Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery debuts at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe in summer 2022.

Any pottery piece that was made long ago speaks to me, and I feel a strong connection to these vessels. The creation of clay, the mixtures, the coiling and shaping, the tools used, and finally the process of firing the completed piece—all are awe-inspiring. I feel empowered by our ancestors, because they knew how these pieces should be made and completed. Our ancestors were ingenious, and our people remain so today.

—Shirley Pino (Santa Ana Pueblo)*

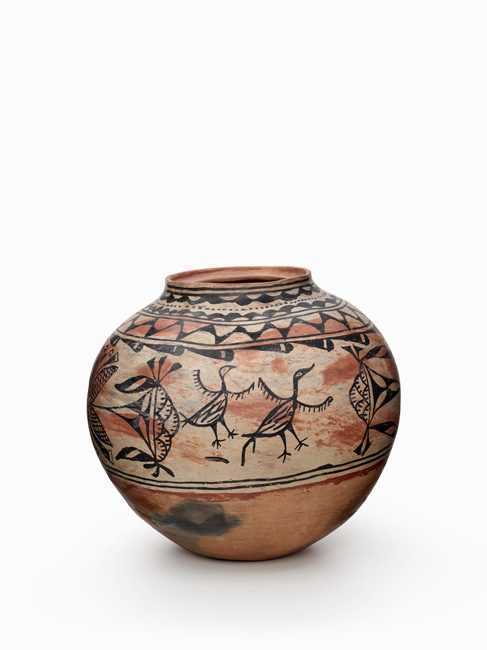

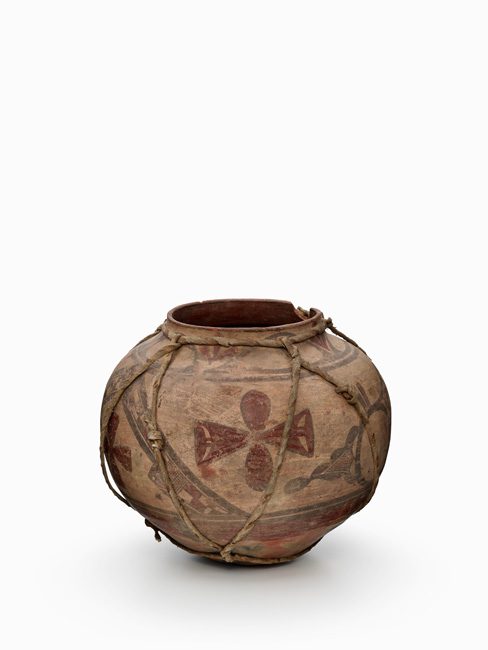

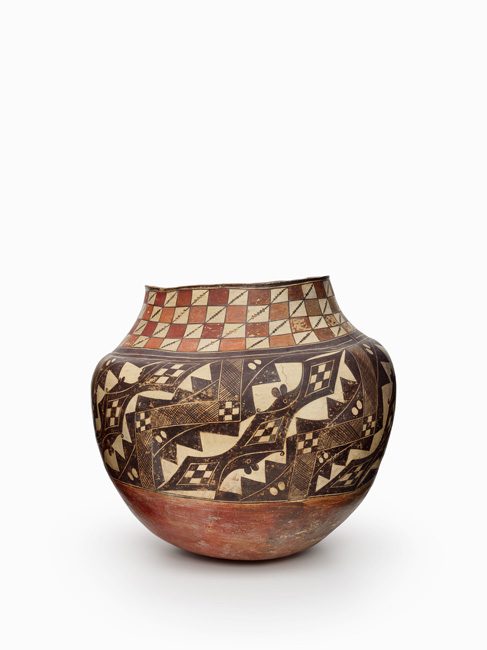

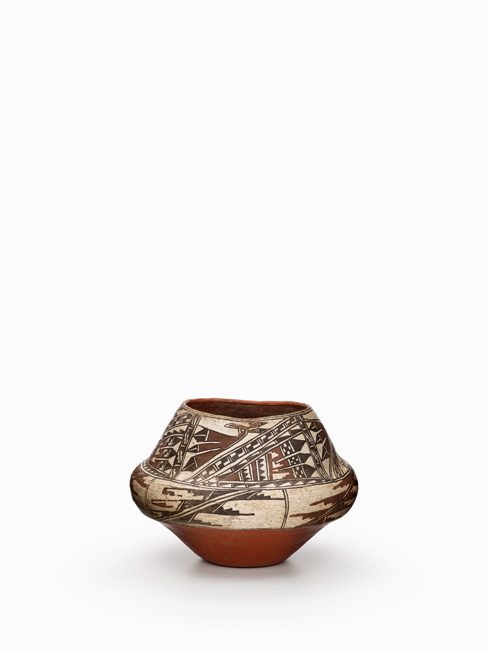

Pottery is an art form that has sustained Pueblo peoples since our emergence onto this world. Pottery has deeper meanings in our culture than decorative jars sold on the market. As in the past, it has served utilitarian, aesthetic, and spiritual purposes. Pueblo potters pass their knowledge and techniques from generation to generation. Over time, pottery making has evolved with differing techniques, shapes, tempers, and designs. Many talented potters today use traditional methods to create pottery, while others push the limits with innovative and stylish designs, and still others blend traditional and contemporary methods.

Collectors value all types of our pottery. Pueblo pottery is unique, with each community having its own methods to create ceramics with differing types of clay, color schemes, paints, designs, shapes, and firing techniques. The ability of potters to shape their creations without a wheel is a remarkable feat. Our ancestors who made pottery had a keen sense of artistic style and often made pots with near perfect symmetry. Pottery crafting in the Pueblo households truly links the past with the present and future.

Surviving an all too often dark and ugly past resulting from Spanish and United States’ attempts to destroy Pueblo culture, pottery making continues to sustain Pueblo cultures and their economic livelihood. Museums too have a dark past of unethical collection practices and imposing an authoritative voice over other people’s cultures, where little to no community consultation occurred. Thus, it is no surprise why many Indigenous peoples have preconceived notions and negative views of museums. There is much work still to be done and much more consultation which needs to happen. However, times are shifting towards more inclusive voices in museum spaces.

Now, a historic event is in the making. The year 2022 marks the 100-year anniversary of the founding of the Indian Arts Research Center collection at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Pueblo pottery will be central to this centennial celebration. The Vilcek Foundation has partnered with SAR to showcase their first major exhibition titled Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery. It will open on July 31 at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe, and will feature more than 100 historic and contemporary works of Pueblo pottery.

Remarkably, the Pueblo Pottery Collective, a group of more than sixty individuals from twenty-one tribal communities, is curating Grounded in Clay in collaboration with the collections of SAR in Santa Fe and the Vilcek Foundation in New York, with objects from the nineteen New Mexico Pueblos, Ysleta del Sur Pueblo of Texas, and the Hopi Tribe of Arizona. This development reflects the growing empowerment of Pueblo potters to take charge of the processes involving the defining, shaping, contextualizing, and displaying of their craft.

SAR’s Guidelines for Community Collaboration, first published in 2017, is a helpful web-based resource that provides insightful information about how and why museums and Indigenous communities should work collaboratively on projects. Grounded in Clay applies this collaboration model to the project, with the museums overseeing this project enabling the potters to write their own narrative about their works selected for display. This kind of largescale collaboration is rare and unique in that the exhibition was not curated by a small museum curatorial team but rather by individuals from Pueblo communities whose pottery is represented in the exhibition.

Often, Pueblo pottery has been referenced from an ethnocentric, Western point of view or from a fine-arts perspective. For this exhibition, however, Pueblo people themselves stand distinctly as authoritative voices with the ability to share, define, and conceptualize the works represented from a personal connection. This achievement must have something to do with the decolonizing winds of change.

Elysia Poon, the director of IARC, noted the significance of having Grounded in Clay open at MIAC, on Pueblo lands, the lands that gave birth and a cultural essence to the vessels to be displayed. In addition, she mentioned the members in the collective are representing their personal connections to clay, rather than representing their whole community.

The Pueblo Pottery Collective is made up of artists, writers, professors, and community leaders. Some of the co-curators include such noted artists as Kathleen Wall (Walatowa/Jemez), Diego Romero (Cochiti Pueblo), Michelle Lowden (Acoma Pueblo), and Rose Simpson (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo). The group is as diverse as it is creative. Its members expressed their personal perspectives as they planned and reached a consensus about the exhibition. In other words, they decided collaboratively on the themes and narratives that will be seen.

Grounded in Clay will feature around 100 vessels, all of which have their own intimate story, stories told by the Pueblo Pottery Collective co-curators. The exhibition will explore themes of utility, elements, connections through time and space, and ancestors.

“Traditional” curation models for Indigenous art have often come from a singular perspective, with one voice interpreting the art, often from non-Indigenous curators. This is why Grounded in Clay is so remarkable because of its empowering effect that privileges and highlights personal narratives from Pueblo people themselves. Each member of the collective selected up to two works and wrote their personal narrative about the pottery for viewers to read. The museums involved merely served as facilitators during the communal planning, discussion, and selection process.

Brian Vallo (Haak’u/Acoma Pueblo), Pueblo Pottery Collective member and former director of the IARC at SAR, played a major role in the development of this project. Vallo noted that during his term as director of the Indian Arts Research Center, he established a relationship with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and later with the Vilcek Foundation. Discussions with the Met led to the idea of featuring the IARC Pueblo pottery collection in the American Wing at the Met.

Tony Chavarria (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo), a member of the Pueblo Pottery Collective and curator of ethnology at MIAC, also provided his insights and experiences working on this project. When asked about the collaboration for this project and the inclusion of so many diverse Pueblo voices, he responded, “This is one of the most collaborative projects I’ve ever been involved with; this project has been this intense community collaboration. The people involved were able to be involved as much as they wanted to, from start to finish. The participants were very engaged. The Collective members brought their life’s knowledge and are sharing it with people. The Collective members were able to select the works they wanted to write about. Many selected vessels were not perfect, or were broken, because it is a part of the story.”

I then asked Chavarria what his favorite part of the project was, and he replied, “It was listening to the other artists when they shared their write-ups. The Collective members wrote from their own perspective, from their own experience, so there were a wide range of voices. The write-ups were very personal and relatable.”

Museum and community collaborations are important as they show institutions are taking steps away from a long history of unethical collection practices and assuming the authoritative voice of other people’s culture. This large-scale community collaboration could serve as a model for other museums to adopt. This is important as it shows Indigenous museums and Indigenous communities the extent of what collaboration could look like. Consultation with Indigenous communities is starting to become more widely practiced by museums. Tribal consultation and inclusion of Indigenous voices allows Indigenous communities to ensure culturally accurate and appropriate information is being dispersed in a manner they approve.

There is so much work involved in pottery making; although it is a labor-intensive job, potters continue to carry on the tradition in order to preserve Pueblo culture in our communities. For many Pueblo people, we have grown up around family members who make pottery or been around pottery our whole lives. This is what is so beautiful about this exhibition because so many of the Collective members can relate on a personal level to the works represented which will be seen in their write-ups. It is rare to hear so many Indigenous contributors in a museum space share their personal connections and knowledge. This is a wonderful opportunity to learn and see the diverse artistic styles which differ from Pueblo to Pueblo ranging from historic to contemporary works. Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery is truly an exhibition you will not want to miss.

*Elysia Poon, Rick Kinsel, and Pueblo Pottery Collective, Grounded in Clay: The Spirit of Pueblo Pottery, Merrell Publishers Ltd, 2022, p. 194.