Indelible Ink: Native Women, Printmaking, Collaboration

February 7–May 9, 2020

University of New Mexico Art Museum, Albuquerque

An online exhibition catalog is available here.

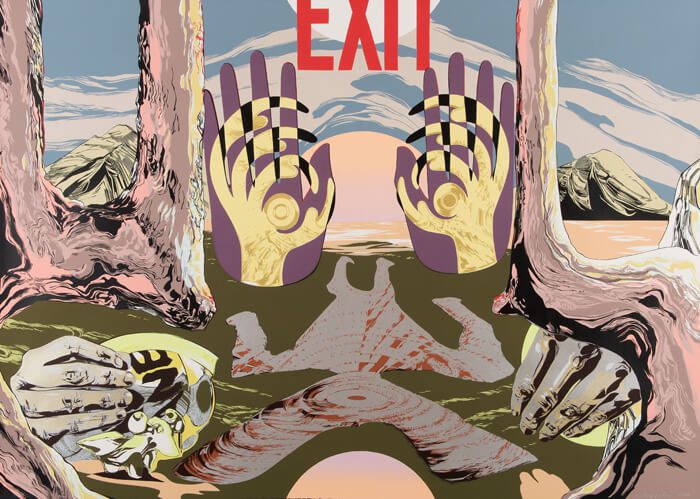

The beauty sometimes masks the pain in Indelible Ink. The exhibition, one of two new spring shows at the University of New Mexico Art Museum in Albuquerque, displays pieces by nine multigenerational Native American printmaking women whose artwork stuns with originality, beauty, and color. But the lithographs, screenprints, monoprints, and letterpresses—which were created in concert with five nationwide print studios—including Albuquerque’s Tamarind Institute and Santa Fe’s Fourth Dimension Studio—also illustrate the historical trauma that impacts Native people today.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Salish and Kootenai), likely the most recognized name in the show, displays six works that touch upon themes such as settler colonialism and the loss of Native food sovereignty. Her five-color lithograph, Indian Heart, with its soft pink background and faint ink drawings, reveals dark-hued commentaries on environmental injustice via the destruction of the buffalo, decimation of food supplies for fish populations, militarism in the United States, and Indian stereotypes that are used to sell commercial goods.

Other works, such as the four-color lithograph Trust and Loss by Dyani White Hawk (Sicángu Lakota), show the results of the federal government’s devastating policies. White Hawk recreated a newspaper page from December 5, 1929, that shows plots of purchasable lands on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Porcupine quillwork patterns overlay the sale listings, which, White Hawk writes, were a tangible result of the Dawes Act of 1887, where Native lands were subdivided into plots for commercial use, often by white settlers.

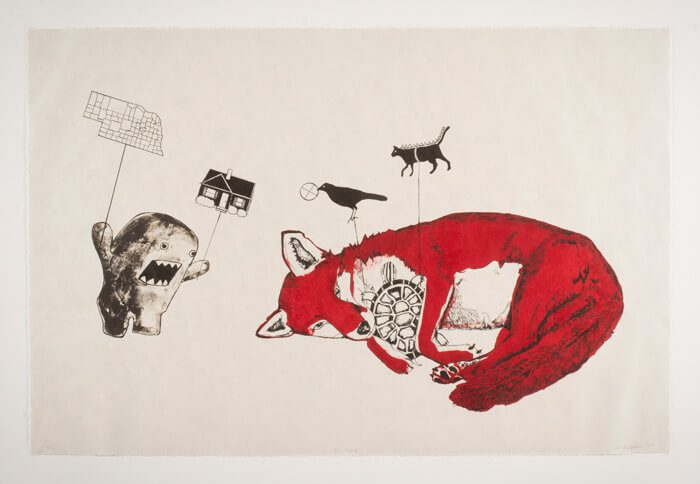

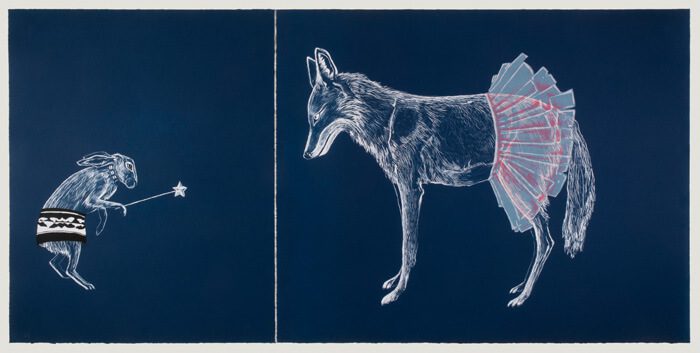

Some works, such as Trickster Showdown, are blackly comic interpretations of Native culture and self-identity. Julie Buffalohead (Ponca) depicts a star wand–wielding rabbit and tutu-wearing coyote, in mystique-stripped positions, against a bare background that’s a deep shade of cyanotype cerulean blue. The work doubles as an illumination of Buffalohead’s multiplexed experiences as a biracial woman. Then there are pieces that are next-level gorgeous: Raven 2 and Raven 3 are magnificent expressions of contemporary printmaking, via a deconstructed technique employed by Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi).

The Mary Statzer–curated exhibition, which showcases works from 1993 to 2019 that are either on loan or part of UNMAM’s permanent collection, also features excerpts of new interviews with the artists that explain their inspiration or workflows. These tidbits enhance a show that’s already resilient and self-determined to the core.