I am the son of J.E.T., or Jetson, Chip Thomas said, referring to his own initials and those of his father. Thomas’s full name is Dr. James Edward Thomas, Jr., and his father, James Edward Thomas, Sr., was the original J.E.T. It’s how Chip Thomas came to his own moniker, Jetsonorama. To those familiar with the creator behind the billboard-sized wheat-paste murals in the Western Agency of the Navajo Nation, the name brings to mind a black family-practice doctor who is also a prolific photographer turned street artist. As a kid who grew up in the sixties, Thomas’s favorite cartoon was, in a funny foreshadowing, The Jetsons. When he added the suffix –orama, the name became an even more concerted throwback to midcentury futurism, like that buzzing and now-dated world in the skies where the Jetsons hovered about. But it’s also a throwback to an era when walking on the moon was just on the horizon and the detonation of the atomic bomb was a decade and a half in the rearview mirror. Jetsonorama: of the future, yet most certainly of the past.

Originally from North Carolina, Thomas first came to the Navajo Nation in 1987 to practice medicine. Before that he’d received a four-year scholarship from the National Health Service Corp to attend medical school (1979-1983). Owing the agency time for time, Thomas had to practice in a health shortage area. Rather than leaving when his time was up, he stayed for just over three decades, making his home in a community centered between some of the most beautiful landforms in the West—Canyon de Chelly, Monument Valley, the Grand Canyon, and Lake Powell. Over the course of maintaining a family practice there, Thomas also developed a darkroom photography practice (he built a darkroom twenty-two years ago). He took cues from such photographers as Eugene Richards, known to carry one to two camera bodies and use only ambient light. Thomas, who is a self-described documentary photographer with an especially precise way of talking about nearly everything, now uses a lightweight Leica M6 (“lighter than most rapper’s necklaces,” he said). He’s used other cameras in the past, all toward honing his photography game. Mostly he works in black and white. His subject matter has remained steady, too: the Diné (Navajo) people he lives and works among.

In 2009, Thomas took a three-month-long sabbatical in Brazil, where he was introduced to the work of JR, who’d been in Rio de Janeiro the previous year. JR’s portraits are iconic, usually tightly focused on facial expressions and scaled up onto the sides of buildings like very large proclamations of a shared humanity. When Thomas arrived back home, he started imagining what wheat paste on the Reservation might look like: “Driving to Paige, Arizona, I would look at the land, trying to figure out where JR would work.” But after his email invitation to the French street artist received no response, Thomas had his own photographs blown up and printed in large scale at Kinkos. That was the beginning, a repurposing of street art from metropolitan hubs for a mostly rural landscape. Figuring out how to wheat-paste continuous three-foot-wide tiles onto walls was all “trial and error,” he mused, “inspired by the DIY energy of punk and hip hop.” One of his first attempts at wheat-pasting publicly was a photo of Navajo Code Talkers installed on an abandoned roadside stand.

Sacred Landscapes

To the Diné, the space between the four sacred mountain ranges, Tsoodził (Mount Taylor), Sisnaajiní (Blanca Peak), Dibé Nitsaa (Hesperus Peak), and Dook’o’oosłiid (San Francisco Peaks), roughly forms a parallelogram and the broader realm of Dinetah. It is where the hero twins slew the giant monsters of the Diné cosmos, those beings who once killed without conscience or cause. Leetso, the name given to the yellow substance otherwise known as uranium, was one such monster. In Diné thought, it was to remain in the ground.

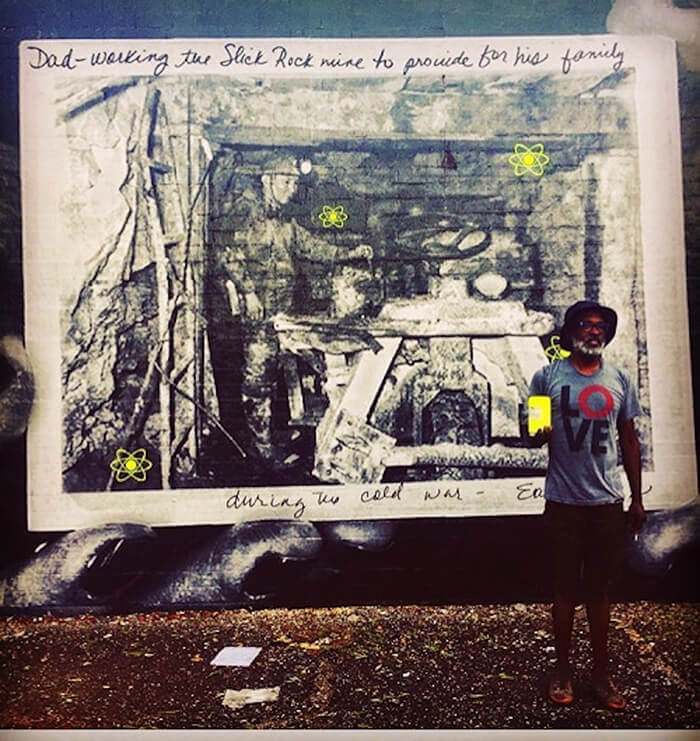

The wheat-paste murals that Thomas creates linger in the future tense of an atomic past, broaching the lasting legacy of a nuclear culture in Dinetah. In one mural installed in Phoenix, Arizona, which advertised the exhibition Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land, two hands hold a photograph of the interior of a uranium mine. In cursive, the words “Dad—working the Slick Rock Mine to provide for his family during the cold war” are scrawled as the caption. Over the course of the Cold War and until the 1980s, the federal government purchased uranium ore mined by the Diné to make atomic weapons. While the Public Health Service knew of the impacts of radiation on miners, they did not mandate that corporations provide the necessary protections, such as respirators or showers at the end of a day’s work to the miners. Thomas’s co-worker, whose mother and father both died of uranium-related cancer, showed him the memorabilia of her family, including the photograph of the mine that eventually became the subject of his mural.

Amongst the sacred, extractive, or even touristic sites, Thomas’s wheat-paste murals forge other coordinates of resilience and visibility in the landscape.

Thomas spoke at great length about the other toxic industries that have long extracted resources from the Colorado Plateau. He even asked me if I knew the five resources that have been siphoned from the depths of the Navajo Nation. I could easily name four: coal, oil, natural gas, and, of course, the uranium. The fifth resource was to me a mystery, but it was simple enough: water. The Navajo Nation, Thomas pointed out, is rich in aquifers and energy, yet “twenty percent of my patients don’t have running water or electricity. With those resources,” he continued, “the Navajos should be the Saudis, but because of the way the contracts were written to benefit multinational corporations, they’re some of the poorest people in the nation.”

As a doctor, Thomas has seen the collateral damage of this imbalanced system. High rates of lung ailments and various cancers are consequences of uranium mining and a mine-tailing spill in 1979—the Church Rock Disaster—which rivaled Chernobyl and Three Mile Island. With the end of the Cold War, more than five hundred superfund sites were left behind with little to no cleanup. Homes built from the irradiated rock blasted from the sides of Mount Taylor also remain. Alcoholism, diabetes, and suicide are prevalent, too, the traumas of a colonialism that never ended.

Amongst the sacred, extractive, or even touristic sites, Thomas’s wheat-paste murals forge other coordinates of resilience and visibility in the landscape. Many are scaled-up portraits whose Diné subjects are caught in an array of facial expressions—joy, wonder, and pensiveness—all perched along the sides of highly trafficked roads on silos, water tanks, the sides of buildings, concrete pilings, or even billboards. There was once even a Google map showing all of their locations within the 120-mile radius where he pastes, a relatively small corner of a reservation that totals about 27,500 square miles. The majority can be found between Gray Mountain and Bitter Springs on Highway 89. Others are located between Red Lake and Kayenta on Highway 160. The major thoroughfares that take tourists to iconic landforms are the same that the Diné use. Both are his audiences, but he is in primary dialogue with the Diné: “In my family practice, I’m trying to create an environment of wellness. And in my art practice, I am reflecting the beauty of the community back to itself.”

His portraits feature people from every age group, including toddlers, children, adults, and elders. In the latter, his particular way of emphasizing contrast plays up the textures of elders’ faces, their wrinkles happily carved over years of expressiveness. He crops liberally for a tight focus on one aspect of the body. In one mural pasted onto an empty roadside billboard, for instance, there is simply an outstretched arm emblazoned with the words “Native pride.” Thomas recalled that he pasted this particular mural at night, in true guerrilla-art fashion, “scampering up and down the ladder” every time a car’s headlights came into view. It took about four hours to complete.

Other murals are non-human-centered. In several wheat-paste murals, for example, he has pictured Lola, a legendary, but irradiated, dog renowned for her shepherding capabilities. She is the atomic super dog who, in Thomas’s visions, is always hot pink. In one particular installation, she can be seen on one wall and her sheep wheat-pasted onto another, just behind her. Another mural located here in Santa Fe features only corn in all of its multicolored glory. I can recall driving down Agua Fria and watching Thomas paste it on the front of Biocultura. Two hands came into view, bearing forth the beautiful gift of several cobs from the front of the building. The rest of the mural wraps around the building and ends with a gardener. Another triptych features hands making fry bread with the words “How to Make Fry Bread.” More recently, a Los Angeles–based social impact agency, MAL\ FOR GOOD reproduced Thomas’s portraits in an ad campaign for NPR’s Morning Edition.

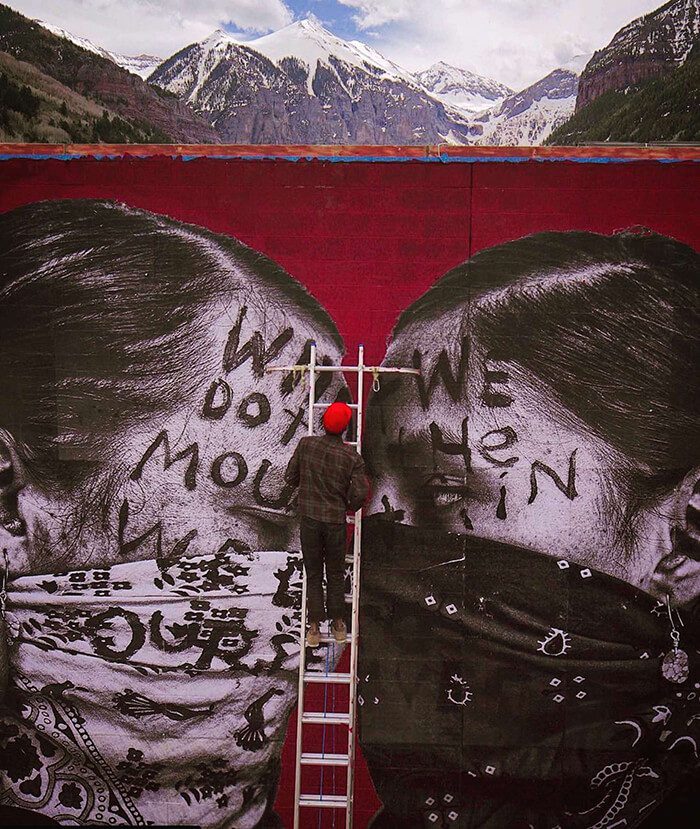

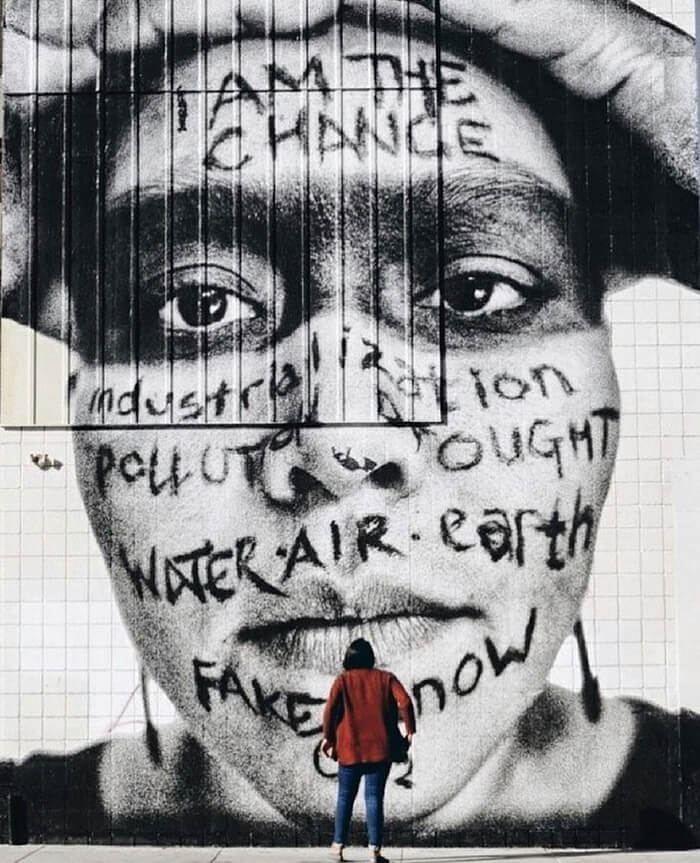

And while these examples aren’t outwardly activist, others certainly are. In one mural, commissioned by 350.org, a baby looks slightly upward towards a dark cloud hanging overhead. “It’s an actual piece of coal,” the artist pointed out, a lump with an especially dark and craggy underside and a metaphorical dark cloud that hangs over future generations. Coal is a source of energy for much of the Southwest, and, in the Navajo Nation, its mining offers a form of income. Yet the relationships between corporate mines (like the now-closed Black Mesa coal mine and the still-operational Kayenta mine, run by Peabody Energy) and the Diné have been historically exploitative. In 2011, moreover, Thomas produced a set of wheat pastes that centered on friends’ opinions of the Forest Service’s decision to allow artificial snowmaking from wastewater on San Francisco Peaks, one of the four sacred mountains. Thomas photographed his friends whose words were written across their own faces, wheat-pasting the images in various locations. Klee Benally, an activist and musician, was pictured with his wife with the words “What we do to the mountain, we do to ourselves” scrawled across his face. Stephanie Jackson, then a graduate student at Northern Arizona University said, “I am the change,” also written in capital letters across her forehead.

Full Disclosure

Thomas encouraged me to look up the history of wheat paste, an adhesive used as far back as antiquity. Its main gluing property can be found in wheat (or other vegetable) starch as it boils with equal parts water. Circus posters, commercial bill posters, labor posters, and even the work of Toulouse-Lautrec all adhered to walls with wheat paste of some form, also dubbed Marxist glue. Swoon, Shepard Fairey, JR, and Jetsonorama have all come into their own as inheritors of this particularly rich and counter-cultural way of making messages public.

“Full disclosure: I don’t actually use wheat paste anymore,” Thomas revealed. I couldn’t help but chuckle in surprise as I thought about the irony of an artform long defined by a medium that is more symbolic than actual. For Thomas, though, even if he doesn’t mix up batches like he used to (from Cortez Bluebird Flour, no less), the medium’s implications recall both hope and criticism. And on a logistical level, the thick paste tends to leave a milky surface that obscures the deep contrast in grays that makes his photographs so eye-catching from great distances. Acrylic gel medium has taken its place, holding up better to the elements, as well as helping to maintain the properties that are inherent to black-and-white photography.

Thomas has very decidedly centered his work on the Navajo Nation, his murals forging a cumulative portrait of people and place that can only come with time and dedication.

At some point in our conversation, Thomas asked me what I thought was the difference between his work and that of JR. He didn’t want the two to be confused. After thinking a bit more, I can now fully articulate the answer: while JR has been a global nomad, Thomas has very decidedly centered his work on the Navajo Nation, his murals forging a cumulative portrait of people and place that can only come with time and dedication. In that way, his perspective differs from JR by virtue of his regional base and the attention he pays to light and darkness: the clouds, bleaching sun, and hard shadows are the Western skies’ signature—and his own. The faces and stories are all wrapped up in the images as well, making for a very public personal dialogue that achieves a sense of intimacy even in large scale.

“As a person of color from the South,” he summarized, “it’s very easy for me to identify with historically oppressed groups, and the skill of photography lends itself to amplifying and advocating those voices. Even when I was doing straight photography, my goal was always to challenge the dominant narrative.” Indeed, his works are both a challenge and an invitation, messages rendered for viewers always on the horizon