Harwood Museum of Art has lived multiple lives as library, artist crash pad, and world-class art center. The Taos cultural gem now celebrates its centennial.

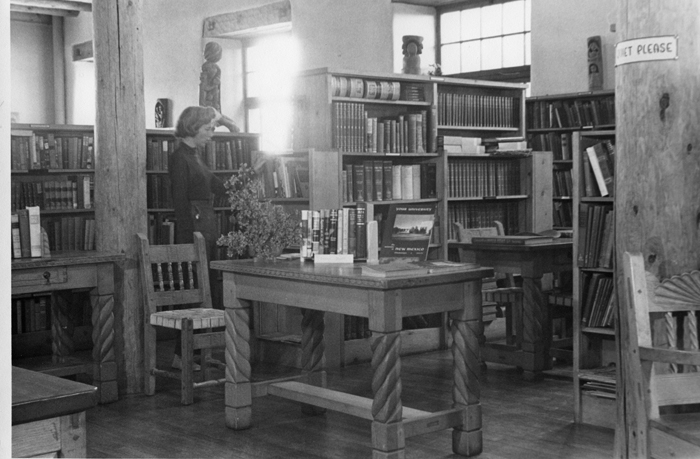

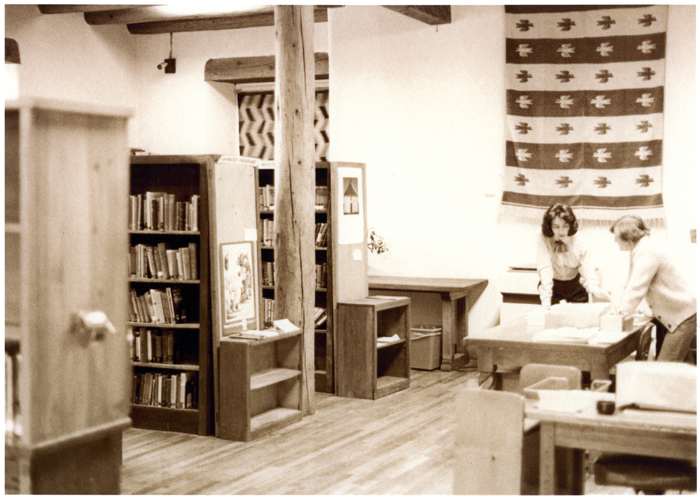

Approximately one hundred years ago, before the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico, became a well-known arts destination—one that’s outfitted with the meditative Agnes Martin Gallery—the modest adobe building on Ledoux Street was the town’s only library, and perhaps the region’s most unusual.

“Lucy Harwood would put books on her front porch and people would come by and read and she would serve them lemonade,” says Nicole Dial-Kay, the Harwood’s curator of exhibitions and collections.

“Mabel Dodge Luhan came [to Taos] shortly after. She also had this incredible collection of books and was friends with so many authors and poets and psychoanalysts and all of these writers,” continues Dial-Kay. “Mabel had a relationship with the only female-run bookstore in New York and they sent books to Taos every month, and so this enormous library gets started. It became this incredibly rare, super valuable collection in Taos that everyone had access to.”

Juniper Leherissey, Harwood Museum of Art executive director, grew up inside the entrancing, community-centric library that would eventually morph into a decorated steward of Western and American art.

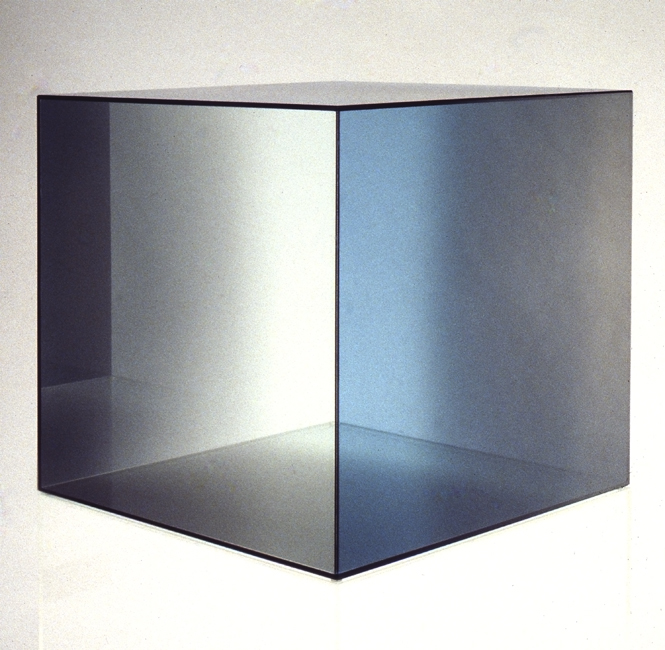

“I would go to the library every day after school to read or do homework,” says Leherissey. “When I came back from college one time, it was no longer a library. I go upstairs and there’s a Chuck Close portrait of Agnes Martin and also a [Richard] Diebenkorn. I said to myself, ‘How did this happen?’” Leherissey was seeing the old library transform into an extraordinary art center in real time.

“I basically came back to my hometown, and now I’m working in this museum that I love in the library I grew up in,” says Leherissey about the education center, museum, and regional linchpin that still exudes an open-armed spirit. “The Harwood’s been one of the cultural anchors in Taos where the public has been invited, even when it was a personal home. There’s something that has always been community centric.”

In June 2023, the Harwood kicks off a centennial anniversary celebration that includes a comprehensive seven-month-plus Harwood history exhibition that will fill all nine galleries of the museum, which has more than 6,500 permanent objects by nearly 800 artists in its collection. The show, which will display deep cuts such as Works Progress Administration furniture restored by admired New Mexico santero Luis Tapia, will also partially recreate the public library.

The 100-year anniversary includes a brand-new illustrated companion publication that documents and retells the Harwood’s rich history with a decolonial emphasis. Additionally, there will be three instances of “Open Wall,” a Harwood concept from the 1940s that allows any Taos County resident to hang artwork at the museum.

Moving forward, the state’s second-oldest museum and regional cultural anchor located on traditional unceded Indigenous lands, is focused on integrating local Native American and Hispanic cultures, narratives, and histories into its practices. As part of the Harwood 100 initiative, the museum commissioned Lynnette Haozous (Chiricahua Apache, Diné, Taos Pueblo), also one of Southwest Contemporary’s 2023 12 New Mexico Artists to Know Now, to create an original work of art at the Harwood under the theme “Envisioning the Future.” The site-specific mural Seeds of the Future asserts agency, autonomy, and self-representation of Taos Pueblo people and will depict three young Taos Pueblo women and a baby “spending time together and looking after the next generation—ensuring the future.”

Burt and Lucy Harwood—who, along with future Taos Society of Artists painters, were enmeshed in Paris, France’s expat art migration—moved from France to Taos in December 1916 and purchased a modest adobe home on Ledoux Street just off the Taos Plaza.

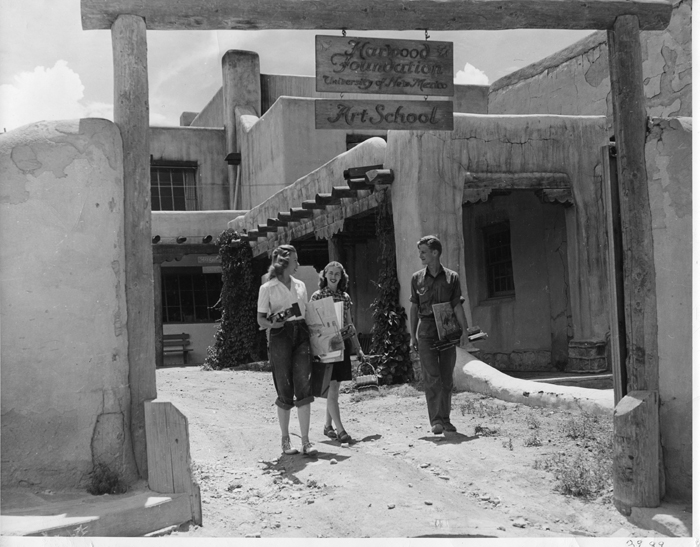

The property, dubbed El Pueblito following significant Pueblo-Spanish Revival architectural remodels and additions, became a counterculture hangout spot and crash pad for Taos Society of Artists members and other modernist Taos artists. The former group, often called the first professional artists’ association in the Southwest, was founded the year before the Harwoods arrived in Northern New Mexico.

For three days immediately following Burt Harwood’s September 1922 death, Lucy Harwood opened her studio to exhibit her late husband’s work to the public. The next year, she started the Harwood Foundation with a group that included Victor Higgins and Bert Phillips of the Taos Society of Artists.

According to Harwood Centennial: 100 Works for 100 Years (Museum of New Mexico Press) by Dial-Kay and Harwood associate curator Emily Santhanam, the mission of the Harwood Foundation, scrawled on Harwood stationery, was simple:

Activities:

Art

History

Library

There have been numerous tenants at the Harwood since the foundation’s 1923 establishment. The UNM Summer Field School of Art, which taught liberal arts, sciences, literature, and teacher training to students such as Earl Stroh and Agnes Martin, set up shop on Ledoux from 1929 to 1956.

There have also been numerous building expansions and overhauls, including a new wing designed and completed in 1938 by John Gaw Meem, who is known in New Mexico for designing Zimmerman Library on the University of New Mexico’s main Albuquerque campus and contributing an addition to Santa Fe hotel La Fonda on the Plaza.

Decades later, the Taos public library officially outgrew its space at the Harwood and moved to its current location on Camino de la Placita in 1996. Robert M. Ellis was then brought out of retirement to transform the Harwood space—which is currently on the National Register of Historic Places roster—into a world-class arts center.

Ellis, the former director of the UNM Art Museum and Jonson Gallery, acquired seven later paintings by American abstract expressionist Agnes Martin—the two ate lunch together weekly after Martin moved back to the region—to create a standalone gallery that’s been compared to Houston’s Rothko Chapel. The museum, which opened to the public in 1997 and is now a two-story house and museum space, is also outfitted with additional gallery spaces that have exhibited pieces by big-name artists in the Western and contemporary art canon, including artists with New Mexico ties, such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation), Tony Abeyta (Navajo), and Gustavo Victor Goler.

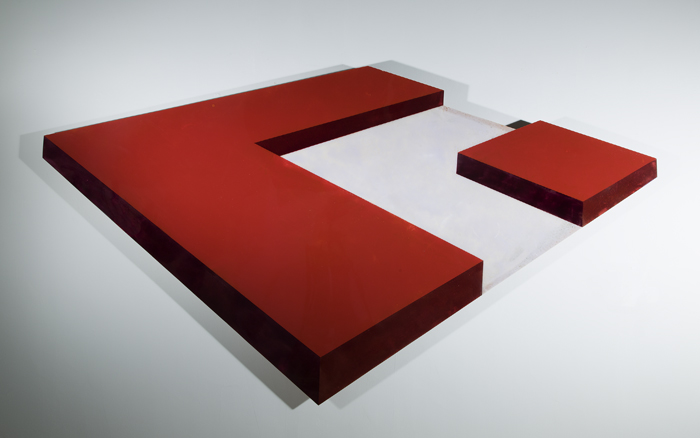

The sweeping exhibition Harwood Museum of Art Centennial, scheduled to take place June 3, 2023 through January 28, 2024, offers first-time and rare opportunities to see works by legends. The show of more than 200 artworks includes pieces by Ernest Blumenschein and Georgia O’Keeffe’s 1929 painting The Lawrence Tree. Works on loan by Ansel Adams, Margaret Bourke-White, Elaine de Kooning, and Paul Strand will also be exhibited.

The recreated library will include more than 200 books, many of them on loan from the UNM Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections. The public can enjoy a return to the old library days of the Harwood by perusing the library installation.

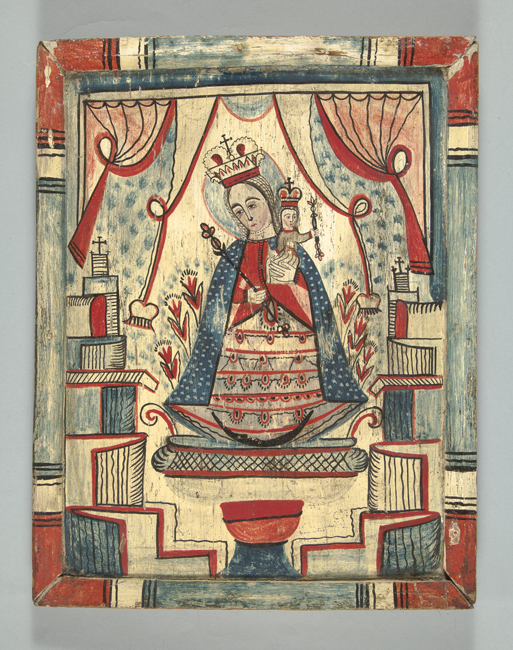

Overall, the Harwood’s collection includes Spanish Colonial and contemporary devotional art, 1920s and 1930s work from the Taos Society of Artists, Works Progress Administration furniture and tinwork, post–World War II art from the Taos Moderns, pieces by LA artists who flocked to Taos from the 1960s to 1990s, work by notable 20th- and 21st-century Native American artists, and art by living New Mexicans.

The museum is also making efforts to both decolonize the museum and show unique work.

Harwood Museum of Art Centennial will display eleven pieces of WPA-era furniture restored by Luis Tapia, a Santa Fe santero who was recently recognized by the National Endowment for the Arts as a 2023 National Heritage Fellow, one of the nation’s highest honors in the folk and traditional arts. The Harwood’s extensive collection of WPA works includes pieces by modernist santero Patrociño Barela and Spanish Colonial carver Máximo “Max” L. Luna.

“We really tried to look at the Hispanic furniture tradition that probably was pushed aside more as a craft aspect of our history instead of fine art,” says Dial-Kay.

Harwood leadership says they’re constantly reexamining the museum’s Eurocentric past and approaches, and that more pivoting needs to be done.

“For 100 years, we, like most museums, have shown the products of our founders,” Dial-Kay explains. “We know museums are inherently colonial institutions. Our museum was founded by European individuals that were looking for a space to show and promote their art, and our collection and our exhibition history reflect that. It’s not what our New Mexican community looks like, which is a huge problem.”

“We’re really trying to unearth the narratives that maybe weren’t so obvious in our exhibition history or collecting practices,” says Dial-Kay, who says that the museum is close to finalizing its 2024 through 2026 exhibition schedule and it’s “looking really different than the last 100 years. It’s time. It’s necessary.”

“Most of the artists [in future exhibitions] are artists of color. We’re making spaces for territorial voices that come from different communities,” she adds. “We’re relying a lot more on community input for exhibition ideas and artists.”

The Harwood sits on occupied lands that are the traditional ancestral home of Taos Pueblo, the original inhabitants of the territory, as well as the Diné/Navajo, Ute, Jicarilla Apache, Kiowa, and Comanche peoples. Dial-Kay says that the Harwood has a ninety-nine-year agreement with Taos Pueblo to safekeep their archives until the Pueblo can create their own museum space.

“The exhibition has an extensive feature on the land history and the role many of our heroes played in it, including Lucy Harwood,” explains Dial-Kay. “We found documents in which she asked [Franklin Delano Roosevelt] to quiet the Pueblo title to our land so that it would be officially hers without any land claims against her. That’s a hard pill to swallow. We’re definitely reckoning with some of the injustices of our past in the show.”

“Our Taos art story, our written-down art history, and our collection is still predominantly a white story,” adds Leherissey, who was the Harwood development director for eight years before becoming museum director in 2019. “We maybe pulled away from the community a little bit in becoming a museum, and I think that this is particularly a time to reassess who we are.

“We’ve made it to 100 years and we’re not going anywhere… but coming from this community, I know that the previous 100 years is a myopic perspective of our history, so how do we really acknowledge the biases of the past? How can we be a leader, not just for the Harwood but for the community? It’s going to be a process,” says Leherissey.

The centennial kick-off is scheduled to take place Friday, June 2, and Saturday, June 3, 2023, at the Harwood Museum of Art at 238 Ledoux Street in Taos. The Harwood 100 Birthday Bash is slated two weekends later on Friday, June 16, at the Sagebrush Events Center, and will include Taos Pueblo’s Hail Creek Singers, mariachi group Lorenzo Martin Trio, and dance music by Big Swing Theory. Other Harwood and centennial-related programming can be found by visiting harwoodmuseum.org.