In bold pop culture style, Santa Clara Pueblo artist Jason Garcia envisions Native futures by challenging narratives that have always kept us in the past.

Santa Clara Pueblo (K’haP’o Owingeh) artist Jason Garcia (Okuu Pín) waves me up the muddy driveway, a result of recent rains hitting Northern New Mexico just a few weeks shy of the summer solstice. Garcia is son to a family made up of generations of traditional Pueblo pottery makers, a legacy that marks his creative space and its surroundings. From the front windows of his multi-room studio, which once belonged to his paternal grandparents, he points out the homes of various relatives, including his parents’ house, where he does his outdoor firing.

In that same room sits a table full of plastic containers holding a variety of mineral pigments that he inherited from his godmother and aunt, the late Santa Clara potter Minnie Vigil. From her, he also received clay, temper, and polishing stones. Hand gathering and processing traditional materials like these is time-consuming and labor-intensive; these gifts will spare Garcia hours of digging, hauling, pulverizing, grinding, and sifting. He uses the term “cultural patrimony” when describing these polishing stones, which are used to add sheen to the blackware and redware for which Santa Clara is renowned: “Those aren’t sold, those are given.” His mother, potter Gloria Garcia (Goldenrod) has some from her mother, her paternal grandmother, and generations before them.

On a shelf in the adjoining room lay several hand-flattened clay tiles waiting to be painted with mineral pigments and fired in preparation for the upcoming Santa Fe Indian Market, which Garcia’s been consistently attending as a family member or as an artist since he was three weeks old. Back then, he slept under his paternal grandmother’s table of pottery. He started showing his own work there when he was around four or five years old.

I discovered that Garcia and I had a similar upbringing: Gen Xers raised with our Pueblo traditions but fed a steady diet of pop culture. We laughed about a shared appreciation for the ’70s sitcom, What’s Happening!! (in particular, the episode guest-starring the Doobie Brothers), and talked about misconceptions from outsiders that we led an isolated existence growing up in our rural villages (I’m from Cochiti Pueblo), despite the semi-regular trips we made with our families to urban areas, and the movies, music, books, and comic books that we consumed—all offering us a window to the outside world. Pop culture references throughout his work detail specific influences: Star Wars, Back to the Future, Conan the Barbarian, and the list goes on.

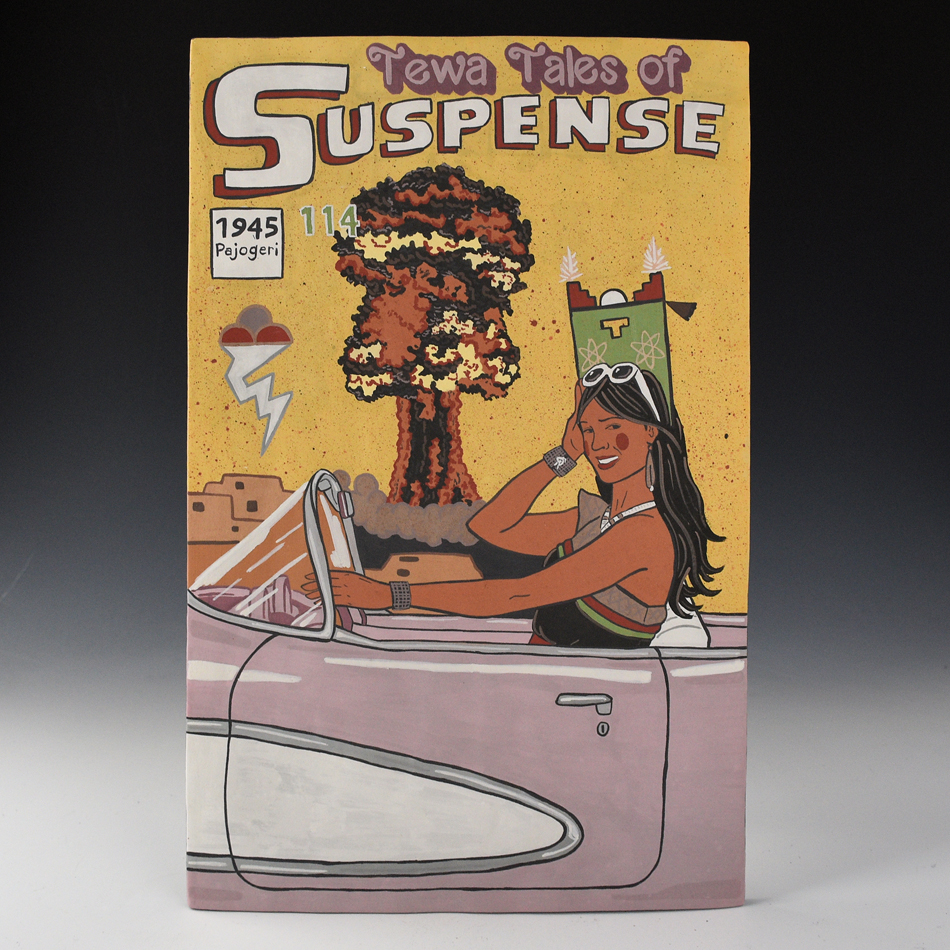

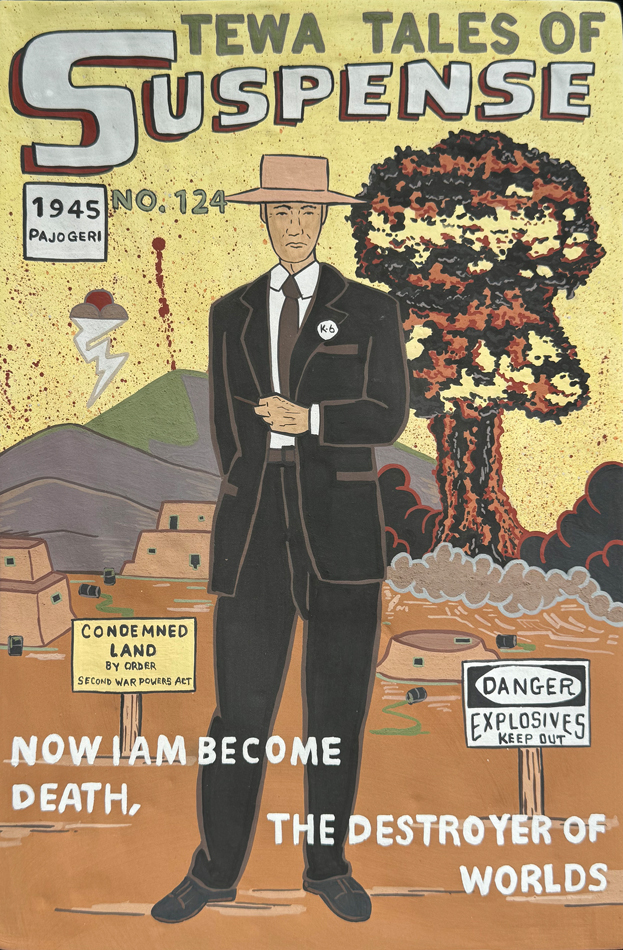

Garcia and I worked together briefly when I was a community curator on the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture’s permanent exhibition, which includes several 1680 Pueblo Revolt serigraphs from his TEWA TALES OF SUSPENSE! series. He made them while working on his MFA in printmaking at the University of Wisconsin. He continues to make serigraphs in his studio on a machine that he hopes to someday share with other Native artists by offering a residency.

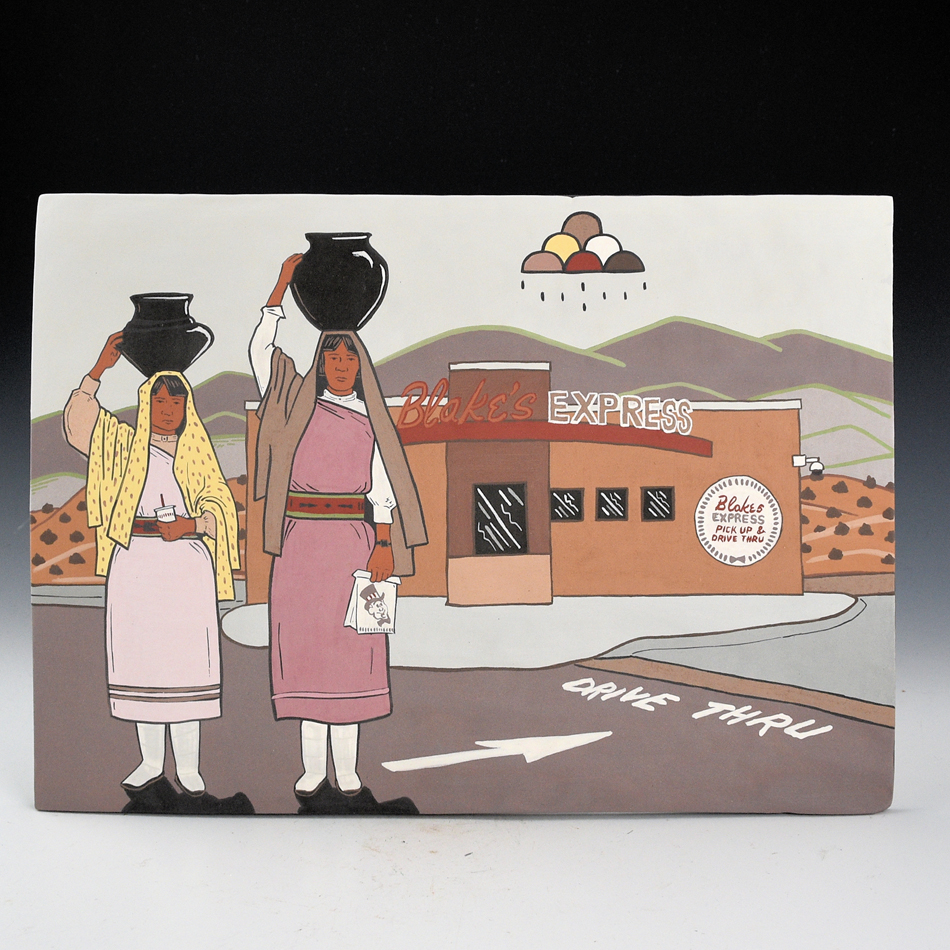

TEWA TALES OF SUSPENSE! has become Garcia’s vehicle for exploring Pueblo creation and migration stories, tales, and historic events using comic book-style illustration, in ways that illuminate Indigenous survivance. The result is a body of work that counters narratives that falsely portray Native people as belonging to the past. For Garcia, this cultural continuity is evidenced by “the fact that we [Santa Clara people] are still here, still in K’haP’o Owingeh. The fact, that I know that K’haP’o Owingeh is the traditional [Tewa] name.”

A more recent addition to the series, #124 PAJOGERI 1945 ‘Project Y’, addresses Indigenous invisibility in Oppenheimer, the blockbuster movie about the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist in charge of developing the atomic bomb at Los Alamos National Laboratory, located twenty miles from Santa Clara (and ten miles from my village). Garcia explains, “This was a very significant event that happened in our own history… nuclear colonization.” He depicts Oppenheimer standing in front of a Pueblo village with a nearby exploding bomb and Oppenheimer’s utterance emblazoned below, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Garcia asks, “What kind of worlds? Destroyer of the ‘Tewa world’?”

Garcia developed TEWA TALES OF SUSPENSE! in response to the lack of Pueblo-voiced content directed at mainstream and Native audiences, detailing events in our history. However, he did draw inspiration from what little existed, including the 1980 Tricentennial commemorative run marking the 300th anniversary of the Pueblo Revolt, and Surviving Columbus (1994) and Gathering up Again: Fiesta in Santa Fe (1994) (two films exploring the impact of settler colonialism on our communities). Garcia builds on these works, ensuring that our future voices will continue to reflect this narrative change because as the Pueblo world already knows, there is no delineation between our past, present, and future.

•

At the end of our visit, Garcia handed me two prints. I responded, “I’m sorry, I can’t accept these.” I explained the publisher’s policy prohibiting writers from receiving gifts, aware of ethics regarding journalistic integrity and impartiality as defined by Western standards. But my reaction felt wrong. Pueblo interconnectedness is built on reciprocity and generosity; this is how we’ve ensured our well-being as a community. We have faced droughts, colonization, genocide, land dispossession, boarding schools, and other apocalypse-like events in our history, together.

Garcia had also given me his time, graciously welcoming me into his studio where we exchanged art, stories, and laughter. I accepted the prints from my heart, as we do in the Pueblo way. I wished I had a small token to give him, nothing major, maybe a few bundles of recently harvested Indian tea, something to uphold the spirit of interdependence with which we were both raised. Moments like these are reminders that while we live in a contemporary world that operates with different norms, we do not live in a world apart from our ancestors; we carry their values within us, and I’m optimistic that we still will, into the future.