Its Honor Is Hereby Pledged: Gina Adams

June 6-November 2, 2019

University of Colorado Art Museum, Boulder

Gina Adams considers herself an Indigenous-hybrid artist involved in a variety of craft-based work rooted in her heritage. Yet her commitment to art-making is equally matched by the extensive research she conducts in libraries, museums, and databases. Its Honor Is Hereby Pledged: Gina Adams is the product of Adams’s deep-dive into American history. It is a stunning collection of works intent on truth-telling, making it all the more relevant and poignant. Adams’s concerns include our country’s tarnished legacy of broken treaties with Native Americans during the nineteenth century, as well as the deleterious effects of Anglo settlements on Indigenous lands during the era of Manifest Destiny. In addition, the works speak to the marginalization and appropriation of Native American culture. Adams is of Ojibwa, Lakota, and European descent, and her work pays tribute to her ancestors while assertively presenting her own point of view.

The exhibition consists of four installations, with Broken Treaty Quilts (2013-ongoing) dominating the show as viewers walk in. Adams takes the language of treaties—such as the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) and the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851)—and painstakingly reproduces the words using hand-cut calico fabric. In turn, the words are sewn onto antique quilts, all ten of which hang from the ceiling in a way that allows viewers to wander among them. If the words seem indecipherable, it’s to suggest the typical obfuscation in the language of treaties.

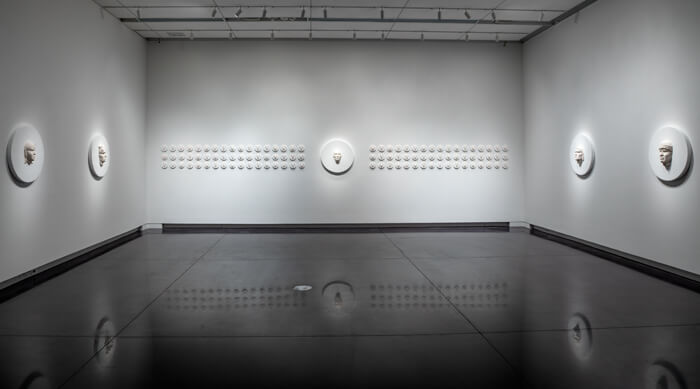

A second installation, Ancestor Medallions (2019), appropriates the idea of presidential medallions such as those given to chiefs upon signing treaties. Eschewing presidential insignia, Adams created more than one hundred medallion-like porcelain busts of Indigenous faces, a few of which depict her own ancestors as discovered through research. A third installation, American Progress (2019), focuses on Manifest Destiny and the way it swallowed up Indigenous lands. Adams depicts the tragedy straightforwardly, by juxtaposing a wall-length archival photo of a mountainous landscape with pink and red vinyl lines stretching above and below. The lines represent the Lewis and Clark expedition and the Transcontinental Railroad, both of which undulated across the West, disrupting Native settlement.

A fourth installation is tucked in a separate room and features three elements: historic photographs of Native American chiefs presented behind an encaustic layer to suggest marginalization and disappearance, an array of basketballs covered with iconography to represent various aspects of Native history and culture, and fabric banners depicting images and words redolent of Native struggles through the years.

Adams positions her art-making and research as a passage toward emotional healing and reconciliation with the past, given that her ancestry encompasses both the displacement of Indigenous peoples and westward Anglo colonization. The aesthetic appeal of her work is almost secondary to the messages, she said in a recent phone interview, adding, “You have to delve into the past in order to understand and make change in the present.”