The For Freedoms collective, dubbed the country’s largest network of artists, cultural workers, and organizations, engages in tough and important conversations about social change through artistic civic activism.

This article is part of our Collectivity + Collaboration series, a continuation of the ideas explored in Southwest Contemporary Vol. 5.

SALT LAKE CITY, UT AND ALBUQUERQUE, NM—This country has arguably been behind separate barricades for far too long, mired in politicization that puts people on guard—and on edge.

Instead of a rigid view of and reaction to the political climate of the United States, the For Freedoms collective creates civic engagement projects that disarm. It formed during the lead-up to the 2016 general election and has since expanded its network into what the group calls the country’s largest community of artists, cultural workers, and organizations.

“When you call something political, people automatically want to take a side and a position and walls go up, but if you call something art, it automatically sparks curiosity,” says Michelle Woo, one of four founding members of For Freedoms. “Because of the inherently subjective nature of art and the creative nature of art, we provide people multiple entry points into a conversation in which they might not otherwise feel they belong.”

The group encourages non-partisan civic engagement participation—ranging from a nationwide artist-made billboard project to youth and adult literacy programs—that fall in line with the conversation and creativity tenets of For Freedoms, whose name was inspired by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union address. Documentation and a celebration of For Freedoms’s multi-pronged achievements are currently on display at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art, a Salt Lake City museum that is redefining the boundaries of art in a historically conservative state.

Woo, Hank Willis Thomas, Eric Gottesman, and Wyatt Gallery formed the anti-partisan arts and civic engagement organization because they weren’t fans of the fissure that had opened in the country.

“We thought that people were no longer talking to each other and conversations were being dumbed down to repetitive, nonsensical talking points,” says Woo, who’s currently based in Los Angeles. “As artists, we thought, ‘What inspires us to dig deeper? What provides more entry points into a topic and issue?’

“Art is inherently subjective [and] requires us to pause and take stock of what we’re looking at and what we’re experiencing,” she continues. “I think the way that we consume media and information doesn’t promote that kind of nuanced engagement or literacy so we wanted to bring that back into the fold.”

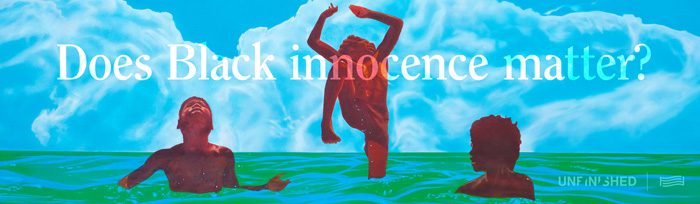

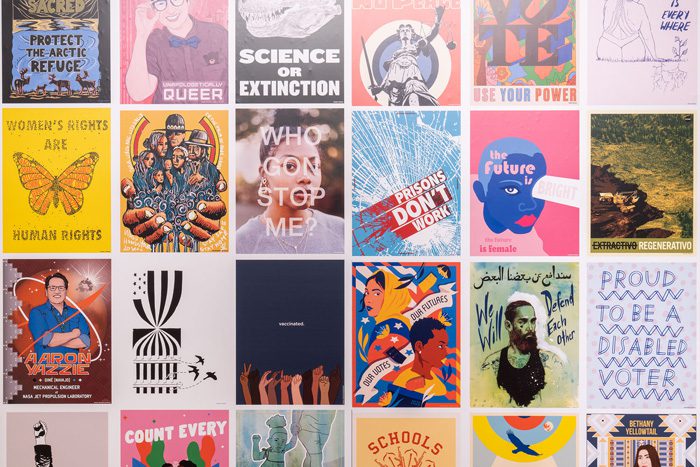

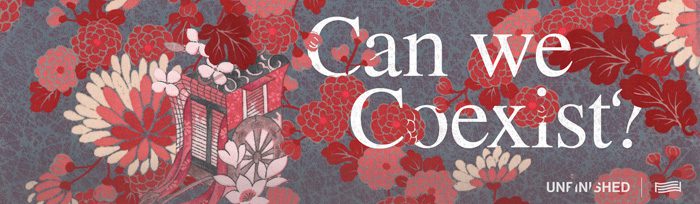

So far, For Freedoms, which is centered on healthy discourse and robust direct action, has held artist-led town halls and forums focused on civic dialogue. In June 2018 ahead of the mid-term elections, the group commissioned artist-made billboards that appeared in all fifty states as well as Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico. Each piece allowed the artist to ask a pressing and urgent question on a medium that’s normally reserved for commerce and partisan politics. Time magazine named the 50 State Initiative, which included artists and groups such as Ai Weiwei, Judd Foundation, and Guerrilla Girls, as “the largest creative collaboration in United States history.”

“When we think of civic action, you think of voting, filling out the census, canvassing,” explains Woo. “But as artists, we feel that civic participation can look like a lot of things—asking complicated, challenging questions or having difficult conversations at home or extending compassion to someone you feel is against you. It could look like saying the thing that no one else is willing to say.

“Art is not necessarily about answering questions. It’s more about getting you to think and to be more critical of your relationship to the world and the positions that you hold, especially these days when things feel ideologically driven,” she says. “People are very, ‘This is my stance, this is my position.’ I think that’s why art is so important because it doesn’t adhere to any mold. It’s naturally multi-dimensional and invites a multitude of perspectives and ultimately has longevity.”

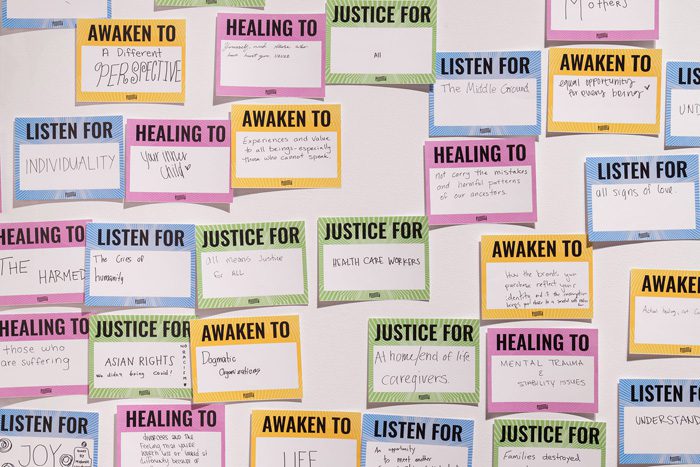

In February 2020, artists, academics, thinkers, and culturalists from all fifty states and beyond gathered in Los Angeles for the For Freedoms Congress. One result of the gathering, which prioritized social change discussions, was the Infinite Playbook, an open-source guidebook based on the principles of listening, healing, awakening, and justice. The document acts as an alternative, updated-for-the-year-2020 take on Franklin D. Roosevelt’s four fundamental freedoms: of speech and worship, from want and fear.

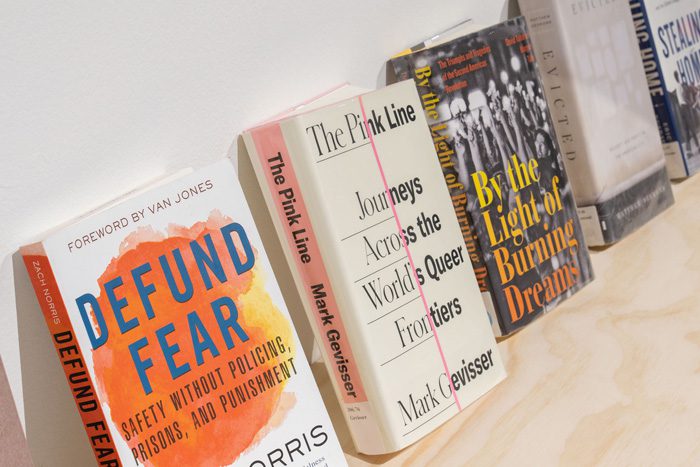

The Infinite Playbook opens the UMOCA exhibition Our Wake Up Call For Freedoms, which is scheduled to be on view through June 4, 2022. Additionally, the show documents some of For Freedoms’s other projects and calls for action, ranging from a voter registration station to a “creative library” for all age groups and book titles focus on discussing and illustrating core civil liberties. The exhibition also gives space for Wide Awakes, an art- and youth-centric anti-slavery movement from 1860 that For Freedoms reintroduced and commemorated in 2020.

“I think the exhibition’s strength is the sense of community that it fosters through the inclusion of diverse voices, including those in Salt Lake City, especially when it feels like there is currently a strong effort to push people further apart,” says UMOCA curator Jared Steffensen. “Visitors can see themselves and their beliefs in the work and feel connected to a broader community of people working hard for justice and equity.”

At one of its many cores, For Freedoms employs art in an attempt to universalize American ideals, such as freedom and patriotism, that Woo says have been co-opted by specific rhetoric.

“We all have something to contribute,” Woo says. “We all have something at stake here.”