The depletion of Utah’s Great Salt Lake is a symbol of the state’s worsening water crisis and has, throughout the past few years, inspired a diverse array of artistic responses.

For the estimated forty million inhabitants who rely on the Colorado River, the West’s worsening drought is an existential threat. Elected officials thus far have only managed lip service, not the action necessary to avoid the catastrophic outcomes sure to follow from rampant mismanagement and the establishment of massive population centers in a barren desert climate.

During the pandemic, an iconic artwork became a symbol for the plight of the Great Salt Lake (GSL). Once completely submerged in water, the lakebed surrounding Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) has now receded from the famous earthwork, a harrowing reminder of how drastically climate change has impacted the region.

The GSL is deteriorating rapidly, exacerbated by population increase, climate change, and decades-long drought. Residents along the Wasatch Front face what has been called an “environmental nuclear bomb” in the years ahead. In a critical respect, the GSL is a visible symbol of and conduit to our understanding of the region’s broader water crisis.

And while the fame of Smithson’s earthwork brings the issue to the fore on a national level, other artists more local to the area have also used their craft to highlight these critical issues. In surveying the artistic responses to Utah’s water crisis, fascinating themes emerge—namely how worsening drought conditions and the demise of the GSL illuminate the dangers of climate change while exposing the systemic forces underlying power and access in the region that have been in place since the time of white pioneer settlement.

ARTISTIC RESPONSES TO THE DYING GREAT SALT LAKE

In June 2022, the Salt Lake Tribune reported on Spiral Jetty’s receding water levels, noting that the earthwork has become a “symbol of the lake’s health.” A stark image of the famous work coiled around a gray, cracked lakebed accompanied the article, a premonition of the years of difficulty to come.

The warning was, of course, not new for residents. Yet the visual of Smithson’s iconic earthwork—a boon to the state’s art credibility—resonated at a time ripe for a local and national awakening.

Invariably, when geological disturbances or oil and gas interests have posed threats to the Jetty over the years, a public outcry ensues with calls for the preservation of Utah’s “state artwork.” And while no one wishes to see the Jetty obliterated, such uproar for preservation seemingly ignores the extent to which alteration—both gradual and extreme—has been an integral part of the Jetty from its very inception. In Smithson’s short but impactful 1968 essay Sedimentation of the Mind, the artist argues for entropy as an inevitability and a conceptual process in his artmaking.

And while the Jetty’s current state serves as a more recent symbol of the state’s worsening water crisis, Utah artists have explored this issue for years in highly creative ways.

Last year, poet Nan Seymour crafted a collaborative poem and site vigil, Irreplaceable, during the two weeks of Utah’s 2022 legislative session. What began as a small poem published on her website flourished into a community project with written contributions from several individuals who visited Seymour at the lake. Her project will result in a publication and has moved state lawmakers to speak frankly about the dangers underlying the lake’s demise.

Elsewhere, visual artists have focused on the unique geological processes underpinning the vast and sacred lake. Chauncey Secrist’s Migration Point (2019) is a beautiful photographic series capturing bird remains enshrined in salt and grime. Death and entropy are, it seems, constant forces underlying desert ecology, irrespective of the harms imposed by human intervention. Cassidy Eames’s collaborative dance and performance piece Salt and Ashes (2022) pays homage to the ancestral homelands of the Ute, Paiute, Goshute, and Shoshone peoples who came before white pioneers, while making a plea for collective action to save the Great Salt Lake.

WATER AS AGENT OF PRIVILEGE AND ACCESS

While the Mormon pioneers are lauded in the history books for transforming an inhospitable, previously inhabited landscape in the mid-19th century, the very first white faces to encounter Utah were members of the Dominguez-Escalante expedition of 1776. Due to its high aridity, these ambitious explorers recommended against acquiring the region as a Spanish settlement, recognizing and foreshadowing the ecological issues that were all but predestined to occur.

Indeed, the West faces a host of interrelated crises—overconsumption, rising temperatures, receding lakebeds caked with toxic chemicals, increasingly prevalent wildfires—that may eventually render this region, once considered a prize of Manifest Destiny’s rugged individualism, inhospitable to life.

While such environmental calamities are becoming impossible to ignore, this late awakening to the existential crisis of the West ignores the ways in which tragedy and exploitation have pervaded this region for centuries, evidenced by atomic testing, Indigenous displacement and genocide, and the imprisonment of Japanese Americans during the Second World War.

In this respect, water is emblematic of this inequity, its exploitation revealing historical issues of access and privilege. By investigating these systemic forces underlying water consumption, several artists have complicated the inclination toward mere conservation activism that dominates much of the political discourse.

Artist Cara Despain devises large-scale paintings composed of wildfire ash to call attention to the decimation caused by worsening drought and hotter temperatures in the West. Her work also contends with the haunting history of the “downwinders” of Southern Utah, a generation of residents whose lives were permanently altered by the radioactive fallout of atomic testing in the Nevada desert.

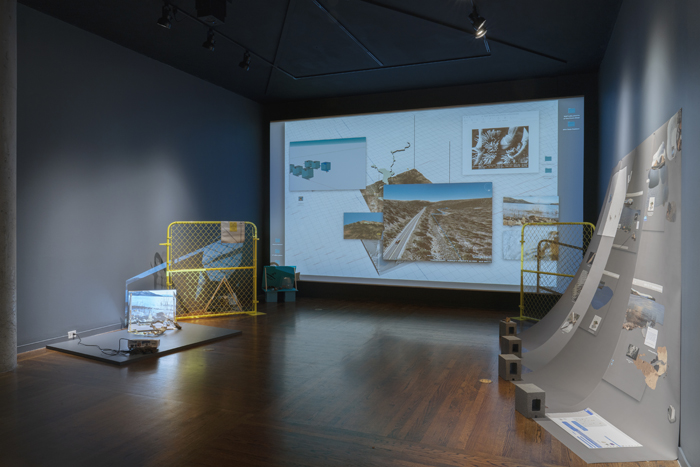

Tiana Birrell’s multimedia investigations delve into the overconsumption of valuable resources—namely water—that fuel the data centers in the Salt Lake Valley, the state’s main population hub. Her 2021-22 exhibition as an artist in residence at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art combined installation, photography, video, and performance to highlight the often-exhaustive resources underlying the sleek veneer of the internet and accompanying digital spaces. She sees her work as underscoring the “data centers and the copious amount of water that is used to cool the servers as a way to bring a materiality to the interconnected networks of signals and communication called the internet,” according to her website.

Combining text graphics over original footage and internet clips, Zachary Norman’s six-channel video work This Storm is What We Call Progress (2020) highlights the erasure of natural habitat resulting from Utah’s highly controversial Inland Port. A project in Salt Lake City’s under-industrialized northwest quadrant that would span several thousand acres, it has generated criticism since its inception. The project’s environmental impact could lead to further depletion of the region’s already tenuous water reserves while adding to air pollution in the Salt Lake Valley.

At various junctures, these artists undermine the fallacy of the idyllic Western landscape, pristine and uninhabited, that fomented settlement colonialism and sustained exploitation. Instead, their work calls attention to the continued toll exerted on the land that renders the region even less hospitable to human life than it was centuries ago.

As Utah experiences a population influx—Salt Lake City ranked in the top ten fastest-growing cities in the U.S. in 2022—the environmental realities faced by inhabitants of the Western states, already impossible to ignore, will be greatly exacerbated. In work that illuminates the beauty and the plight of the Great Salt Lake, the overconsumption of valuable resources, or the damaging histories we’re all too quick to ignore, artists give voice to the existential crisis unfolding before us.