Musician Patrick McGuires writes that while the internet is a proven tool for putting distance between human beings, it’s also been a lifeline for humanity.

After spending the better part of a year feverishly making an album, I felt giddy when Union Hall, a new Denver-based arts non-profit, invited me to specially tailor two nights of performances for their space in 2019. “Do anything you want (within reason) and we’ll cover your costs,” they instructed. “And make sure to take creative risks.” At that point in my music career, I had far more experience than I needed to know that such an offer was exceedingly rare. Typical shows featuring lesser-known artists such as myself are almost always centered more around the selling and consumption of alcohol than anything else, including the music.

If I were to summarize the hundreds of shows I’ve played over a thirteen-year period into a single scene, it would be my now-defunct band finishing the last note of a very loud song to the tepid applause of a bartender and a couple of her patrons on a cold Tuesday night at a midwestern strip mall bar. I’ve been a part of lots of bigger and more exciting shows, but I’ve played so many more like that one that the scene stands up as an accurate representation of my performance experience.

No matter who you are as a musician, what kind of music you make, or how successful you are, forming a true and enduring connection with human beings is what you strive for every time you step foot on a stage. So the opportunity to create two nights of shows in which I could make music, art, and humanity the focus was thrilling to me, especially considering the theme of my album: the internet’s detrimental impact on authentic human intimacy.

It’d be inaccurate to claim that the internet has done nothing but inflict irreparable harm and all-encompassing chaos on the world over the past five years. The #MeToo movement is just one example of the many ways that internet-based technology has helped usher more justice and equity into the world. But during the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, for every positive delivered by Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube, I saw dozens of existential threats caused or made far worse by the internet. The idea of a seemingly harmless algorithm engineered by YouTube amplifying and mutating our worst impulses, spreading and monetizing lies, and helping a comic-book villain like Donald Trump to become President still feels too absurd to be the plot of a science fiction novel, and yet it happened right before our eyes.

After deleting my social media accounts, I lumped all my tech-related angst into my first album as a solo artist and gave it the innocuous title of Charming Pet GIFs. “Let me give you a free piece of advice,” a PR agent I hired to promote the album told me in a deep, salesy voice over the phone. “You can’t be taken seriously as a musician without being on social media. You need to get back on Instagram at the very least.” I declined, released the album in the fall of 2019 to little fanfare, and turned my thoughts to the performances in Denver.

In an instant, the world had flipped, and the human closeness I sought to advocate for with my music had become complicated and dangerous.

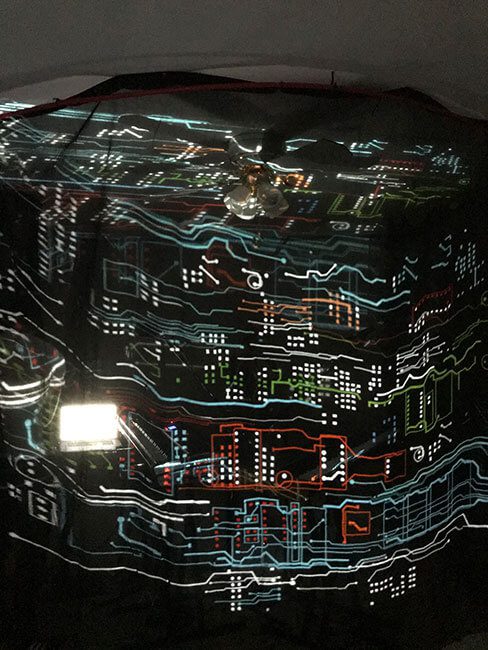

I spent six months collaborating with my fiancée, an artist, and a musician friend who worked as an AV specialist for live events right up until the pandemic obliterated his industry. We had immediately agreed that the audience should check their smartphones at the door in order to fully take in the performance. Backed by a small band, I would perform in the center of the room encased in a cylinder made of scrim fabric on which would be projected lights, graphics, videos, and illustrations. The audience would surround me and the band while a second layer of images would project on the four walls of the room. The shows were scheduled to debut in late March.

But as spring drew closer and news about a mysterious virus started creeping its way into the headlines in early 2020, I prepared for the shows with an increasing premonition that they wouldn’t happen. A week before showtime, my hunch proved correct when the performances were canceled alongside virtually every other public gathering in Colorado and the rest of the United States.

Our vision for these shows was to cram people together in a confined space and drench them in sound and light to get them to feel big, important things they couldn’t experience staring at their phones and laptops. But in an instant, the world had flipped, and the human closeness I sought to advocate for with my music had become complicated and dangerous.

I spent the first few months of lockdown holed up in my house in rural New Mexico, writing as little as I could to get by, and not making music. But one oppressively bright summer day, I found myself recording my second album and filled with the special kind of hope you can only experience by creating something new. While sprawling synthesizers and electronic percussion defined my debut, the album I made during the pandemic was composed almost entirely with acoustic guitars and soft organs.

When I pitched the idea of an acoustic live-stream to the art space in Denver, it seemed more like an admission of defeat than an exciting opportunity to bring music to people and connect with them. After live shows disappeared in the early spring of 2020, countless digital concerts sprang up to stand in their place. Like many frustrated and adrift musicians responding to the pandemic, I viewed live-stream performances as hokey, lightweight substitutions for conventional concerts.

It wasn’t the immersive, risk-taking show we had planned, but it was one of the most human and rewarding performance experiences I’ve ever been a part of.

But a couple of bars into my first song playing in front of the cameras, that feeling changed. I played with the same seriousness and intention of being in the same room with the audience, even though they were scattered across North America and beyond. It wasn’t the immersive, risk-taking show we had planned, but it was one of the most human and rewarding performance experiences I’ve ever been a part of.

Fans and friends later told me that they did feel big, important things while watching the show, and that’s all I can ask for as a songwriter and performer. But, as much as I’d like to, I can’t ignore the crucial role the internet played in making the live-stream possible. COVID-19 has upended our world, and we’re now completely reliant on the internet to stay in contact with people outside our households. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t grateful for it.

The internet has proven to be a powerful tool for putting emotional, philosophical, and physical distance between human beings. But it’s also been a lifeline for humanity during this dark season. Countless ideas, motives, and perspectives play out online, making it a force for both truth and lies, intimacy and warmth as well as aggression and unchecked malice. While technology has kept human beings socially connected, sane, educated, and entertained during the pandemic, it’s also drastically prolonged the crisis by politicizing safeguards like masks and efficiently spreading misinformation that has gotten people killed. I desperately, and foolishly, want things to be defined either as clearly good or bad. But because the internet is a representation of human beings and their actions, it will always be a frustratingly complex combination of both.