The evolution of the art of printmaking is practically a human inheritance of knowledge from which we all benefit. We experience printmaking in our daily lives, from the clothes we wear and the books we read to poster advertisements for performances we attend and the money we spend. Printmaking is a three-thousand-year-old art form that reveals within itself an intimacy probably only found in the throes of a fight: gouging, biting, scraping, pressure, scarred surfaces, trenches dug. Years of battling the grain to carve images into wood leave the artists’ hands bent and curved like tree roots, maybe even burned from caustic processes that can scar the hand in the effort of creating visual landscapes.

You could look at the chronology of printmaking as a straight line. However, exploring the art requires leaps back and forwards in time. Discoveries overlap; skills are passed down from teacher to student; techniques are lost and remembered.

We experience printmaking in our daily lives, from the clothes we wear and the books we read to poster advertisements for performances we attend and the money we spend.

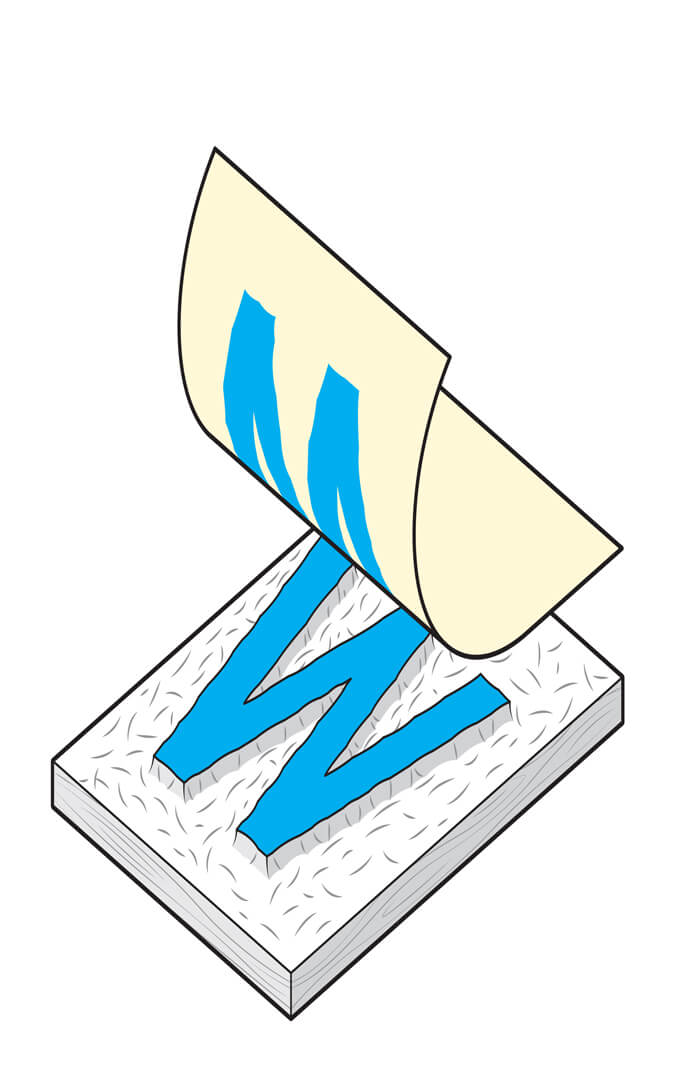

Printmaking was born in the form of Woodblock printing in China around the year 200 AD. This type of printing occurs when a design is carved from a wood block, the raised surface inked, and then put in contact with paper and pressed, creating a print, or stamp. Innovations in printmaking and its refined tools continued in the East, perhaps finding their way to Europe via the Silk Road. This trade route was traveled by Westerners like Katarina Vilioni, daughter of a fourteenth-century family of Italian traders. Her tomb was rediscovered in the southern Chinese town of Yangzhou only sixty-eight years ago.

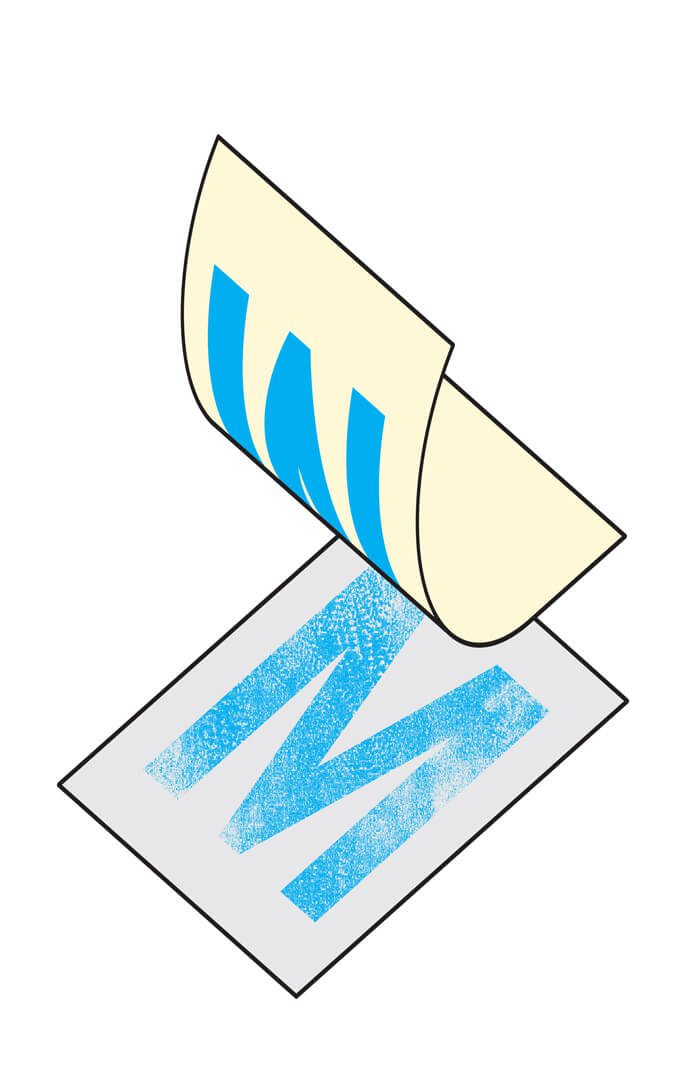

While there is no doubt printmaking is an ancient art, it is also an ever-evolving practice that deepens with knowledge and time. First impressions can be tricky, as discovered by Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione when he invented Monotype. Certainly, the etymology of the phrase comes from this seventeenth-century technique of printing in which only one print can be fully rendered from the design, and all other renderings lose their visual integrity with each print.

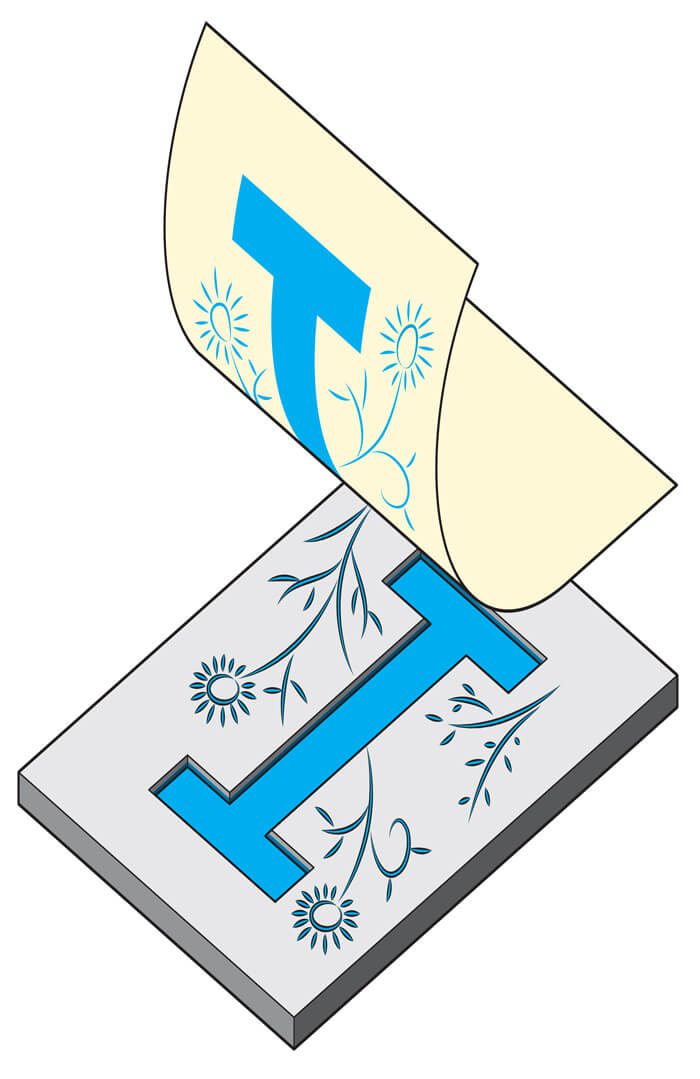

Once an impression is made, printmaking feels immediate. Sometimes, the moment calls you to take a deeper look to flesh out the picture and expand the design—to create test prints and build the art as desired, as you go. Details can be rendered through the Intaglio family of printing, which includes the delicate and deep work of engraving, with or without the dangerous chemical romance of etching. In some ways, intaglio is the opposite of wood cuts. With intaglio, you cut into the surface of a copper or metal plate to create the design. The details can be incredibly fine, with featherlike detail. The ink fills the crevices created by these incising techniques. Some intaglio and engravings leave a “bruise” on the back of the printing, known as embossing.

Three Heads of Women, One Lightly Etched, is an intaglio print by Rembrandt, created towards the end of his life. Two of the women are fully realized, on the verge of telling us their names. The third? A ghost, her eyes as deep as distant galaxies. Her mouth is rendered as if caught by surprise, as though Rembrandt fell asleep with the burin (a tool used to engrave a metal plate) in his hand, the sharp tool gliding across the surface of the plate as he slept, like a wandering skater on thin ice. He used copperplate as one would use a sketch pad today. This print was created shortly before Rembrandt had to sell many of his worldly possessions, including his printing press, to pay his mortgage.

You could look at the chronology of printmaking as a straight line. However, exploring the art requires leaps back and forwards in time. Discoveries overlap; skills are passed down from teacher to student; techniques are lost and remembered.

At the risk of sounding flippant, intaglio is a bit like the tofu of the printmaking world: it’s still intaglio, but it takes on the flavor of the ingredients and instruments used. Also in the intaglio family is Drypoint, created by drawing with a diamond point tool into a plexiglass plate. Once etched, the ink is applied with a series of hand-wiping techniques that result is a delicate quality. Aquatint is an intaglio technique that involves etching but produces areas of tones, rather than lines. Examples are the slate-gray, watercolor-like sadness of Goya’s prints, Kara Walker’s powerful aquatint and etched silhouettes that address race in the U.S., and Mary Cassatt’s aquatint and drypoint (lines etched directly onto a plate, printed with a chemical or mordant treatment). Cassatt’s prints have a sensual dampness to them, like fine paper painted with creamy, watered-down French soap.

Another printmaking technique within the intaglio matrix is the Mezzotint, invented by German solider and amateur engraver Ludwig von Siegen with the assistance of Wallerant Vaillant in 1642. One technique of mezzotint starts in darkness. A copper or steel plate is prepped by roughening the entire surface with a tool that von Siegen invented called the rocker—it resembles a paintbrush with no bristles, just a curved edge you use to rock back and forth across the plate. Rocking is done before detailed etching, meaning that, when it’s time to print, your background would be black, and through etching into the plate, the images are coaxed out of the darkness into the light, like spirits awakened in a psychomanteum. Dutch artist Maurits Cornelis Escher is probably the most-notable printmaker of the mezzotint style, but the heir to this technique is Carol Wax, the American artist who studied the classic techniques and uses them to create rich, saturated prints that elevate the everyday objects she favors, like vintage appliances and abandoned machinery. Through her application of mezzotint, they become mystical.

An uncanny coincidence? The Exposition Universelle of 1889 was a world’s fair held in Paris, from May to October 31. The Eiffel Tower was the grand entrance to the fair, where thirty-five countries were represented. American show-biz legends Buffalo Bill and Annie Oakley were there. Rival inventors Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison were there. Paul Gauguin dragged Vincent van Gogh, who almost certainly didn’t want to deal with the crowds, to the fair. Edvard Munch was also there. It’s very likely that they all saw a particular display, an ancient Peruvian mummy—in fact, Gauguin surely did see it, because he painted this haunting figure several times in his works. The mummy’s legs, drawn into its body, its hands on either side of its shrunken, hollow face. From the mummy’s wide-open mouth, the undeniable expression of a human scream. (Or, maybe this universal scream was about Munch having seen the village nègre, where more than four hundred African people were on display in what was a very popular attraction at the time: a human zoo.) Four years later, Munch recreated the mummy’s horrified gaze, a spirit stranded on a boardwalk near the sea.

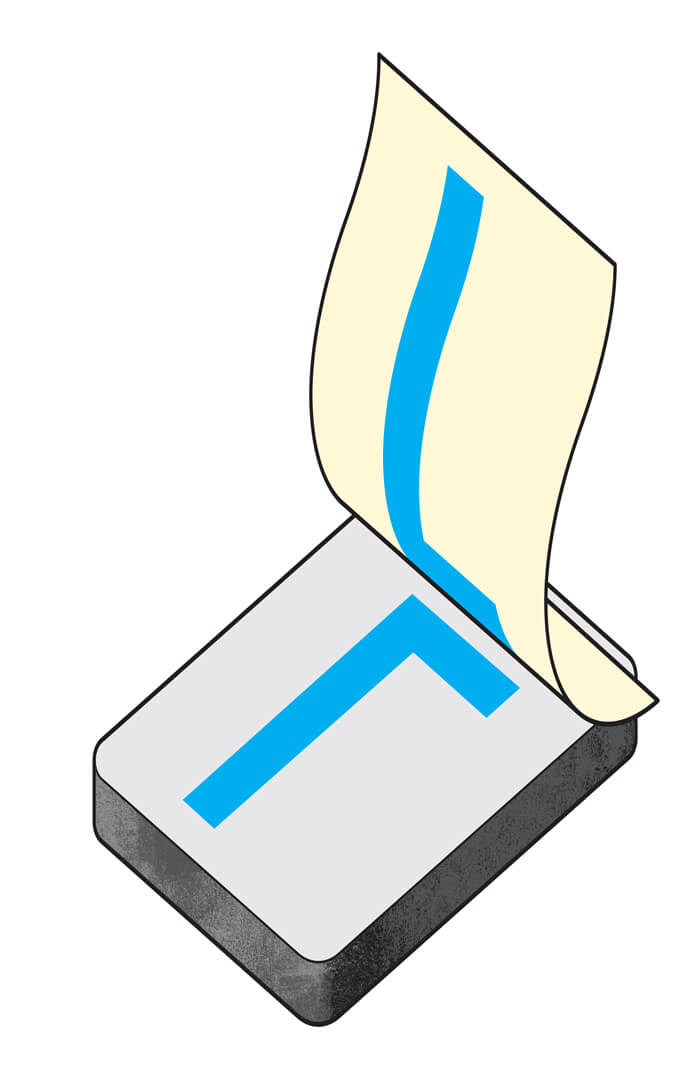

This is one example of a Lithograph—a technique rendering prints from a carved stone, invented in 1796 by the German actor and playwright Alois Senefelder. Unable to maintain the expensive printing techniques for his scripts, he discovered and refined a pretty greasy but ingenious etching technique that uses acid-resistant ink to print on a smooth, fine-grained slab of limestone or metal plate. The image is often drawn right onto the stone with a waxy pen. It’s oil and water in opposition that allows lithography to work. Senefelder basically invented a cheap and easy technique for what would become one of the most popular forms of printmaking, planographic printing, meaning printing on a smooth surface. His oil-and-water technique for printing revolutionized the art form, maybe even to the same degree as moveable type. Sheet music was easily mass-produced, as well as books, and as a result, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s wildly popular posters were plastered on the streets of Paris. In the decades to come, lithography would be used as a tool of war, to stoke the fires of war and resistance, spread propaganda, and sell war bonds. During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Arts Project employed many lithographers to generate posters for all of its departments and projects. The WPA marked the first time black artists had unprecedented access to studios and equipment and were able to be full-time working artists, propelling black visuals to the fore. In 2018, Black Women of Print, a society of black women printers, was founded by Tanekeya Word to form bonds with and highlight the work of intergenerational black women printmakers. It’s a virtual guild where new techniques can develop.

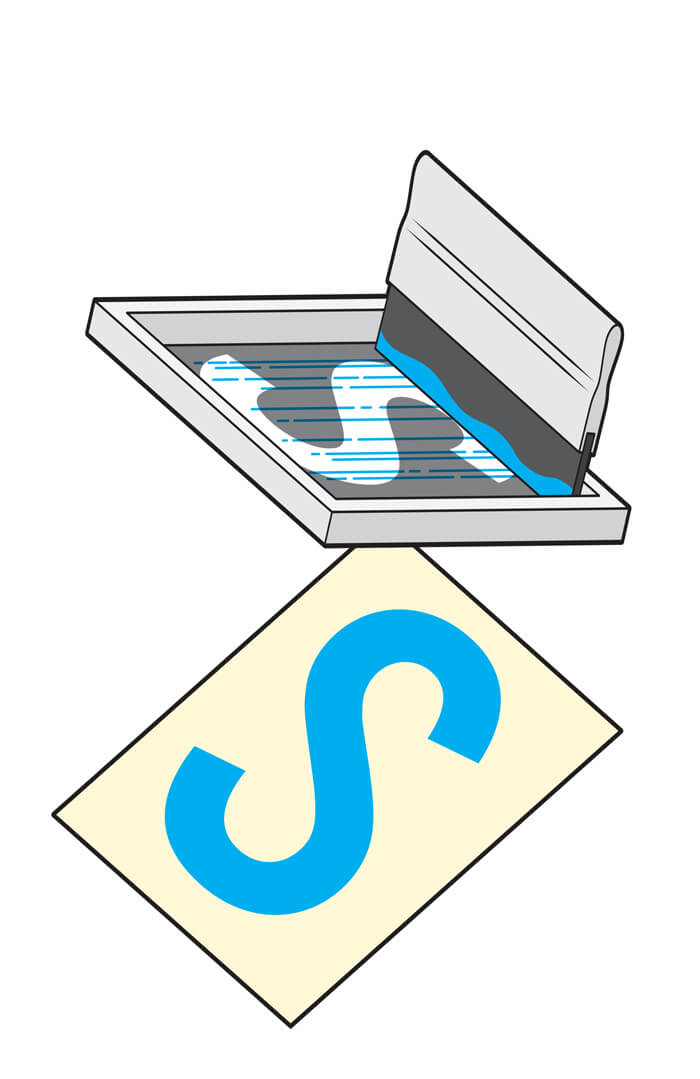

Somewhere along the way, filmmaking and printing met and produced an offspring: Screenprinting. Aside from photocopies, this technique is one of the more familiar to us. A screenprint is made by coating a finely woven screen in emulsion, placing an image or stencil on top of it, and then exposing that image to light. When printing, the part of the stencil or transparency not exposed to the light, is your design. As long as the screen remains intact, an almost infinite number of prints can be pulled from a single design.

We have Andy Warhol to thank for exposing us to screenprinting as a modern pop-culture artform, but perhaps it was Warhol’s favorite silkscreen printer, Alexander Heinrici, who gave the form depth using ink on top of enamel, adding layer upon layer of color. Heinrici calls silkscreening the most painterly and immediate form of printing there is, as it takes fingerspitzengefühl, the feeling you develop in your hands, a knowing through touch. While commonplace, screenprinting retains within its execution the same basic elements of thousands of years of print design.

New Mexico has several places to learn the art of screenprinting—perhaps most notable, Central New Mexico College’s Fuse Makerspace—as well as plenty of unique options for the purchase of fine prints for daily use. In Silver City, Power and Light Press is a full-service, all-female letterpress print shop that makes original cards and other paper goods. Power and Light Press is perhaps best known for their “Stand with Planned Parenthood” tote bag that has contributed nearly one hundred thousand dollars to the nonprofit from a portion of the proceeds. Kei & Molly Textiles, founded in 2010, is an eco-atelier that produces water-based, lower-impact screenprinting on 100% natural fibers—and employs refugees and immigrants. Kei & Molly’s dish towels, napkins, and totes are screenprinted with designs that blend European paper art and Japanese block printing, reflecting the cultural backgrounds of the shop’s owners.

At a certain hour of the day, driving through the streets of Albuquerque, the sun casts shadows so boldly, like a block print. If you’re sitting at a traffic stop, you could almost see the monogram of Albrecht Dürer (who created hundreds of woodcuts and engravings), a shapely letter A enclosing a D. While you’re waiting there, maybe there’s time for his self-portraits to flash across your mind, the processes of printmaking lending an explanation for why a young man would render his own fingers to look arthritic; such are the hands of a prolific engraver who died at fifty-six. On the road ahead of you, streetlights cast sharp shadows where they meet the pavement, the dark and the light a woodcut on the road. The art of printmaking is an invitation to see the magic of life in a new way.