between the rocks and the sky. For me they take the place of water.

Clayton Porter: So that was twenty years ago?

JO’B: No, when I first started coming out here, I was finishing up a doctoral program at NYU, so I spent the first two summers here finishing my dissertation. I started the frottages about ten years ago—the first ones are from 2006. I did them for a couple years, then I stopped doing them. When I started again, in addition to the graphite frottages, I began an ink series called “on, and just above the ground.” These ink drawings are about being out on the rocks, but they’re not recordings of them. They’re more intuitive renderings of what’s out there.

The more I look at them, I start to think of them as animus, because they’ve really become figures that I glean from being out [on the rocks]. From doing the frottages, I started looking at a lot of petroglyphs and rock drawings—you know, things that were created on rock—and doing a lot of reading about them. There is some very poetic writing about the primal nature of that work—petroglyphs and cave paintings. They’re not really about the surface of the rock or the painting itself. They’re about images gleaned from inside the rock and inside the head, you know, a kind of merging of those two—which I love. I love that idea. I’ve gotten to the point where I go out and I look at the rocks, my relationship to them, and try to figure out where I’m going to place the paper, where I’m going to draw next. To me, it’s almost like standing in front of petroglyphs: the drawings don’t have to be there. It just feels primal. I try to cultivate that relationship I have with the rocks, with the land, as much as I can. I think that’s when it becomes interesting for me.

LT: What was your graduate work dealing with?

JO’B: My path to art making has been a bit jagged, but in hindsight I see a clear progression from looking outside to looking inside. I made landscapes and portraits when I was an undergrad. I spent a year at the Marchutz School of Painting in southern France. There I learned to see; I learned about color and line. I learned to draw. And it is there also that I learned that looking “at” something to paint meant seeing it from the inside. Landscapes are not just about landscape, they are about seeing light and getting it down in a kind of perfect, prickly, magical way… very difficult to do. Getting my MFA, I wanted to focus and paint internally, and to “push paint,” and really learn about making paintings. For the most part, these were very organic abstract paintings in blacks and earth tones that referred to internal, cave-like spaces.

When I decided to go to NYU, I was really searching for some kind of conceptual backbone for that work. I thought, “Okay, I’m going to go back to the beginning.” And for me, that was going back to the beginning of Western philosophy—to try to learn how to think about things in a more articulate and more profound way. So I went to graduate school in critical theory. I was in the art department at NYU, and took classes in the performance studies department, the comparative literature department, the German department, the poetry department. I was really lucky. I ended up writing about feminist performance art and the relationship of the body to identity. I did a whole history of the way women’s bodies were viewed throughout Western medicine, which was kind of a shock. And then I focused on the performance artist, Orlan, who takes on—full force—the stereotypes and objectification of women’s bodies, particularly in art history.

And then I came out to New Mexico. I came into the studio, and I didn’t really know where to start. I can’t claim to have a full, profound knowledge of Western philosophy, but I did learn how to think philosophically. I learned how to write. But I came into the studio, and I didn’t really know what to do. I started making these marks, just on sheets of paper, left to right, top to bottom. I realized that each mark I was making correlated to a breath, and that’s how the breath drawings started. Those were the first things that came out of that work.

LT: So that came organically, because it seems like it must be so disciplined. But it doesn’t sound that way.

JO’B: It actually came organically, yes. And I was so pleased: it was a huge breakthrough for me, because at the time I got out of grad school, I was thinking, “My God, I spent all these years of my life doing this, and the whole point was to, somehow, in some weird, skewed way, give a conceptual nature to my work. And I didn’t. I haven’t found one. I’m sitting in the studio again.” And ironically, it came out of the body and not out of the mind, which is, of course, how it always works. It doesn’t come from where you expect. Concepts imposed from the outside have never worked for me. It took five years to make the first breath drawing and they have changed significantly over the years—and are still changing.

it came out of the body and not out of the mind, which is, of course, how it always works. It doesn’t come from where you expect.

LT: Maybe it’s a New Mexico sensibility, because people tend to live more in their bodies here—as opposed to living in a city full time. Here, I think there are different considerations.

JO’B: That’s a great observation. It’s true. Compatible with being out here and feeling the land is a more acute awareness of being in the body, for sure. I feel like I have this really intense awareness of having a body, as bizarre as thatsounds, more so out here than I do in New York, where you’re distracted by a lot of things. These breath drawings have also become the backbone of my studio practice. I always have one going so that I can walk into my studio and begin working at any point in time. It’s very important to me. They keep me focused.

CP: It’s intriguing that the body work came from that sense of tension that was happening. Do you find that working in the studio throughout your career, there has been that struggle? It sounds like these bodies of work came from that birthplace.

JO’B: It happens throughout—well, I’m going through one of those times right now. I feel like I’m in a transition. It’s kind of a cliché when artists say that, but I’m trying to push what I’m doing a little further. I’ve kind of become known for these two series of work, and it’s what people expect to see. I feel that, coming into my studio, and I don’t like it. My instinct is to push back. If you’re ever at a point in your studio when you feel like you’re churning out work to satisfy a demand, that’s it: it’s over. Then it becomes making decoration, or it just loses everything.

CP: So you feel like you got to that spot?

JO’B: I do, I feel that pressure. But it’s not necessarily from the outside, it’s also from the inside. It’s a feeling that it’s time to be in that really uncomfortable place again and push forward with something else. What that is, I don’t know yet.

CP: Now, you have work hanging in the studio. You make the drawings outside and bring them in. Is it for you to contemplate the trajectory?

JO’B: No, but I have to live with them, you know? And sometimes they die on the wall.

CP: Do they?

JO’B: They do. And then I burn them. This year, I’ve been having about a fifty percent success rate, which is pretty low for me. Which is how I can tell that I need to push it. So this is all new work from this summer. I just did a breath drawing in white, which I’ve never done before, and I like it. I like that it pushes the formality of the process. There’s this grinding in. There’s also an allusion to a residue that’s a different shape.

CP: Do you focus on the breath work in New York?

JO’B: I do some of it here. I can’t make the large ink drawings there. In New York, I work on the breath drawings—primarily because I have a really small studio there, and I close myself off and just meditate and do those drawings. It works pretty well for a while. And [I make] smaller drawings. I do a lot of experimentation with things there.

CP: Do you still have a sensibility to connect philosophical thought patterns with your work?

JO’B: At this point in my studio, a philosophical sensibility comes through more in the process of making the breath drawings. I would call my work performative, of the body, intuitive. For the intellectual part—this summer, I’m reading John Cage’s letters [The Selected Letters of John Cage]. He had such an amazing ability to take the intellectual, apply it, and come up with incredible work. It’s so admirable, to read his inner thinking about it and his struggles with it, and what he latches onto and what he abandons. How he marries the two, the intellectual and the creative, is incredible. I’ve always had a drive to be able to do that, but my work just doesn’t come from there. I really rely on my own body’s relationship to being on the ground, surrounded by air, and my experience of this is totally enriched by research about Buddhism, eastern philosophical thought, and an amalgamation of everything else I’ve accumulated over the years. I’m old enough now that I’ve learned what my process is, I know where to go to dig.