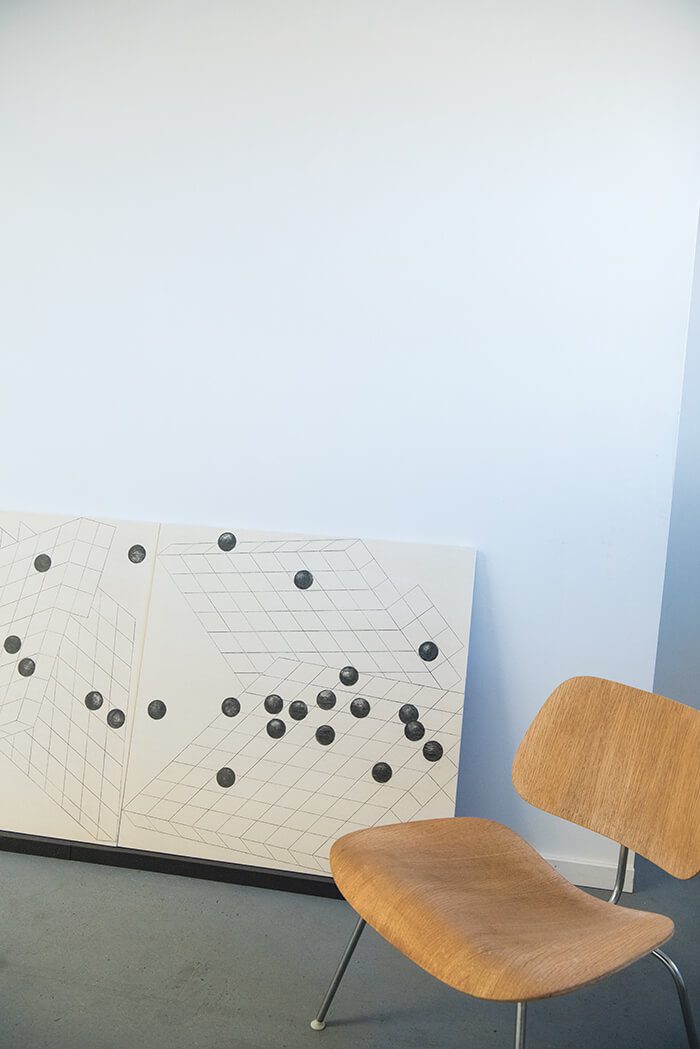

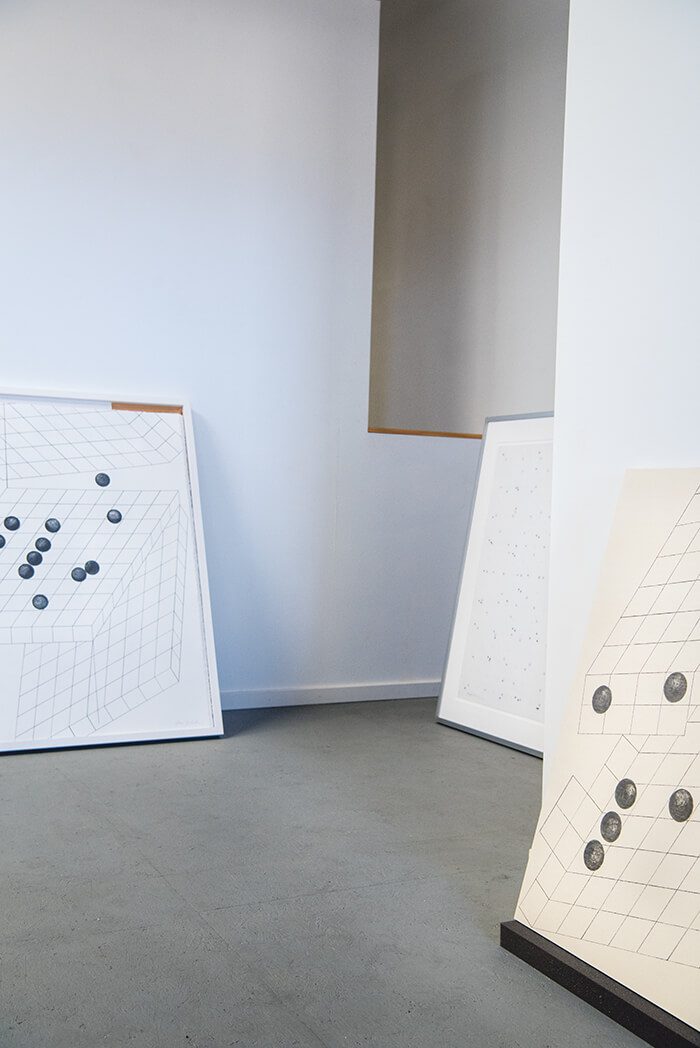

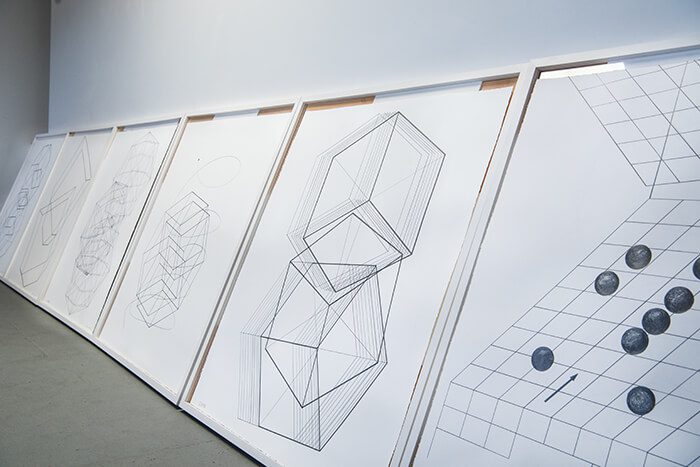

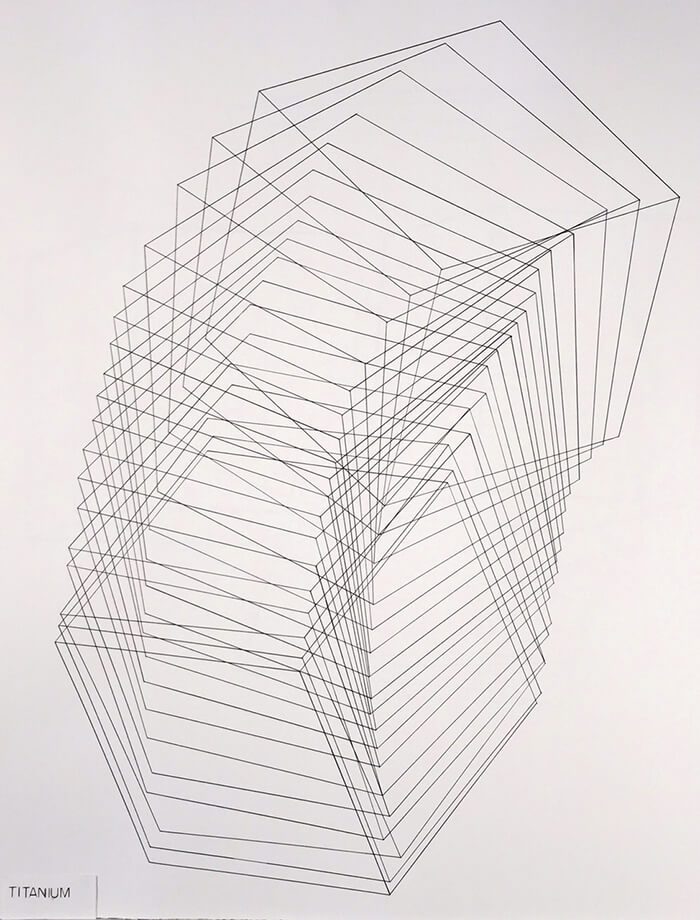

Spending a morning with Gloria Graham in her drawing studio is like being in the world’s most inspiring chemistry class. She speaks with sheer awe about the structures and movements of molecular particles, telling personal anecdotes about carbon and silicon, acting out the effects of selenium. While her drawings are abstract distillations of the substances that make up the universe and the human body, her own mind and body dwell in the natural world. Growing up on the coast of Texas, she recalls the way hurricanes—hurrakins, in her warm drawl—shaped her understanding of her place in the universe and shook up her perspective. With a botanist for a grandfather, Graham was surrounded as a child by exotic trees and plants, and she had access to a big desk and plenty of sheets of architectural paper. Her current drawings, on 36 x 36 inch sheets of paper, lean against the wall of her studio in Plexiglas frames that also serve as portfolios. Titled and signed, they appear at a distance to be finished works, but Graham informed me that they’re all still in progress. She can always add a line here or there.

Like drawing itself, Graham courts the specificity of a moment—a shadow cast at a particular time of day, a library catalogue card as it catches fire, the shape of a molecule as it moves. She savors the feeling of moving a 2B pencil across paper. Even in large-scale drawings, Graham’s line captures movement with utter precision, concretizing through abstraction, rendering the ephemeral tangible. As with the paper and the desk that made her an artist in childhood, Graham knows that structures and materials, at once fixed and dynamic—finite but unbounded—make us who we are.

Jenn Shapland: Why did you get interested in molecules and molecular structure?

Gloria Graham: The body is made up of so many different things, and we’re very familiar with those. But I was reading about supernovas, about that time, the explosion or implosion. And the things that come out of those are the very same things that we have inside of us. For instance, this is Salt. You can feel: it even looks like salt, a particle of salt. And we certainly have salt in our bodies. But at the same time, what happened in my mind, I thought, “Well the particles are not just still when they come out; they’re jumbled up.” So I kept working on them, crazy like. I enjoy the idea that they absolutely move around.

How do you study the structures? Do you read about them, do you look at pictures?

Images, sometimes at the science library down at UNM. I’ll find a little tiny one, and then I’ll just start drawing from off of that. This is an older piece. I did quite a few of these.

Three layers of paper. That’s architectural paper that you can see way in the background. In my large studio out of town, I would work on the floor, because the floor was so wide and so big. I started shifting these papers around, and I really like the craziness of it. I think that is part of what the artist can do with just very still objects.

Yes, just keep moving them around. What made you want to enlarge these structures?

I’m not really sure. An impulse. You get tired of working on something small. This is Silicon. If you drew a straight line to each of the dots, you’d come up with one of those figures, the structure of silicon.

I’m interested in the relationship between drawing and photography in your work, because they’re often in conversation. For example, in your Earth Moves Shadows series, shown last fall at 5. Gallery.

As a matter of fact I can show you where these came from. [Opens a flat file drawer full of what appear to be rocks.] I’ve had these probably since the 1970s. They really come from the plateau up in Taos. You just have to hold one to get the feel. These are archaic tools. [Hands one to me.]

I don’t even know how to hold it. I mean, I feel powerful.

They’re just so heavy. But it’s a beautiful, beautiful object.

And they are clearly designed to fit the hand.

Oh, definitely. I had these in my solar studio, which is all south-facing windows to the floor. They’d been sitting there for such a long time. I began to notice some shadows while I was drawing, working in my studio. It occurred to me that people of my era think of “sun up, sun down,” but don’t too much think of “the earth is moving.” You guys grew up with that, the idea that the earth is always moving and that’s what makes the shadows. It was just so dramatic in my mind. After I photographed the tools, I set them back exactly on top of the prints. Then, every hour, from seven in the morning to seven in the evening, I drew their shadows. It’s to represent that movement that happens in the earth, which is such a fantastic idea. When you think of these being up in Taos plateau between 6000 and 2000 BC, you realize the sun has been hitting that and making shadows that whole time.

Time is often a crucial element in your work. You’re emphasizing both the ephemeral and also the specificity of a particular moment, or a particular shadow. Is that something you’re thinking about?

Definitely. With my series Chance Photographs of Blue Light. Just by chance while I was taking photographs of this little lighted box—this is all outside again. I just love doing outside. I just put my hand across the shot, like that, and I went, “Wait a minute. Where’d that hand come from? And why was it blue?” I recognized that every afternoon at 3 o’clock, we in New Mexico have this blue shadow. If it is a very clear day, you’re gonna start seeing it in everything. There are some old western paintings you’ll see different places, and they’ll have this horse and the blue shadow. That’s what that’s about; somebody else realized it. It has to do with what is happening out in the atmosphere again.

Tell me about where you grew up.

I grew up in Texas, along the coast, where there were dramatic hurricanes like the one that occurred last year. Every summer was the same. I had this fantastic dad who was a botanist, horticulturist. That was the reason my family moved to that area: my grandparents were from upper New York state, and they chose that particular property because all the wonderful rivers that cross Texas bring this soil that’s very particular there. So they exported some very special plants to Kew Gardens in London and places like that. It was a very large tree nursery.

Because we had those enormous hurricanes every year, I really began to think, “What is out there in the universe?” They were just tremendous storms that would come in. I think a lot of people are like that along that coast, because it does change their lives. It’s right on the Louisiana border, Beaumont, Texas. It’s a wonderful place, all these cypress trees. The oil industry came in around that time, 1906 or 1910. Oil was discovered there. But my grandfather said, “Not on my property. It will ruin the soil.” And he preserved it.

JS: When did you first start drawing?

I always say that I became what I am because I was allowed to. I was allowed to draw when I was a very young child. And because of the tree business and the landscape business, they had a very large desk, and I sat at this desk when I was probably eight years old. And they had all this large paper, and I was allowed to just sit there and do things. I mean, not too many kids have that kind of paper! I did drawings and a lot of it was on that same scored [architectural] paper, because that’s what they had.

I had these two older sisters, and they came to study in New Mexico with a well-known Chicago artist, Frederic Mizen. I was only thirteen, but my sisters said, “Why don’t you come along with us?” This was up in the mountains behind Las Vegas. It’s quite beautiful there. We were drawing all summer long. And Meisen said, “Okay there’s the mountain edge. Just draw it over and over until you have the feeling of that very mountain.” It wasn’t like you just took a brush and went very quickly. You had to draw that same mountain almost every day. And every time you would draw it, you would get more of a strong feeling about it.

So New Mexico has been a part of your mental landscape for a long time. Now that you live here, do you feel your work is informed by the place or related to it in some way?

Definitely. I don’t call myself a naturalist, but I just love being in the natural land, outdoors, in the wilderness, more wilderness than I can possibly get with. For instance, at the other place we have out of town, a mountain lion walked across our deck. And then a teenage bear came and, like, sat against our glass window. I love to be in that situation. I like the vibrance out here. And the enormous amount of sun. There’s a spark it adds to your life. It’s one of the reasons I continue running. I’m not sure how many years I can do it. But I just love either walking or being out. It just makes me feel quite alive. I just have this sense with plants: I don’t know how that happens, but I’m extremely connected with them in some form. Small plants as well as big trees.

This piece is Selenium. Do you know locoweed? You haven’t been here long enough. It’s a plant that grows in all the fields. And farmers just hate it, because it makes—and I’ve watched this—it makes cows and horses roll their eyes, and they dance around and they just go crazy. They actually give selenium to certain people to kind of settle them down.

What’s your routine like? Do you have any routines, as an artist, around your practice?

My husband and I have a small apartment that’s in town a bit, and we promised never to sleep in the same place where we had a studio. For us, it kind of interferes. You come back after being refreshed, you come back to the studio, and you just feel intensely about what you’re doing. So, in other words, if we continued on intensely all night in our studio, we wouldn’t have that really fresh feeling in the morning. But we work, both of us, every day, coming down here to the studio, every day of the week. Saturday and Sunday doesn’t mean anything to us. We just want to get back to what we’re doing.

You mentioned reading a lot as a kid. Do you still read a lot? What are you reading lately?

Oh yes. I read everything. Like Paul Stamets’s book on mycology [Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World], about the growing of medicinal mushrooms. And things like that. Stephen Hawking, of course. I like “Look at the stars and not your feet.” His humor is so fantastic. And to be so ill, as he was, and you just can’t imagine that he could still be so humorous. But I think he gave us all a good perspective.

Well, I kind of think your work is doing something similar with giving us a different perspective.

I like to jiggle myself, I like to kind of shake myself up out of different things. I know I’ve always been rebellious, unfortunately. I’m not religious, which my mother was. I just am always thinking of different ways to be, to show, to help people.