Vince Kadlubek is running late. When I arrive at the repurposed bowling alley, I inform the desk clerk I have an interview appointment, and he promptly tells a colleague. She approaches me, a walkie-talkie hanging from her belt, looking authoritative and efficient. “And you are? And you are with? And you’re here to see?” She directs me to a sofa while she contacts Kadlubek, the CEO of Meow Wolf. The lights are bright, and the neon-patterned gray carpet reminds me at once of my childhood in the early nineties, of all the skating rink birthday parties, the laser-light backgrounds for school photos, the puff paint. Soon Tara informs me that Kadlubek is “appointment after appointment, boom boom boom,” and he’s going to be about forty-five minutes late. She offers to “wristband” me so I can tour the House of Eternal Return, Meow Wolf’s twenty-thousand-square-foot immersive installation. Admission into the House is seventeen dollars (twenty if you’re not a New Mexico resident), so I take the wristband.

The House of Eternal Return has a narrative, but it’s not a narrative that necessarily dictates how a visitor should move through the space. Anchoring the exhibit is a Victorian house, the home of the Seligs, a fictional family from Mendocino, California. There’s an old tube television in the living room, a checkered linoleum kitchen floor, and generations of family photographs lining the stairway. It’s all so flawlessly normal—if by that word we read a specific demographic that Americans have been trained to think of as normal: suburban, middle-class, white. I scan the rooms on the first floor. A young couple lounges on the stuffed sofa, flipping through magazines. People pass casually through the refrigerator or the fireplace into the more fantastical parts of the installation. Multiple other entryways open onto a sci-fi/fantasy network of passages, nooks, and rooms designed to disorient the audience spatially, to transport them into an alternate reality. I spend some time lounging in a lush, jungle-like environment made almost entirely from carpet scraps.(1)

I have recently seen mother!, a nearly irredeemable movie set in a large Victorian house. In the film’s climactic scene, throngs of people invade it, set up camp, and summarily destroy its interiors in a frenzy of religious zeal. Now, in the House of Eternal Return, I watch the tourists and children run their hands over the walls, rifle through papers on the desks, thumb through books, and bang the pipes and other surfaces, looking for clues to the narrative. The adults behave like children; the children seem rapt. The House itself is so meticulously constructed, each detail art-directed and set perfectly, that it’s difficult not to feel like you are one of dozens of strangers invading and ransacking someone’s home. The thrill it elicits is automatic.(2)

After visiting the adolescent Selig daughter’s hot-pink bedroom, which is covered in Tiger Beat–style posters and eerily empty, I walk downstairs and encounter a futuristic white room. In the center is a thick column where the holographic image of a woman hovers over a touchscreen. This is “Portals Bermuda,” an interdimensional travel agency that will transport you to your choice of four locations: St. Malibados, Todos 7, Murok-Inoo, or Viridian Heights. I choose Viridian Heights, and the hologram instructs me to move into a corridor. There, another robotic voice repeats, “You are okay,” and, because I’ve been kind of not okay since last November, I feel strangely comforted before laughing at my own sensitivity. I place my palm on another touchscreen, and the doors open onto the carpeted forest I had just encountered.

I continue through a series of rooms, elaborate installation after elaborate installation, until I happen upon an older man, probably in his seventies, sitting quietly and alone while his own private disco of flashing lights and electronic dance music swirls around him.

Above the mossy forest of Viridian Heights stands a series of treehouses, intricate little hideaways with pillows or benches that I imagine are a teenager’s dream, connected by platforms and walkways. Looking down from above, it feels possible to get the lay of the land, to begin to map the space and all its networks of rooms opening onto rooms. I see a wood-plank floor below that I haven’t noticed before, so I begin to make my way toward it. By the time I reach the first floor, I’ve lost all sense of direction. I never find the wood-plank floor.

Also on the upper floor is a dark room outfitted with a grated metal screen on the wall. Projected images of a group of people, presumably the Seligs, flash on the grate as voice-overs mix with ethereal sound effects. I stand behind a real-life family, father, mother, and kids, for several minutes as they remain in this room, unmoving, silent, entranced.

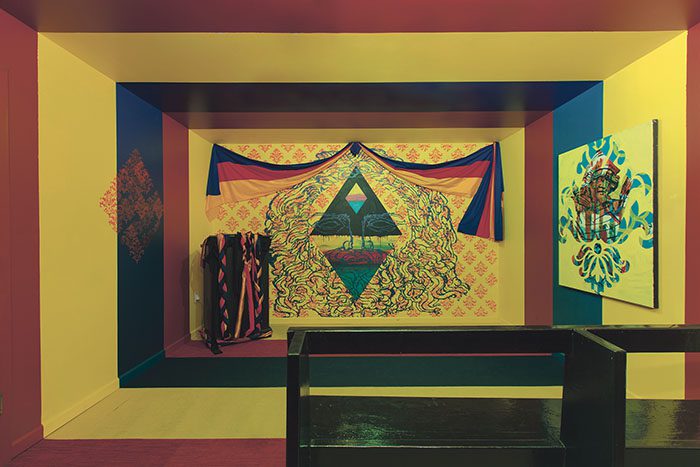

I happen upon a small chapel space with pews and somber music. Paintings adorn the walls, the largest facing the pews like an altarpiece. As the lights flood the space in alternating colors, the compositions of the paintings shift: a man’s (in this context, almost Christlike) face, abstract organic shapes. I’m not religious, but I am a sucker for visual stimuli, and exultation is not an uncommon effect of church or art. I stand up and make my way back to the lobby.(3)

• • •

“We made up our own jobs! We invented jobs for ourselves and all our friends.” Caity Kennedy, Meow Wolf’s Chief Creative Officer, and I are sitting outside the collective’s newest office and production space in south Santa Fe, a massive industrial hangar that once manufactured Caterpillar brand equipment. Its most startling feature is a gigantic interior crane installed on tracks along the hangar’s ceiling. This was the most obvious material clue I saw that day that Meow Wolf has big plans. A few employees tell me that a major expansion is in the works, but nothing has been finalized. Austin, Denver, and Washington, D.C., are some of the cities on their list.

“We made up our own jobs! We invented jobs for ourselves and all our friends.”

The sense of wonder and glee that tinges Kennedy’s statement about how she and her friends had somehow figured out how to make money doing what they love is not unique. All of the Meow Wolf employees I speak to for this article seem awestruck at their own luck. Art Director Nicholas Chiarella, who has been with the collective off-and-on since 2010, recognizes an irony and even humor in Meow Wolf’s ability to create a successful business out of art. He references a lyric from the Talking Heads record Remain in Light: “born under punches, I’m a tumbler, I’m a government man.” When Chiarella was working for the state of New Mexico before he went to graduate school for his MFA in writing at Bard College, he thought the idea of being a “company person” was absurd. And when he returned to Santa Fe to work for Meow Wolf after he completed his degree, he thought, “Shouldn’t this be abhorrent or really difficult? I don’t want to be a company person. I was supposed to be this free, independent artist. But really the thought is like, I’m working with all of my friends. They have managed to construct a company that is this shell, this thing that allows us to make the work that we want to make.”

It’s impossible to discuss Meow Wolf right now, to think about the work they make and their impact on the contemporary art world, both in Santa Fe and elsewhere, without discussing the glaring, obvious truth: they are wildly financially successful, at least by art-collective standards. The collective formed in 2008 but had all but disbanded by 2013. Although the installations they made, often out of repurposed materials or trash, were met with an enthusiastic response, they were sick of struggling to make ends meet as a ragtag nonprofit. Vince Kadlubek makes it clear that Meow Wolf’s decision to be a for-profit company was deliberate from the inception of the House of Eternal Return. He recounts seeing the vacant bowling alley, the future home of the House, and knowing that if they were going to make anything of the space, they should “do it as a business.” His “trump card,” as he called it, was an already interested investor, the writer George R.R. Martin. So when the collective began inviting artists to contribute to the House, it was with the understanding that Meow Wolf had adopted a business model, and artists should “work with this new reality of employment.”

It’s impossible to discuss Meow Wolf right now, to think about the work they make and their impact on the contemporary art world, both in Santa Fe and elsewhere, without discussing the glaring, obvious truth: they are wildly financially successful, at least by art-collective standards.

It might be easy to assume that artists would chafe at being called employees, but this doesn’t seem to have been the case. “Everyone wanted to [participate],” Kennedy explained, “because there aren’t any opportunities to do projects like this. Even in galleries, you can put pieces on the walls, but to actually get to do something as bizarre as most people wanted to do, the sort of things that people had been wanting to do for years,” was the draw. The financial security and collaborative nature of the House of Eternal Return ensured that artists would have the means and the skillsets available to them to execute a project that had been heretofore untenable.

The House of Eternal Return is not the first or only for-profit art space, and nonprofits aren’t somehow more pure or altruistic than for-profits. One only has to point to MoMA, with its shamelessly blockbuster exhibitions, long history of corporate sponsorship, prohibitive admission rates, and $145 million annual revenue to see that nonprofits are not always entirely above reproach.(4) Chiarella believes that the differences between Meow Wolf’s installations and more traditional art spaces are mostly superficial. He has studied the results of Meow Wolf’s financial analyst’s calculations of the cost per square foot of the House of Eternal Return, including materials and labor, as well as the costs for the temporary projects they design for festivals and other venues, and

then I think about… how much would someone pay at a gallery in Brooklyn for a square foot of canvas that’s been painted? And the prices are comparable. Maybe not to every gallery, but to me it’s funny to think about the kind of rhetoric that’s put around working in, say, an academically deemed acceptable gallery in a geographic location that’s gotten a stamp of approval, versus working in a company setting. The economics are essentially no different.

For Chiarella, the system under which Meow Wolf operates isn’t substantially different from the system that perpetuates a cycle of artistic trends via a symbiotic relationship between museums and elite MFA programs in the blue-chip art world. One implication of Chiarella’s logic, although he didn’t say it explicitly, is that since Meow Wolf is open about its financial motivations, the work they do is less tainted than that elitist system.

Meow Wolf’s organizational structure most closely resembles a start-up. At the top are eight officers, the original founders of Meow Wolf. Below this top tier, which is responsible for all the major aesthetic, branding, design, and financial decisions of the organization, is a tangle of Project Managers, Art Directors, and various Teams in charge of different aspects of implementing installations. There are also marketing and design staff, administrative assistants, as well as the public-facing desk workers in the lobby of the House of Eternal Return. Kennedy estimated that there are currently about 180 Meow Wolf employees, and roughly half of those are creatives who work on the actual building of the exhibits, but that number is changing all the time. As I write this, there are twenty positions open on the Meow Wolf website, whose salaries range from $35,000 to $100,000.

Kadlubek agrees that Meow Wolf more closely resembles a start-up than a more traditional art institution. During our meeting, he elaborated on what he characterized as a specifically Millennial relationship to capitalism:

I’ve never had a problem with capitalism as a whole. The way businesses have utilized capitalism is disturbing, and the way that the most powerful people within the capitalist structure have treated capitalism is disturbing. But the system itself allows for various types of usages. And I think that our generation, the Millennial generation, is way different than Gen-X in that way, is way different in the sense that we are willing to be pro-business. The progressive mindset is a pro-business mindset, and it is free-market and it is capitalist, with the understanding that that capitalism needs to be done socially responsibly, and that greed is the problem not capitalism, and those two can be separated out. Capitalism doesn’t just automatically mean greed…. We’re okay with capitalism, as long as we maintain social responsibility while we do it.

It’s worth noting that the misuses of capitalism that Kadlubek obliquely refers to include, but are not limited to, imperialism, colonialism, slavery, heteronormativity, mass incarceration, and massive environmental damage. These effects are indeed disturbing; they are also structural, imbricated in American culture, and as yet inescapable. Kadlubek’s statement strikes me, at this particular political and cultural moment in the United States, as a statement made from a place of privilege, and it’s difficult to argue that the Meow Wolf contingent is not currently enjoying a certain degree of privilege. The majority of their officers and employees are white, the ones I spoke to were well educated, and many of them also have securely middle-class incomes. Even Steve Jobs was once just a guy who dropped acid and wanted to unite the human race and change the world.

There are, however, tangible ways in which Meow Wolf seems to be making good on its promises to maintain social responsibility. Their non-profit, Chimera, is an education initiative that collaborates with New Mexico public schools. Meow Wolf artists lead workshops and design curricular modules to teach students to make and install art, handle materials, and think about their work in a larger social context. Chiarella, who currently serves as Chimera’s board chair, is especially fond of Omega Mart (2012), an installation that involved setting up a fake grocery store, complete with radio ads about a grand opening in Santa Fe, and having students stock the shelves with their own products. The concept behind Omega Mart also includes a pretty blatant critique of consumer culture, as Chiarella explained: “We used it as a platform to look closer at advertising strategies and strategies on packaging and package display, package design and the way people might be misled or manipulated by packaging materials, but in an easy-to-approach form.”

Mid-conversation, I often experienced moments of self-doubt where I felt a sort of paranoiac obligation, through no specific action from my interlocutor, to consider that these artists—members of a generation raised with an inherent knowledge of the perils of commercialism, the cynicism born of postmodernism, the political pitfalls of capitalism, and an optimism about technology that my Gen-X brain can’t fathom—may have beat the system. Is this even possible? Is that even the right question to ask?

Perhaps the most high-profile use of Meow Wolf’s philanthropy is its DIY Fund, a program that the collective established in the wake of the Ghost Ship fire in Oakland last December, in which thirty-six people lost their lives because the organizers of the event lacked access to a safe venue. The DIY Fund, which started at $100,000 but which Kadlubek plans to grow, will help independent arts and music spaces with infrastructure and other material needs to keep their spaces safe and operational. Kadlubek sees Meow Wolf’s involvement and commitment to supporting other independent arts organizations as an imperative to counter the political animosity toward the arts that has only increased since the Trump administration.

During my interviews with Kadlubek, Kennedy, and Chiarella, I was struck by a sort of utopian idealism inflected in their descriptions of every aspect of the organization, from producing the exhibits to the minutiae of administration. Mid-conversation, I often experienced moments of self-doubt where I felt a sort of paranoiac obligation, through no specific action from my interlocutor, to consider that these artists—members of a generation raised with an inherent knowledge of the perils of commercialism, the cynicism born of postmodernism, the political pitfalls of capitalism, and an optimism about technology that my Gen-X brain can’t fathom—may have beat the system. Is this even possible? Is that even the right question to ask? If this collective has achieved sustainability by building a pseudo-ironic corporation, perhaps that says more about the world we live in than about Meow Wolf itself.(5) In spite of the skepticism I harbor, and would harbor against any organization that has seemingly unfettered potential for growth, all the people at Meow Wolf I spoke to are also dedicated and serious about their work, and this is not an insignificant point. Their plans for expansion are highly ambitious, and they don’t seem to have taken for granted that they are in a position to execute their artistic ideas at a nearly limitless scale. But they also acknowledge that they are learning as they go, and Kennedy has no illusions about how much they have to learn. “Someone used the wonderful metaphor yesterday of building the plane as you’re flying it, which we’re doing,” she told me. “But during the build [of the House], we didn’t even know we were in a plane; we didn’t know we were off the ground, but we were flying.”

1. “Lightly plumed palms from the tropics mingled with the leafy crowns of the five-hundred-year-old elms; and within this enchanted forest the decorators arranged masterpieces of plastic art, statuary, large bronzes, and specimens of other artworks… Overall, it seemed a wonderland, appealing more to imagination than to intellect.” Julius Lessing on The Crystal Palace (1900), quoted by Walter Benjamin in The Arcades Project (1927-1940).

2. “Most adults who say they like Disney World report the fun they have ‘people watching.’ This is probably the most important and yet most understudied phenomena of mass culture. People watching is an active means for coping with boredom, fatigue, stress, and duress associated with mass culture.” The Project on Disney, in their book Inside the Mouse: Work and Play at Disney World (1995).

3.“The presence and circulation of a representation (taught by preachers, educators, and popularizers as the key to socioeconomic advancement) tells us nothing about what it is for users. We must first analyze its manipulation by users who are not its makers. Only then can we gauge the difference or similarity between the production of the image and the secondary production hidden in the process of its utilization.” Michel de Certeau, from his book The Practice of Everyday Life (1984).

4.“Although museum boards in the United States have traditionally been linked to the power elite of the country, the tax-deductible infusion of corporate money as a deliberate means to create popular consent adds a new dimension to institutions’ ideological bias. It is at the risk of both his or her professional career and the future viability of the institution that a museum official stages activities that are likely to alienate corporate donors.” Hans Haacke, from his essay “Working Conditions” (1979-1980).

5 “Amusement and all the other elements of the culture industry existed long before the industry itself. Now they have been taken over from above and brought fully up to date… ”Light” art as such, entertainment, is not a form of decadence. Those who deplore it as a betrayal of the ideal of pure expression harbor illusions about society.” Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, from “Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in their book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1940-1950).