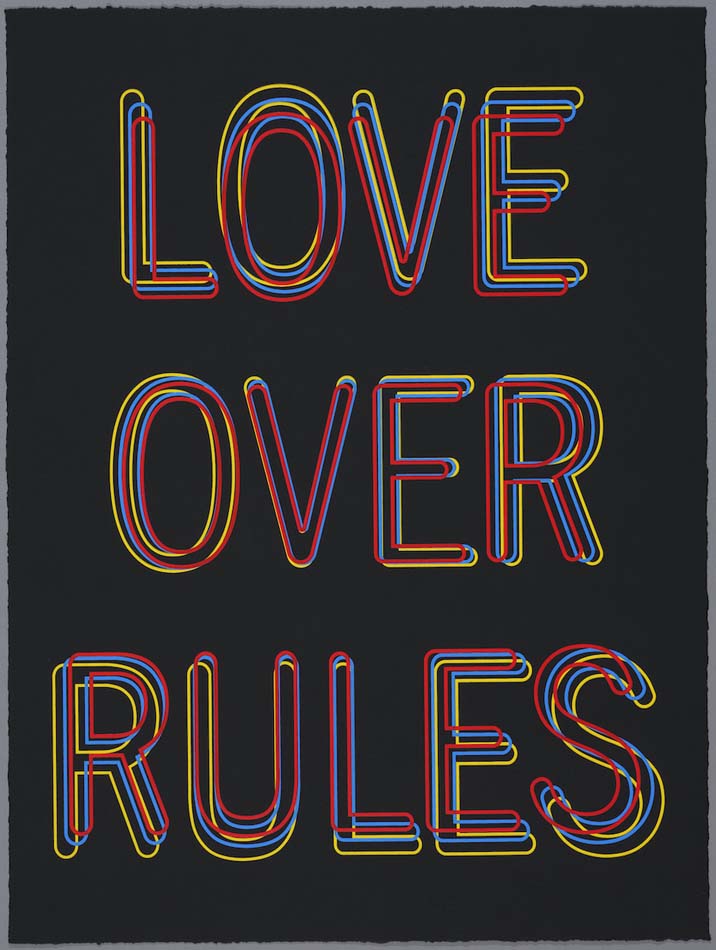

Hank Willis Thomas’s LOVERULES offers a comprehensive survey of a decade’s worth of artwork but flounders in our current political crisis.

LOVERULES—From the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation

January 18–June 21, 2025

University of Arizona Museum of Art, Tucson

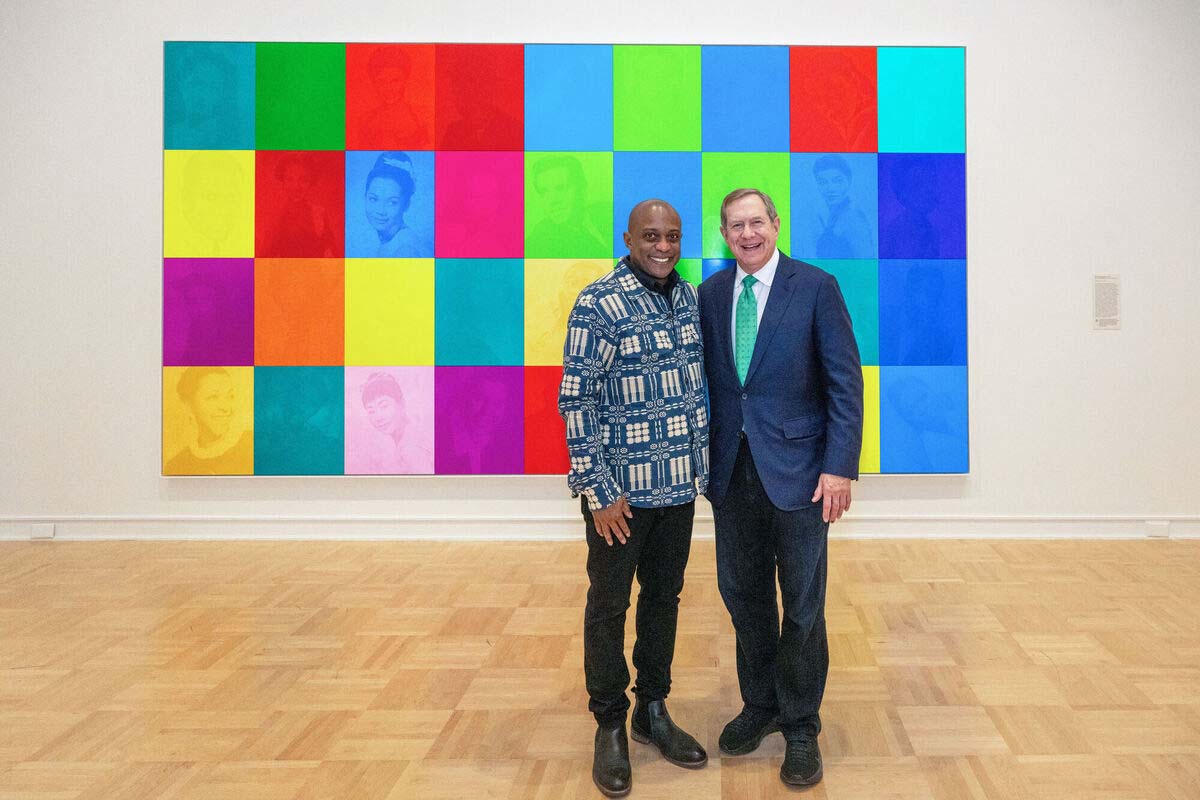

“There are so many wonderful places in Tucson, like the University of Arizona,” said Jordan B. Schnitzer, a prominent West Coast art collector, philanthropist, and real estate baron who stood before a crowd at the opening event for Hank Willis Thomas: LOVERULES installed at the Museum of Art on campus. “So many wonderful places, like Raytheon.”

Like Raytheon, whose Missiles and Defense division is headquartered in Tucson, and whose longstanding defense contracts result in innocent deaths overseas, Schnitzer owns and invests by way of Schnitzer Properties—an investment portfolio that includes 33 million square feet in six states in the U.S. West. This includes industrial warehouse space that serves Sun Corridor Inc., an economic development organization, of which Raytheon shares a major portion.

Schnitzer introduced Hank Willis Thomas as his friend as they stood on either side of All Things Being Equal (2010), the phrase itself cut out of mirrored surfaces and affixed on the wall between them.

From the jump, Thomas’s has work has pushed reform—not radical liberation—with a Democratic drive that at first suited a neoliberal and centrist public who faced discomfort during Trump’s first administration. In the face of our current moment—of genocide and mass deportation, just for two examples—Thomas’s concepts flounder in the rising tide of our current political crisis.

LOVERULES: From the Collections of Jordan B. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation seems to have been organized for an alternative future where Kamala Harris won the presidential election, where maxims from 2016 ring true, and where places like Raytheon can fly under the radar without journalists, activists, and TikTok reminding us just where the weapons blowing up neighborhoods in Gaza come from.

The curation at UAMA focuses on greatest hits, which Schnitzer has collected for two decades, from 2002 to 2022. The included works cannot and do not meet us in 2025, bringing into question Thomas’s ongoing relevance and depth of political inquiry. Platitudes and symbols without deeper context serve to assuage tired generations who cannot see past their own neoliberalism.

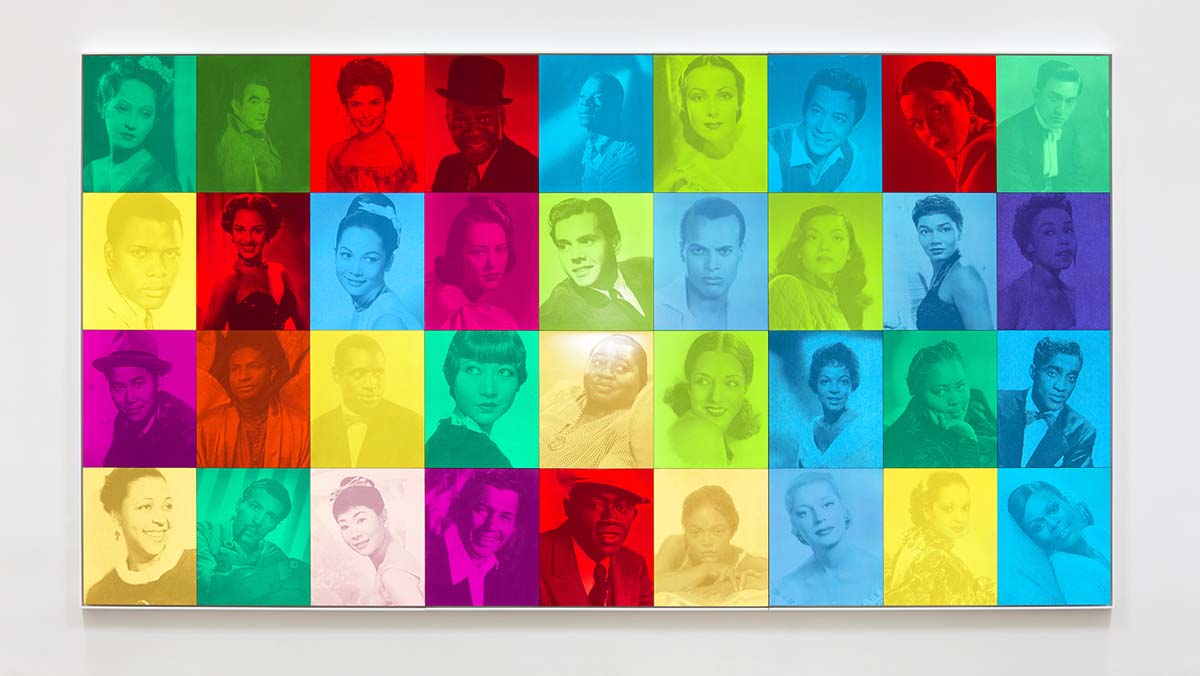

Schnitzer seems to have collected Thomas’s most anodyne works on race and gender, including a significant portion of his Unbranded: Branded and Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America series, and many of his flag sculptures. Another installation features a wall of UV-printed portraits of leaders, celebrities, and titans of color that are only visible through flash photography, where the images become clearer as an image on your phone.

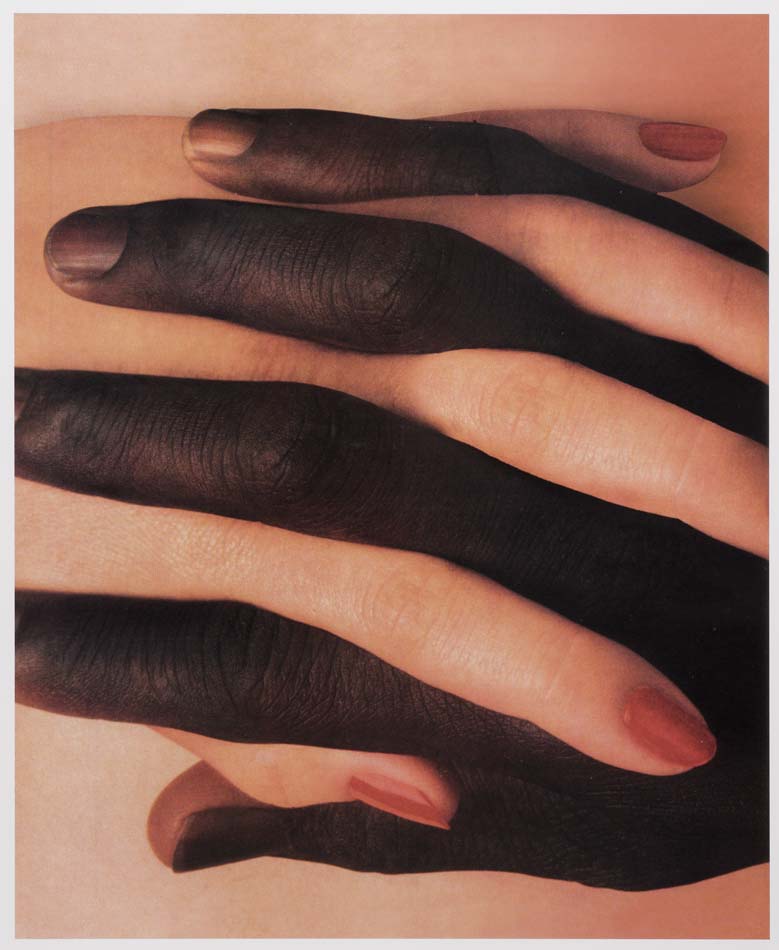

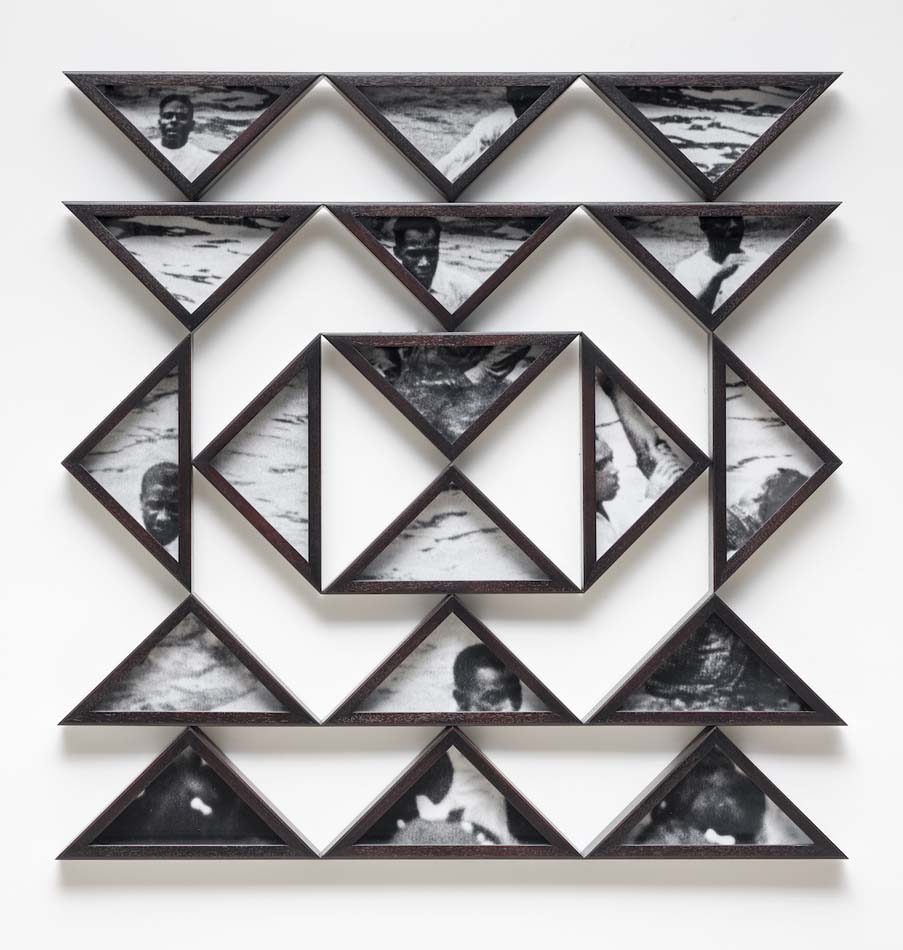

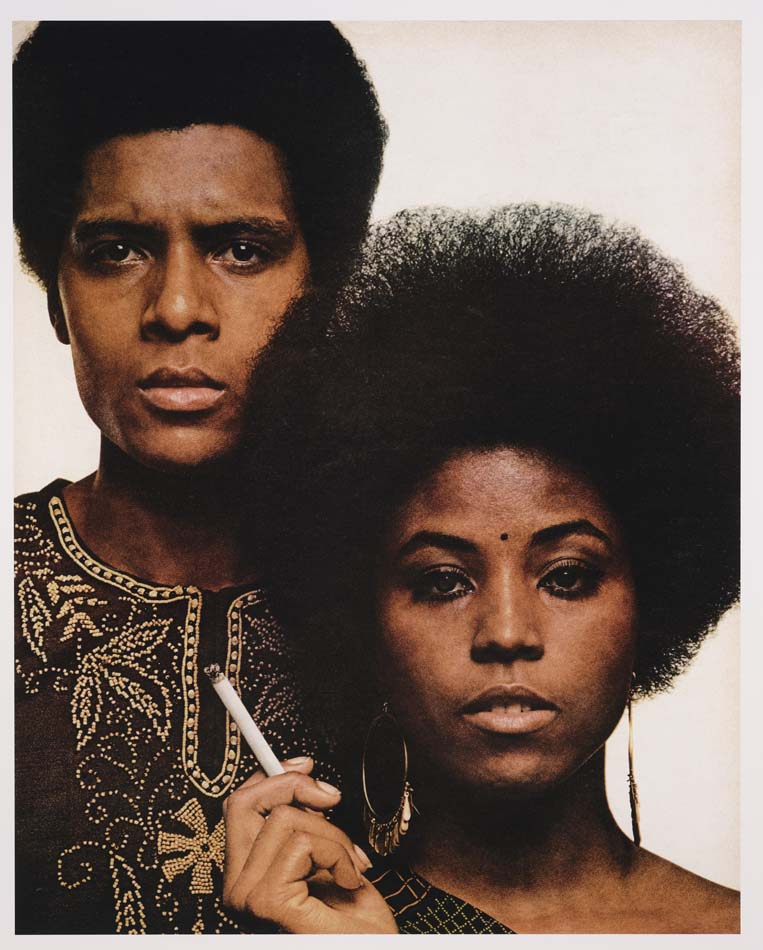

Thomas’s more critical work is his earliest: in his Unbranded series, Thomas collected and removed advertising elements like copywriting, slogans, and logos from a spectrum of magazine ads featuring Black individuals.

Farewell Uncle Tom (1971/2007), for example—a digital chromogenic print of a Black woman and man, side by side, him in an embroidered dashiki, her with an afro and a cigarette—evokes a radical chic idea of the Black Panthers and of Blackness in the 1960s as envisioned by a marketing executive, perhaps if they smoked a certain brand of cigarette. The remaining portrait, though striking without the advertisement context, still dilutes the reality of Black radical struggle. What’s missing is a history of leaders who were disappeared; this image of two models is instead left in their absence.

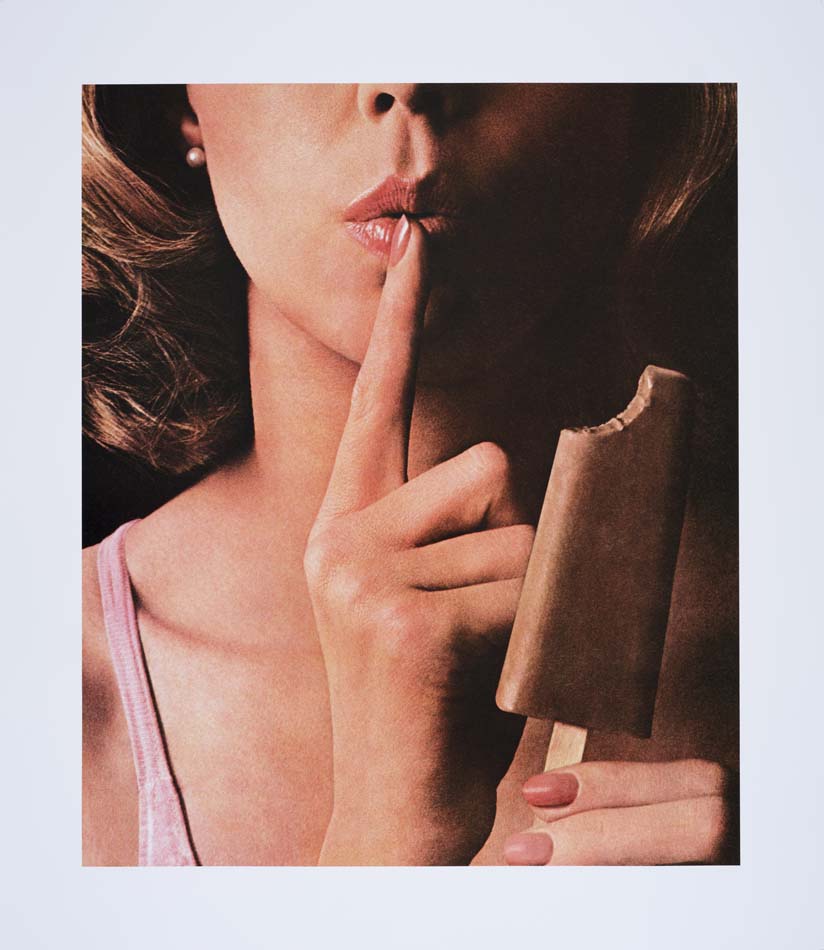

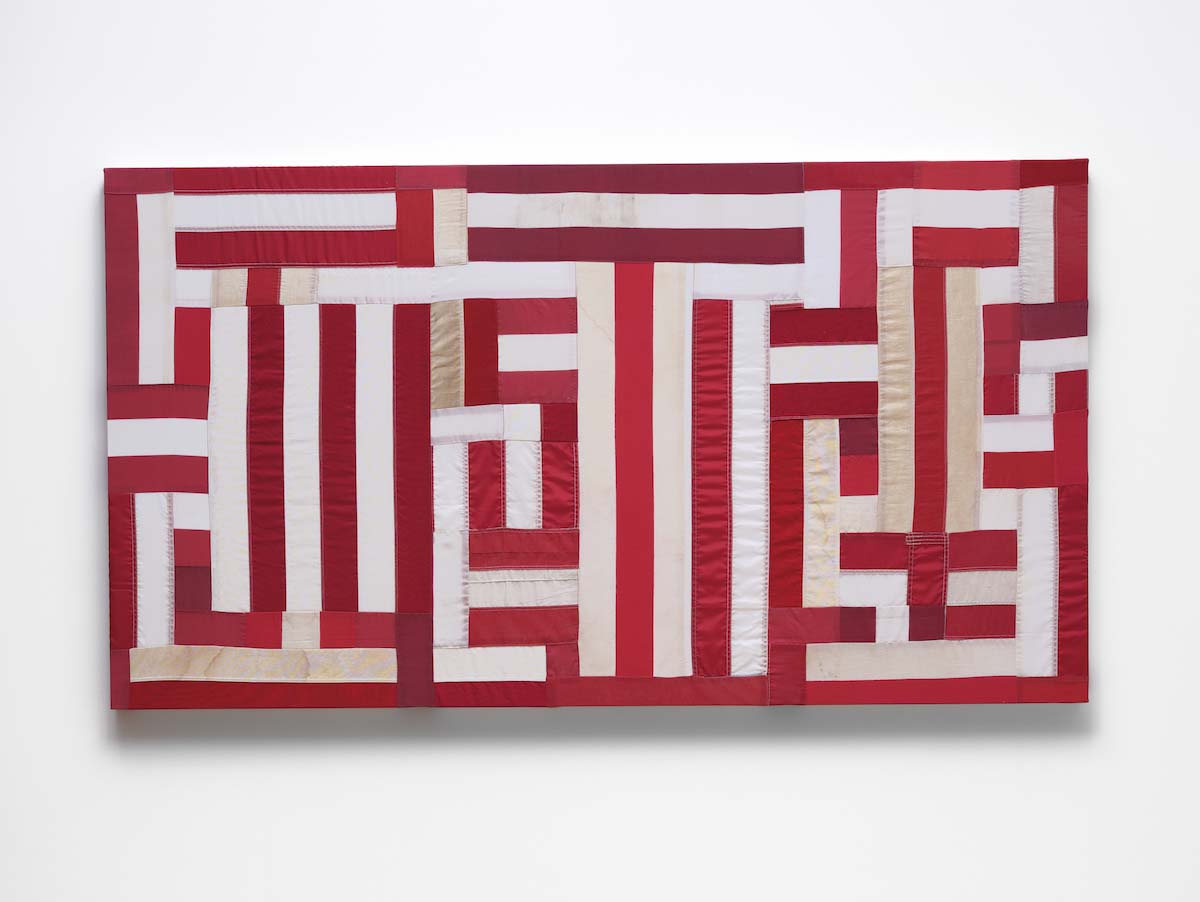

An entire room is dedicated to Unbranded: A Century of White Women, in which Thomas sifted through and selected advertisements from every year between 1915 and 2015 featuring white femininity in order to explicate pop cultural attitudes towards white women. Nearly every ad alludes to casual violence, subjugation, or sexualization—a woman in a prison uniform chained to her refrigerator, another close up of a woman smoking a cigarette hovering near and below a man’s belt while looking up—situations where power is stripped by gender, but whose activities and postures would translate much differently for a person of color. White women are perfect victims and mannequins equally.

Only a handful of images show white femmes alongside Black figures who are either waiting on or serving these white women, which the wall text describes as “pointing to the often fraught shared fight for liberation.” It’s like the Olympia’s Maid of advertising—where women are forced to team together under the white male gaze.

Whatever visual elements that held the ad together—like copywriting or logos— have been erased. In their place remain oppressive and abiding attitudes about gender and race, with desires presented (sexualized cigarettes and pantyhose, racially fraught coffee) then stultified. There is nothing to buy here but a vision of the world, reframed for an audience encouraged to wonder about their position in it without any guidance. Thomas’s concepts are clear and democratic, but toothless in their failure to indict or even lead his audience.

Removal is a political act, a means to control a narrative. On one end of the spectrum, removal is an act of violent erasure (DEI, trans identity), physical removals (of the unhoused, of Palestinians and other refugees, immigrants, and those ICE deems un-American), disappearing, and death.

On the other, it is an act of political empowerment, where absence reframes a storyline and representation. Thomas tells morality tales through the visual language of advertising and tricks of the eye, lenticulars, and mirrored surfaces.

In 15,580 (2017) (2018), an outsized U.S. flag with only white stars on navy blue fabric, the pole drilled high into the gallery wall, drapes and drags across the floor in a cascade of stars. Thomas is collectible: this version, among many, is pulled from a series of flags Thomas has made in dedication to thousands of lives lost on a yearly basis to gun violence in the U.S. Each starry flag is an archive kept for the number of gun deaths per year.

“Artists are chroniclers of our times; Hank puts these issues in front of us again to work through our thoughts,” said Schnitzer during a hosted conversation between himself and the artist. Later, he quipped that you could either go to therapy or you could go to the museum. He chose the museum.

I imagine Schnitzer working through his thoughts, looking at a Thomas sculpture. I believe this work was made for him: pop cultural reliquaries for white guilt. Later, during the artist lecture, I watched as Thomas told a crowd of aging, mostly white Arizonans that they were their ancestors’ wildest dreams.

Thomas’s work emanates a basic empathy but rarely confronts the viewer. It’s a populist vision: a kind of Norman Rockwell for the Trump era. “You can’t be sincere when you’re trying to be relevant,” said Thomas. It seems for Thomas, relevancy, or rather, any attempt at addressing political realities, is at odds with sincerity—a sentiment that rings more discordant than harmonious.