Ralph T. Coe Center and various locations, Santa Fe

August 14, 2018 – March 2019

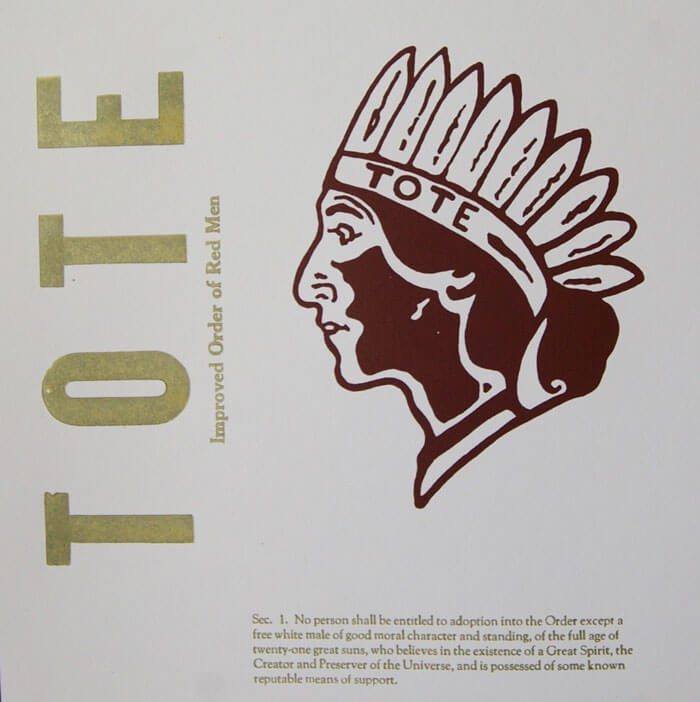

On the streets of Santa Fe this fall, you might stumble upon a newspaper box you’ve never seen before. For three dollars in quarters, you can retrieve a printed sheet of paper, itself a kind of news. Jacob Meders’s series of prints, TOTE, re-appropriates the appropriated imagery of the Improved Order of Red Men, one of the United States’ oldest fraternal orders. Text from one of the prints encapsulates part of the Order’s mission: “Keeping alive the customs and legends of a once-vanishing race.” The Improved Order of Red Men took it upon themselves to “save” Native culture by appropriating it, often perpetuating stereotypes that had nothing to do with truthful representation. Meders, by reclaiming the Order’s imagery, calls out its history of hypocrisy. Prints carry with them politics, often in their content but also with their technique. They’re outside the discourse that presupposes that preciousness is a necessary aspect of quality.

Meders’s newspaper box is one of two that will appear in various locations through next March during IMPRINT, a series of exhibitions and events organized by the Ralph T. Coe Center for the Arts. Curators Bess Murphy and Nina Sanders (Apsáalooke), along with the six artists in the show—Jamison Chas Banks (Seneca-Cayuga, Cherokee), Jason Garcia (Santa Clara Pueblo Tewa), Terran Last Gun (Piikani), Dakota Mace (Diné [Navajo]), Jacob Meders (Mechoopda/Maidu), and Eliza Naranjo Morse (Santa Clara)—conceived of IMPRINT as a means to make their work and its themes accessible to a wide audience and to disrupt ideas of how art can function in public spaces. In addition to the newspaper boxes, in which works by all six artists will be on offer, large-scale wheat-pasted images will be installed throughout Santa Fe (all locations will be announced on social media). The effect of such wide circulation is not only increased access to artworks but a democratization of access; often works will be free or priced so that nearly anyone can own the work. To kick off IMPRINT, three issues of the Santa Fe Reporter featured collaborations by its artists on its covers (don’t miss The Magazine contributor Alicia Inez Guzmán’s accompanying article). Likewise, for the month of August, Axle Contemporary, itself a roving venue that brings art to its audience instead of the other way around, featured prints by all six artists, as well as a free letterpress workshop by Meders.

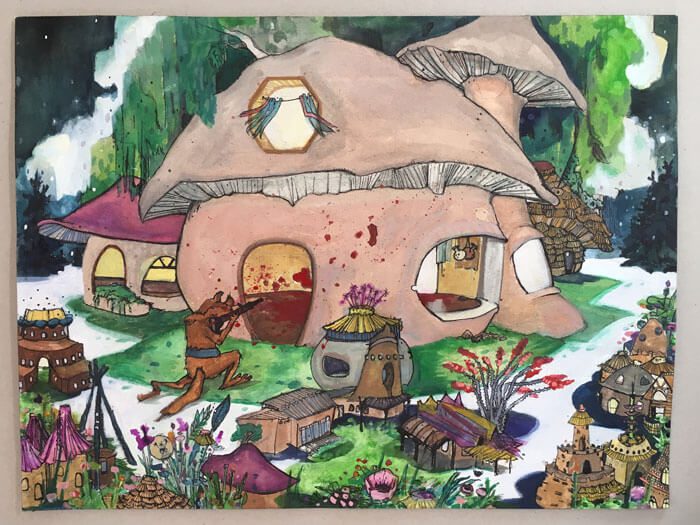

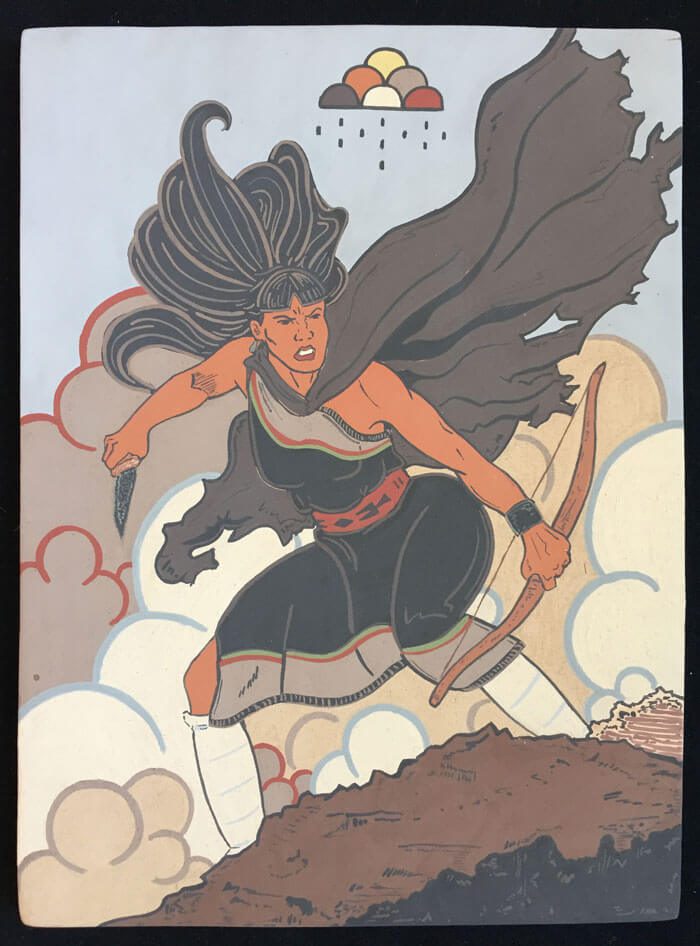

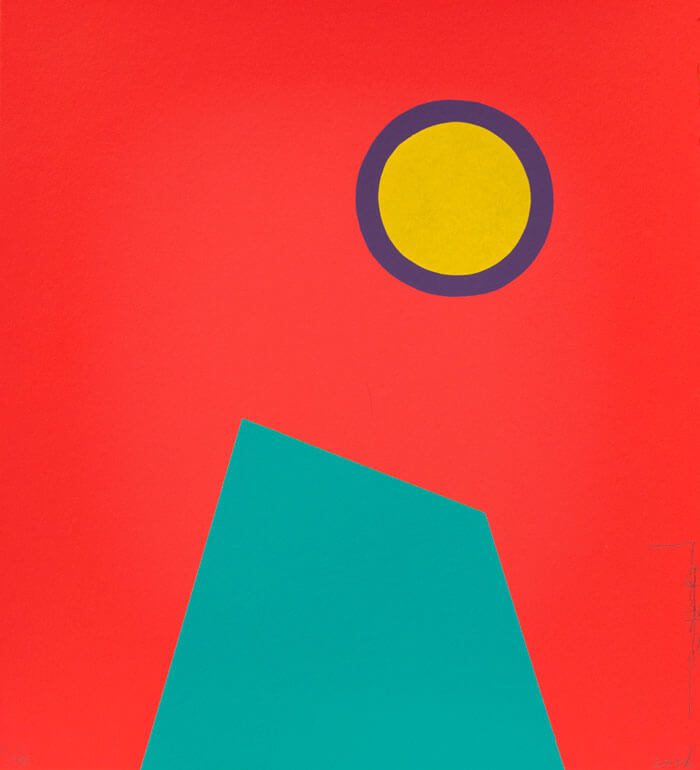

Although the artists participating in IMPRINT have embraced the ephemerality of printmaking, the themes and ideas they grapple with are anything but fleeting. Banks’s images of the Thick-Billed Parrot, an endangered species that may once have proliferated in northern New Mexico, hearken back to aviary images on Pueblo pottery—an example of which is on display near Banks’s parrot-printed kites that hang from the Coe ceiling. Garcia’s works effortlessly blend images of Pueblo women in Indigenous dress with technological apparatuses—antennae, cell phones. His print series Tewa Tales of Suspense adopts the style of comic books to portray vibrant, heroic women in mid-action. Last Gun’s silkscreens, inspired by the landscape of his Montana homeland as well as New Mexico, similarly adopt a pop-culture sensibility with saturated blockings of color. Mace makes her own paper and often punctures her sheets with thread to create colorful, irregular patterns across them. Her works for IMPRINT explore topography and landscape, both through the bold, hard-edged patterns of her methodically produced cyanotypes and with the rough, textured paper that protrudes from the wall, a sort of vertical landscape. And Naranjo Morse’s delicately rendered ink drawings depict ragged stuffed-animal figures amassed in a protest march or wielding threatening weapons—imagery that cuts to the heart of our political moment and reminds us of our own vulnerability.