An experiment in non-traditional exhibition spaces, the High Desert Art Fair breaks down the boundary between the gallery and the home, creating a radically immersive context for experiencing art.

FLAMINGO HEIGHTS, CA—Odds are, if you’ve seen one art fair, you’ve seen them all. Seemingly endless hordes of fairgoers navigating similarly endless rows of hastily constructed, thematically indistinguishable “white cubes.” Regardless of where any given fair happens to be held, this is essentially what you can expect. The artworks are often unoriginal. The sandwiches are always overpriced. As someone who attends a lot of these throughout the year, let’s just say: they get old.

For this reason, I was intrigued when I first heard about the High Desert Art Fair in Flamingo Heights, California, a weekend-long event on February 24-25, 2024, that promised to be an “immersive art viewing experience, bringing art communities to non-traditional exhibition spaces.” Even more exciting to me was a quote from the fair’s organizer, Nicholas Fahey, who declared: “Art is not meant for only showing and selling. It’s for sharing, for connecting, and for storytelling.” Desperate for a breath of fresh air, I RSVP’d.

Climbing the old winding road jutting north of Yucca Valley on the morning of the first day—past the scattered, multi-million dollar homes of the Western Hills Estates that overlook Pipes Wash, where the horizon opens up to the sprawling high desert—I was delighted to pull into the driveway of a humble, single-family home. No volunteers in yellow vests. No parking fee. No lines. I was late, so I slipped through the front door to catch the tail end of legendary British documentary photographer Janette Beckman’s talk.

“One thing I learned at the very beginning of my career was to always have my camera ready,” she told the small crowd that had gathered in the living room. Standing before her iconic portrait of American rapper Slick Rick, she continued: “When he walked into my studio in 1989, the first thing he did was find his mark, drop his bag, and grab his crotch. Luckily, I had my camera ready, so I snapped.”

She went on to tell the stories behind the portraits that would come to define her career, including those of LL Cool J, Salt-N-Pepa, and Debbie Harry, describing the ways her approach to photography has and hasn’t changed throughout her illustrious career. On the wall behind her, above the fireplace, in the hallway by the bathroom, near the window in the kitchen—in every nook and cranny of the cozy, adobe-themed house, Beckman’s most famous photographs proudly hung.

After a short break, we all shuffled to the guest house in the backyard, where the Los Angeles– and New York City–based photographer Blaise Cepis sat uncomfortably on the edge of a coral-pink bed.

“I have the curse of starting in advertising and then making art later on,” he told the group that had huddled into the room. While I leaned on a dresser, several people had found a spot on the floor to sit and listen. It was cramped, to be sure, but it all felt refreshingly informal.

When asked whether his approach to art was very different from his approach to commercial work, he said, “Even in my personal work, I never really stray from the brief. And yet, there is nothing more exciting to me than having a few drinks with friends and making something really strange—something that has nothing to do with the ‘Royal Caribbean’ campaign I’ve been working on all day.” As odd as it was at first, something was humanizing about attending an artist talk in someone’s bedroom.

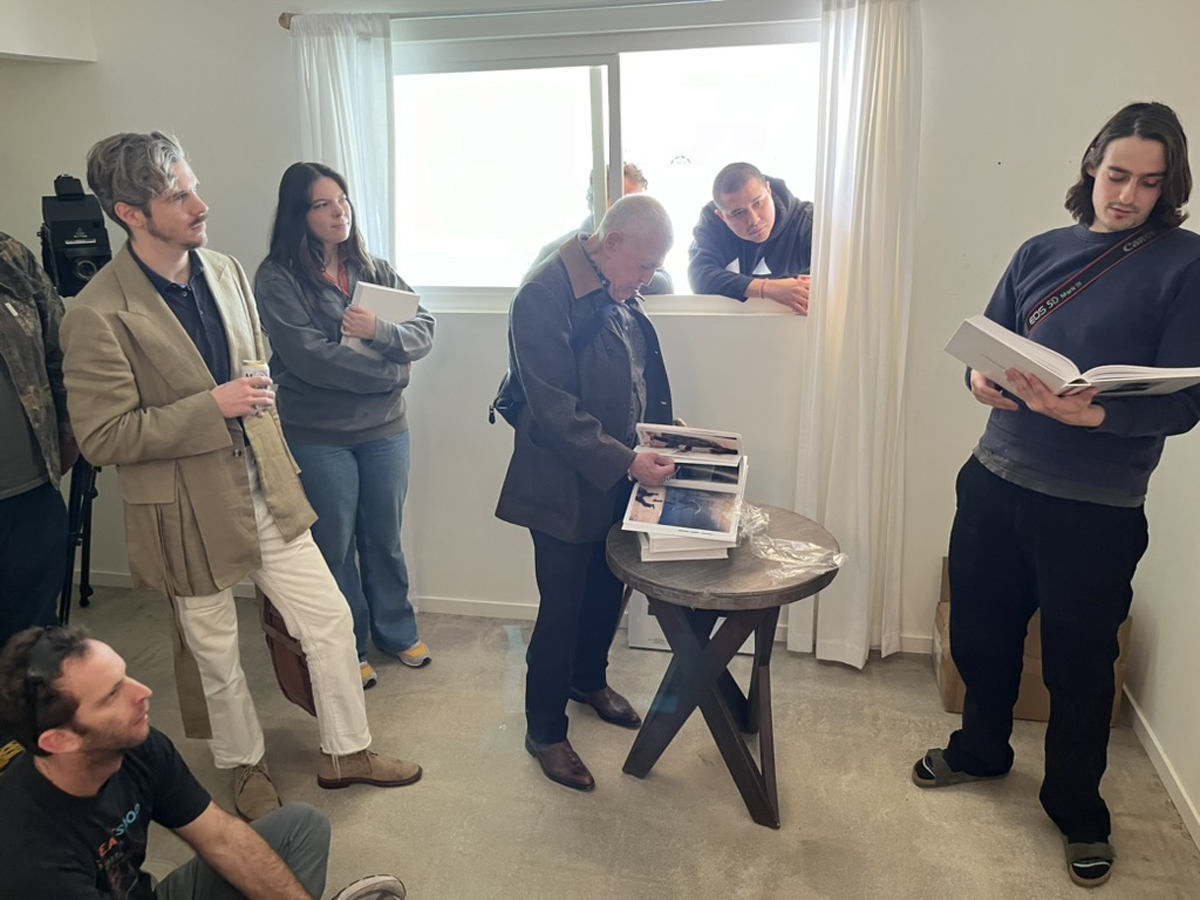

In an even smaller room on the “other side of town” (i.e. barely three minutes by car), standing only a few feet from up-and-coming documentary photographer Jacob Messex, I watched him flip through the pages of his new book, Euthanasia (2024).

“A lot of these scenes are happy accidents,” Messex said. “After I got my first camera, I carried it everywhere I went, took photos of moments that felt cinematic. I wasn’t really doing anything on purpose back then.”

Both figuratively and literally, these intimate experiences closed the gap between the artist and the viewer in a way I’ve never seen before. Though each of the five galleries attending the fair interpreted “non-traditional exhibition space” differently—with W(AN)T Studio’s space appearing to be the most formally curated, while Momentum’s felt the most casual—every event left me feeling like I had experienced something real.

In their golden years—which, in my mind, ended well before the pandemic—this was the principal appeal of art fairs. Regardless of your status in the art world, all fairgoers were offered the same exhilarating opportunity to rub shoulders with renowned gallerists, collectors, curators, and the like. Somehow, the oversaturated, post-pandemic art marketplace seems to have lost sight of the importance of this experience. According to co-founder of Independent New York, Elizabeth Dee, the best term to describe this problem is “context collapse.”

“For the last half-century or more, galleries played a key role in creating contexts for contemporary art outside of the artist’s studio,” Dee wrote in an article for artnet. “The context for the reception of an artist’s work, especially the work of an artist at the beginning of a career, was formed in large part by the gallery.”

As art fair-type events expanded, proliferated, and became heavily commercialized, these spaces lost the ability to encourage authentic experiences with art. As if, at the same rate that the number of galleries in attendance grew, the possibility for each individual cube to provide a thoughtful and purposeful context for the works on view evaporated.

Dee continued, “Seeing art alongside various other works from an artist’s studio that evince a sustained investigation or practice over time, or works by several artists that share common ideas and interests, and feed each other’s art”—this is at least part of what has been lost.

While I’m sure this first installment of Fahey’s High Desert Art Fair presented several kinks that later versions will need to work out, drifting from bedside artist talk to “Cocktails and Bites” event to “Listening Party” to “Video Art Presentation” and back to my hotel was, to my surprise, pretty effortless. I was exhausted by the end, to be sure; but it wasn’t because I had just spent eight mind-numbing hours overstimulated and underfed. Instead, I’d spent that time meandering through people’s homes, surprised at how much I enjoyed viewing art in that setting; meeting new people around kitchen tables; eavesdropping on poolside conversations between celebrated artists.

For once, I was offered time, space, and context to soak in new ideas. And, for once, I’m excited to go back.