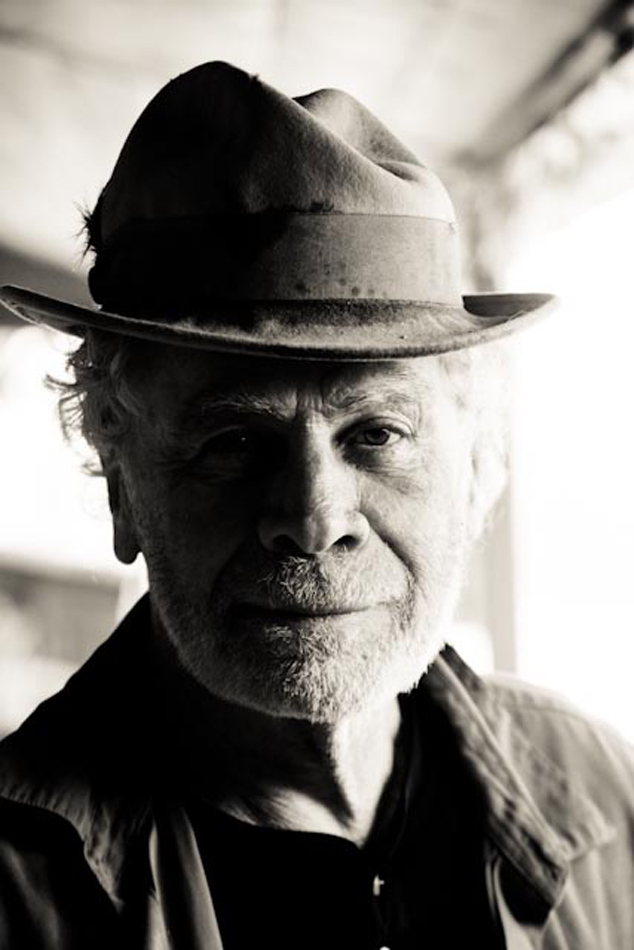

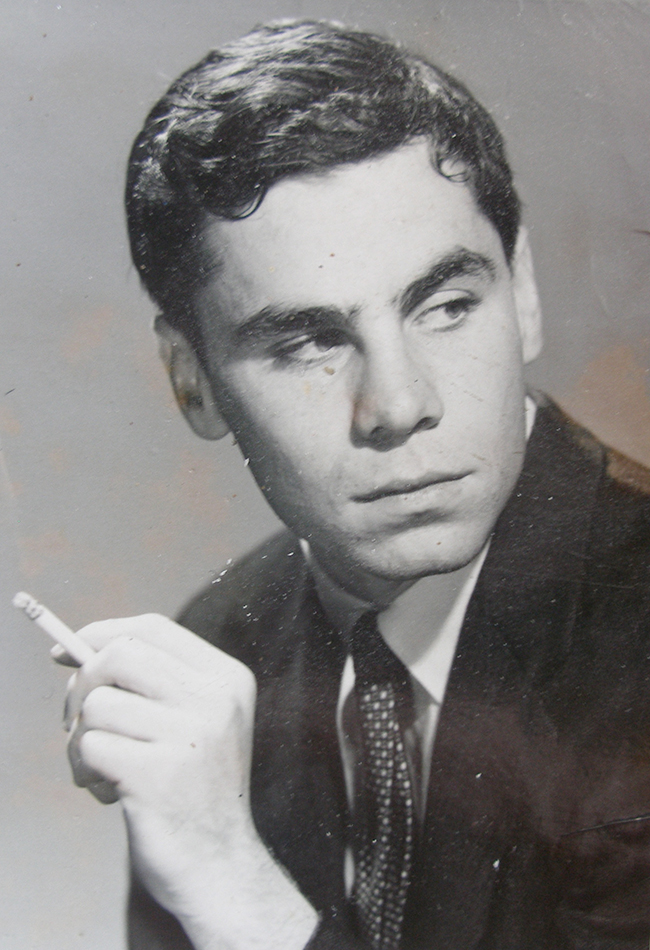

Guy Cross, who cofounded SWC precursor The Magazine, stoked Santa Fe’s turn-of-the-21st-century push to join a globalized contemporary art conversation.

Just before he first arrived in Santa Fe in 1978, Guy Cross parked in the middle of the road and set up his tripod.

“He takes a picture of his car ‘driving’ into Santa Fe: first instance of arrival,” says his goddaughter Bon Malten, recounting a story Cross told her. “Who gets out of their car to take a picture of this dusty-ass dirt road in 1970-something? It was like, ‘I’m here, I showed up, I’ve got documentary evidence.’”

In this theatrical and ad hoc mode, Cross trained his lens on Santa Fe for the better part of four decades, cofounding two arts magazines that reflected—and shaped—an image of the ancient cultural center as a contemporary art boomtown. His second Santa Fe-focused title, The Magazine, was a direct precursor to Southwest Contemporary.

Cross died in Santa Fe on November 13 at eighty-four years old, prompting a collective look at the legacy of a local publishing force whose creative and destructive impulses seemed hopelessly—and alluringly—entwined.

Santa Fe had become a hub for luxury goods: contemporary art, and also cocaine. Cross participated in both phenomena.

Cross was born in New York City in 1939. Before his move to the Southwest, he built a successful career as a fashion photographer in New York and London from 1967 to ’78. He was friends with actor Dan Richter, who played the prehistoric hominid that casts the bone into the air in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Richter knew John Lennon and Yoko Ono, two of Cross’s many famous portrait subjects.

“Guy came through the ’60s and ’70s with his friends,” says Judith Cross, Guy’s longtime wife. “These guys came out of that drug culture—heavy, but they created a lot of stuff. I remember one of Guy’s friends said that he wasn’t from this planet. He was wild.”

Cross’s mother and sister, Doris and Norma Cross, moved in other creative circles. Doris was an avant-garde artist who studied under Hans Hoffman and Robert Motherwell, and befriended Louise Nevelson; Norma hung out in Bob Dylan’s milieu for a time. The two women moved to Santa Fe before Cross, in the late 1960s, falling in with Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin.

By the time Cross landed in Santa Fe, it was on the cusp of a tectonic generational shift. The town of about 66,000 was becoming a hub for luxury goods: contemporary art from U.S. coastal cities and around the world, and also cocaine that flowed out of Colombia and along a U.S.-Mexico borderlands corridor. Cross participated in both phenomena.

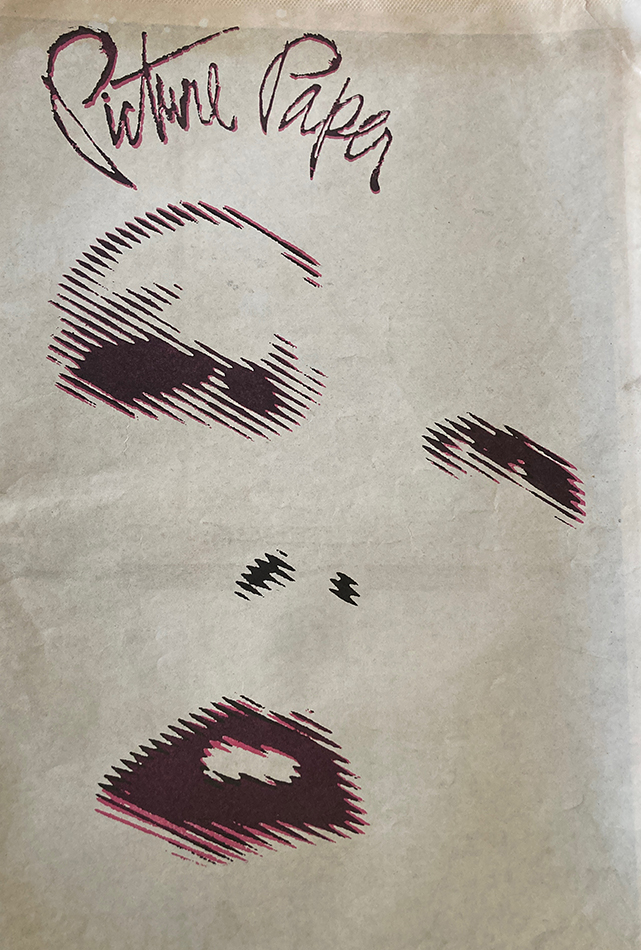

The year of his arrival, he cofounded The Picture Paper, which ran from 1978 to ’81. “It was like a tabloid. It was all pictures with an advertising section in the middle,” says Michael Motley, who was the designer for both of Cross’s Santa Fe publications. “It gives you a window into the nascent Santa Fe art world of the late ’70s and early ’80s. I met everybody through The Picture Paper.”

Motley reminisces about the early scene at Center for Contemporary Arts, which sprung up a year after Cross’s arrival (and underwent significant downsizing last year). In that era, CCA exhibited works by Jenny Holzer, Andy Goldsworthy, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Kiki Smith and Richard Long passed through, and Motley once spotted Richard Tuttle chasing after his five-year-old daughter Martha. Cecilia Vicuña, who recently received a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, mounted a solo exhibition.

He was a totally irreverent guy—not just to others, but to himself. I think he had a certain death wish.

Santa Fe’s broader contemporary art scene was also churning. “Fritz Scholder, R.C. Gorman, and Allan Houser were kind of the big names at that time, and Bob Haozous was just starting,” Motley says. “Then things got really interesting because you had [gallerist] Megan Hill [exhibiting] Larry Bell, John Fincher, Carl Johansen.”

Marina Abramović staged a performance (“naked, with a snake around her neck,” notes Motley) for Laura Carpenter, another powerhouse gallerist of the era who also showcased Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Juan Muñoz, and Susan Rothenberg.

“Guy covered it all,” Motley says. “He could whip up content in ten minutes. He did what he called a ‘beautiful interview’ with Magdalena Abakanowicz, and she said, ‘Ask me something interesting. These are really stupid questions.’ He was fearless.”

Likewise, Cross was far from precious about his imagery. Motley quotes Cross’s close friend and fellow photographer Elliott MacDowell, “He has the best line I’ve ever heard about Guy: ‘He taught me that it was okay to be out-of-focus and grainy.’ That is good advice in photography and life.”

There was a darker—and perhaps even obliterative—edge to Cross’s attitude, however. His friend of thirty years Willem Malten speaks of Cross’s lack of self-regard, which extended to his work. “He was a totally irreverent guy—not just to others, but to himself. He always diminished himself,” he says. “I think he had a certain death wish.”

Cross was a serial entrepreneur, running a one-man taxi service and a short-lived all-night restaurant. His black taxi was a front for another business endeavor: dealing drugs. An undercover cop tried and failed to buy LSD from him on a ride. He was eventually arrested and charged for cocaine dealing in the mid-1980s.

“He was always in trouble,” says Cross’s sister Norma of his early years. “One thing I can say about my brother that probably a lot of people don’t think of is that in certain ways, he was extremely brave. He met his challenges and didn’t crumble.”

He really did believe in there being an open discourse in the community, and fuck them if they didn’t like it. But he rarely had to say that.

Cross’s five-year sentence was eventually cut in half, and he even managed to attend his niece Zia Cross’s high school senior dinner during his prison time. Zia says, “He wasn’t the most emotionally tuned-in person until the last year of his life… but Guy, out of all of my uncles, he was there. He was my cool, kind of crazy uncle.”

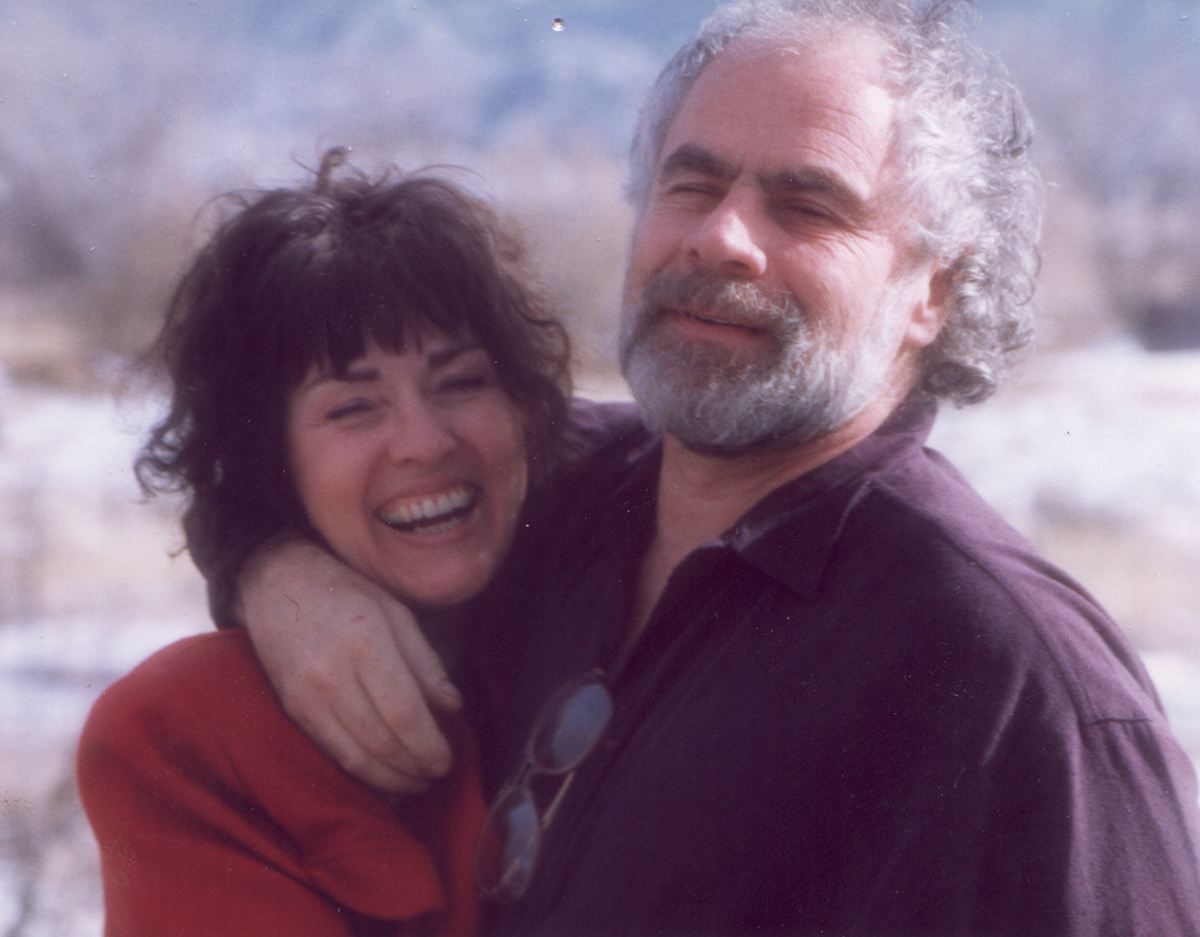

Having spent his prison time reflecting on his life in a semi-autobiographical novel, Cross set about turning things around. Judith reminisces about meeting Cross at a late-1980s Fourth of July party in Santa Fe and moving to Eureka, California, not long after. They founded a “little rag” there called Edge City Magazine, which ran from 1988 to ’92, and Cross switched from hard drugs to marijuana. Then Cross’s mother, Doris, suffered a severe stroke during a visit to Paris, compelling the couple to return to Santa Fe for good.

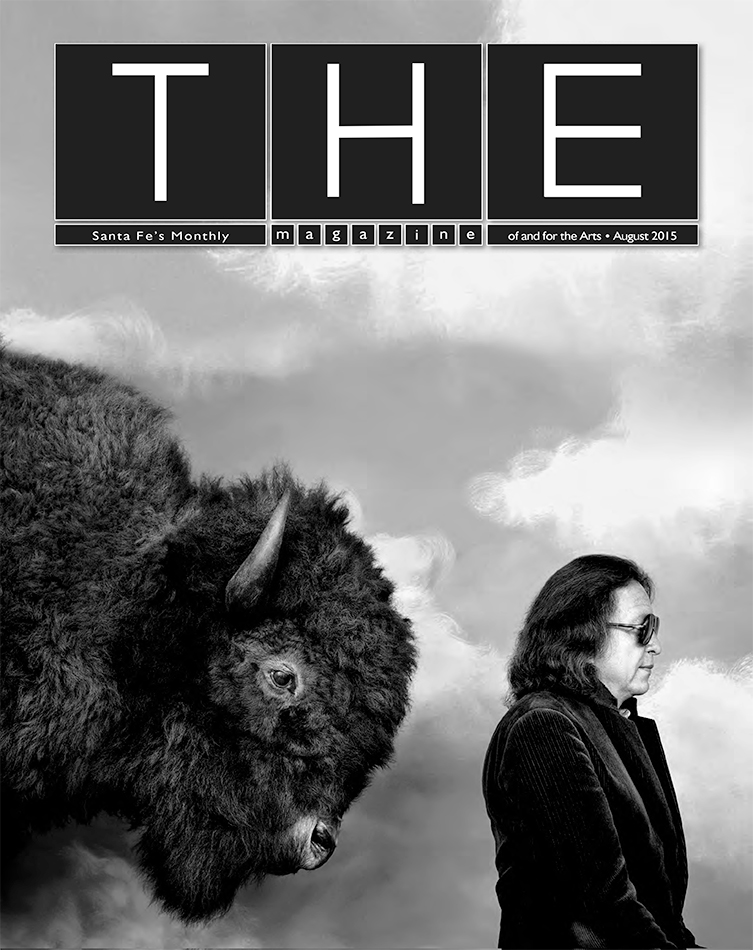

Judith points out that they had also run short on funds in Eureka. Starting another publication immediately upon arrival was their solution, and The Magazine was its generic-but-authoritative title. Like The Picture Paper, it landed just ahead of a turning point for contemporary art in Santa Fe.

SITE Santa Fe launched its inaugural biennial (now called the SITE Santa Fe International) in 1995, featuring Abramović, Holzer, Félix González-Torres, Anish Kapoor, Bruce Nauman, Meridel Rubinstein, and other boldface names. Patti Smith played during the opening festivities. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum debuted in 1997, mostly exhibiting historic works by the legendary modernist but drawing fresh attention from the contemporary art community.

Judith says, “[With The Magazine], we were trying to offer a critical voice about the art in Santa Fe, and New Mexico in general, because there was nobody doing that, really. It took off like blazes. It was just a thing that was ready, the market was open.”

Unlike The Picture Paper, The Magazine included words along with the pictures, but Cross was a predictably laissez-faire editor. “He allowed us to come at our reviews however we needed and wanted to,” says longtime The Magazine contributor Kathryn Davis. “He really did believe in there being an open discourse in the community, and fuck them if they didn’t like it. But he rarely had to say that, because he just so bon vivant, so debonair—you couldn’t argue with that, he was just so who he was.”

He idealized some of the greats, like Dean Martin and Elvis Presley. He wanted everybody to know him as that slick guy with the cool jacket and great hat.

Guy and Judith Cross ran The Magazine for twenty-four years, from 1992 to 2016. They sold the publication to Lauren Tresp, who eventually moved away from The Magazine’s hyperlocal focus and launched Southwest Contemporary for a regional audience. Cross’s goddaughter Bon Malten, who was born in Santa Fe in the mid-1990s and is now an artist in Portland, Oregon, never knew her hometown before The Magazine’s existence. She wonders if recent waves of transplants understand his influence—or even know of him at all.

“I think Santa Fe is definitely experiencing a changing of the guard, especially in the last five years,” says Malten. “The town created this reputation between the ’70s and the ’90s, and that carried over into the 2000s. Guy represented that old guard, who thought of Santa Fe as the Wild West, this edge of the map, and this place where artists leave New York and become enlightened by the desert.”

Malten says she’s struggled with aspects of Cross’s legacy over the years. “He idealized some of the greats, like Dean Martin and Elvis Presley. He wanted everybody to know him as that slick guy with the cool jacket and great hat. He did sleazy photography and kind of had this bad mentality. But he was beyond that by the time I came along. He always had some wild tale that we couldn’t really believe. Like, really, that happened?”

Cross is survived by his ex-wife, Judith Cross; his sister, Norma Cross; his brother, Ivan Cross; his son, Jason Cross, and Jason’s wife, Luna Rukmini Devi; his nephew, James Rodewald, and James’s wife, Marella Consolini; his niece, Zia Cross; his grandchildren, Taj and Camille Cross; and his ex-wife, Elizabeth Munro, who is also the mother of Jason. The family is planning a memorial service, which will take place in Santa Fe early next year.

Correction 12/10/2024: This article previously referred to Judith Cross as Guy Cross’s widow. Court records show that they were legally divorced in December 2024.