At age eighty, James Surls, an internationally recognized artist who works out of a rural Colorado studio, continues telling stories through his sculptures, drawings, prints, and rubbings.

The discoveries we make at the edge of our clearing in the forest are given shape by the nature of our looking. —Joseph Chilton Pearce, The Crack in the Cosmic Egg: New Constructs of Mind and Reality (1971)

Colorado State Highway 82, which connects to the road that leads to James Surls’s Missouri Heights studio, is lined with flowers—Asian poppies, scarlet bugler, yellow sweet clover, purple larkspur, sunflowers. When I pull up to the studio, I’m immediately greeted by more tiny ambassadors—scarlet globemallows and pale blooming bindweed.

All this florescence is fitting because the Umlauf Sculpture Garden and Museum in Austin, Texas, will soon showcase Surls’s large-scale piece Fourteen Hanging Flowers, with an opening planned for December 7, 2023. In conversation about the upcoming event, Surls mentions a favorite Butch Hancock song “Long Sunsets,” which features the lyric, “Winter knows what spring forgets.” The song is about mortality and considers the brief blossom that is life—for flowers and for everyone.

Not to imply that Surls is at any type of end. He no longer wields his six-foot-bar chainsaw—“it’s like holding a Volkswagen”—but he works and still goes strong every day

On arrival, I was greeted by Tai Pomara, Surls’s assistant and nephew of Texas painter John Pomara. He’s working on a new Surls piece, one of his number-based flowers.

Number, a fundamental truth in our universe, comes up again and again in Surls’s work. Dot, line, and plane are just other ways of saying one, two, and three, but you’ll find Surls seeking it in the personal, too. When gallerist Max Hutchinson turned fifty-five in 1981, James and his life partner Charmaine Locke spent hours weighing black diamond watermelons from their abundant gardens, determined to find one that weighed fifty-five pounds. They succeeded, and in the subsequent celebration joyously participated in the birthday feast.

But for some small side spaces, the Missouri Heights studio is essentially three rooms—the main work area, a clean room, and a large downstairs room that houses work from six decades. To say Surls is prolific is like saying you can’t step in the same river once. Obvious, but with paradox thrown in for spice.

Looking through the closely packed third space is like looking through the East Texas thicket in the Splendora compound north of Houston, which served as their home and studios for over two decades before their 1997 move to Colorado.

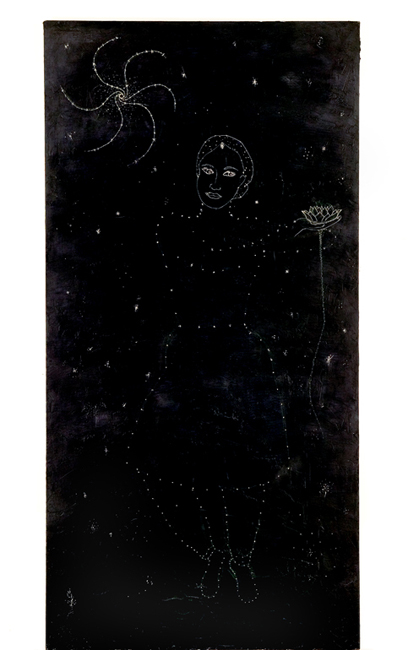

The woods were so dense back then that on walks, especially when strolling home from a neighbor’s house in the dark, James and Charmaine were forced to seek the night sky for navigation. The road was flanked by seventy-foot trees, so the road-wide band of stars was all that revealed their route toward home—almost as if the figure in Locke’s Night Wonder was herself their guide, offering the couple their own personal Milky Way to follow.

“It was so dark you couldn’t see the road. Looking up was the only way to know where we were going,” recounts Surls. “Looking up” falls neatly within the lexicon of phrases he writes on his drawings and could very well serve as the title of one of his sculptures.

Surls, now in his eighth decade of life, also continues looking forward. Since his late 2022 solo exhibition Axe and Pencil at the Bale Creek Allen Gallery in Fort Worth, his exhibition activities have included a two-person show with Locke at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art; an ongoing collaboration with the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company; and a major solo exhibition Nightshade and Red Bone at Kaneko in Omaha, Nebraska, which is on view from March 24 through August 13, 2023. This show will be accompanied by an extensive catalogue with essays by Paul Schimmel and Stephen Harrigan.

In October of this year, Surls and Locke will work in the Todi, Italy, studio of Beverly Pepper, who passed away in 2020 at ninety-seven. Pepper (2013) and Surls (2020) each received the International Sculpture Center’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

But Surls’s achievements extend beyond his prolific production. After leaving the Splendora studio for close to twenty years, except for the occasional creation of new work there, Surls and Locke felt that the time was right to transition their former studio to an exhibition space, with the public moniker Splendora Gardens. What followed were several group shows, including the annual flower-themed exhibition and a Texas Sculpture Group project. In 2023, this transitional spirit expanded with an even wider vision to include the woods, which comprise 90 percent of the Splendora property southwest of Cleveland, Texas.

On Surls’s eightieth birthday, which took place on Earth Day weekend this past April, Surls and Locke opened an exhibition at the Locke Surls Center for Art and Nature (formerly Splendora Gardens). The project A Gift from the Bower, inspired by the mating rituals of male bowerbirds, features several open spaces connected by pathways through the woods. The show includes newly commissioned works by fourteen artists and artist teams in collaboration with musicians, performers, and writers.

A Gift from the Bower will honor Houston sponsor Diverseworks with a closing reception on November 18, featuring a performance by legendary sax-expansion artist Dickie Landry, who, as the first musician to play in Surls’s Splendora studio, “blessed” the space in 1984.

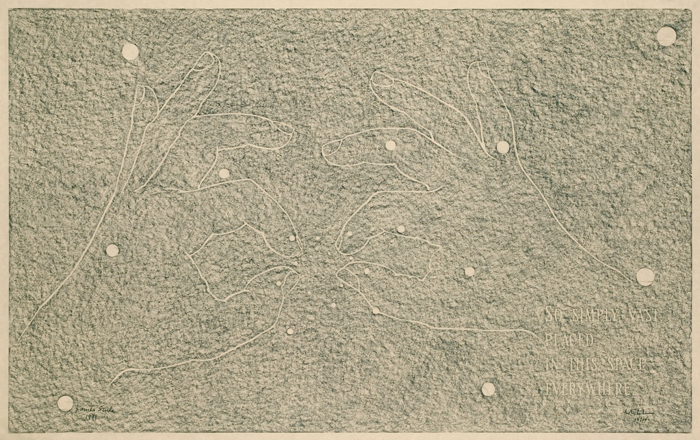

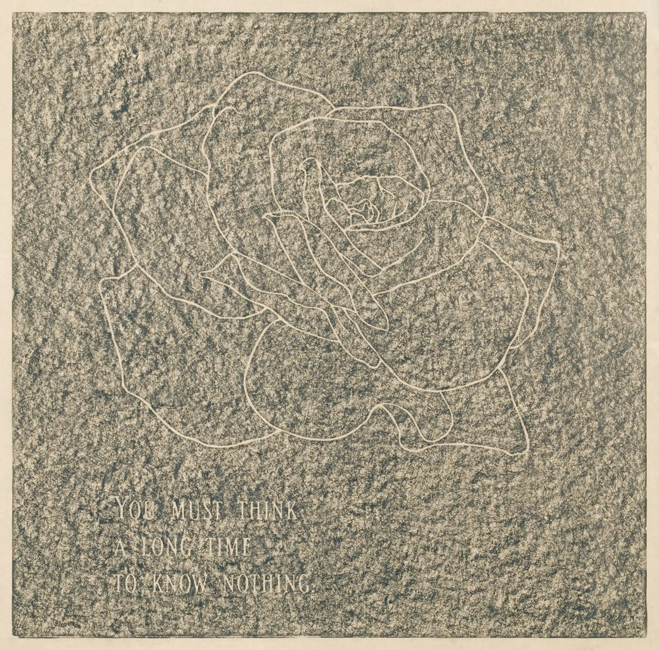

Running parallel to A Gift from the Bower, The Creeley/Surls Project offers work from Surls’s creative relationship with poet Robert Creeley in the form of seven granite stones engraved with Creeley’s poems and Surls’s images in response to Creeley’s works. Rubbings have been made from the stones and are the first exhibition in a new building dedicated to “clean work,” which was completed at the compound just in time for the Earth Day celebration.

Surls’s association with Creeley reaches back to the late ‘70s when they met at a reading that Creeley delivered at a John Chamberlain exhibition at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and to the late ‘80s when they collaborated on Poet’s Walk at Citicorp Plaza in Los Angeles. Terry Allen and Philip Levine were another artist-poet combo who were part of the project.

“I knew I was in the presence of someone who had been touched in mind and soul by a force greater than our own,” says Surls about hearing Creeley, who passed away in 2005, read at the CAMH.

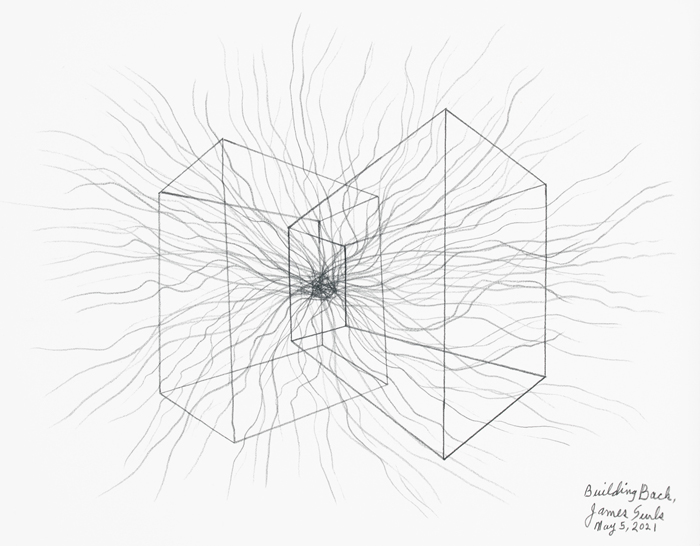

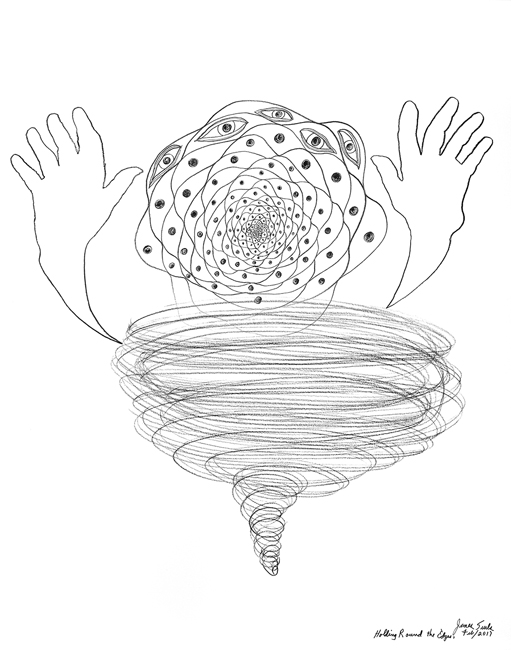

Creeley’s assertion that “form is never more than an extension of content” goes to the heart of something his poetry and Surls’s art have in common. Surls knows that if he sees a vine squeezing the circumference of a tree, the ghost of the vine is within, waiting for him to free it by making use of the twirling form he sees in his mind’s eye before even taking the tree. The coiled energy trapped in the tree reveals the strength of the vine, just as the tree’s potential for sculpture unlocks the vitality wound in his being. Surls is no barophobe. He figures if something can be done, he can do it—with assistance from the tree.

Surls is a guy true to his East Texas roots, making art that was honest to the experience available to him as the son of a carpenter, who built the house they lived in. During a 1982 panel discussion at the International Sculpture Conference in Oakland, California, an audience member asked Surls about his choice of materials. His answer revealed an egalitarian nature: “Anyone can get wood.”

It’s been said that Surls’s emergence in the ‘70s was an answer to Minimalism, and it’s true when Western art history is the frame you’re looking through. But the argument may also be made that Surls’s work is straight-up storytelling, as natural as a bird song. This view allows for accessible art—anyone can respond to a story, art historical awareness or not. Or maybe all that ‘70s and early-‘80s narrative art that came to challenge historical categories like field painting and Minimalism reveals that it’s really all storytelling. Even a subjectivity-denier like Frank Stella eventually had to face the white whale.

Another question Surls fielded at the same conference pertained to his single-decade rise to art stardom. His answer: “It’s like riding a bullet.”

The simplicity of this metaphor contains so much that has remained true of Surls. No one sets out to create a zeitgeist—it’s those keeping their head in their work that turn out to be the creators of what rises.