Tamarind Institute, 2500 Central Avenue, Albuquerque

The Tamarind Institute has been operating since 1960; in 1970, Albuquerque became its home base. It is hard to imagine American printmaking, certainly lithography, before its existence when artists who wished to create a lithograph had to turn to Europe to find a capable print shop. Its founding director, June Wayne, intended for the Institute (originally the Tamarind Lithography Workshop) to accomplish several goals: train new master printers through an apprenticeship program; foster an environment of collaboration between printer and artist; revitalize the lithography tradition in the United States; and elevate the medium of lithography to a fine art through the production of technically superior and artistically innovative prints. Tamarind Institute’s impact on lithography, in particular, and the printmaking world at large, cannot be overstated. The success of such a visionary mission for Tamarind must be credited to Wayne’s ambition, but also owes much to Clinton Adams, Tamarind’s first associate director, and Garo Antreasian, its first Technical Director. It is exceedingly appropriate and surprising to note that the most comprehensive exhibition of Antreasian’s prints to be shown in New Mexico would be held in the Tamarind Institute’s gallery. Appropriate, due to the artist and printer’s incalculable contribution to Tamarind’s standing as a titan in the print world, and surprising only because such an exhibition has not occurred before.

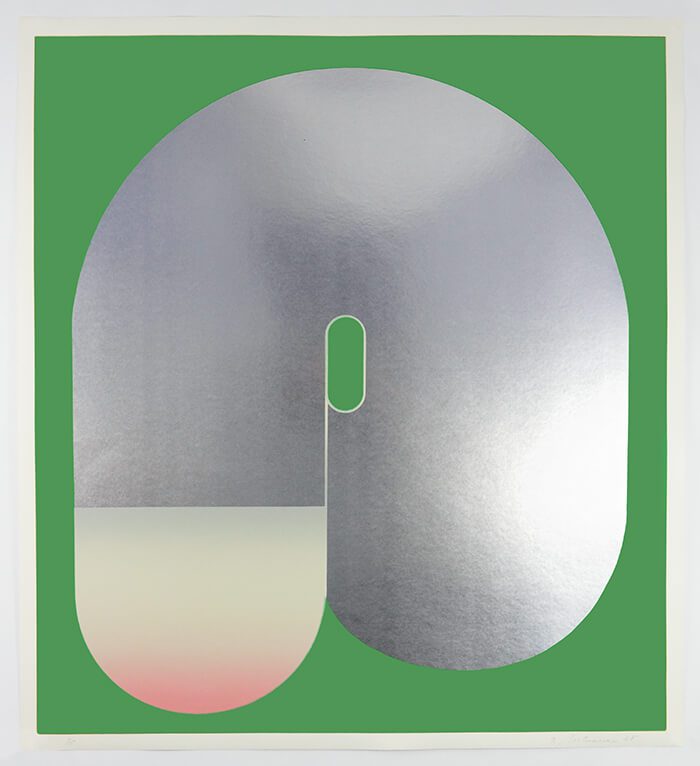

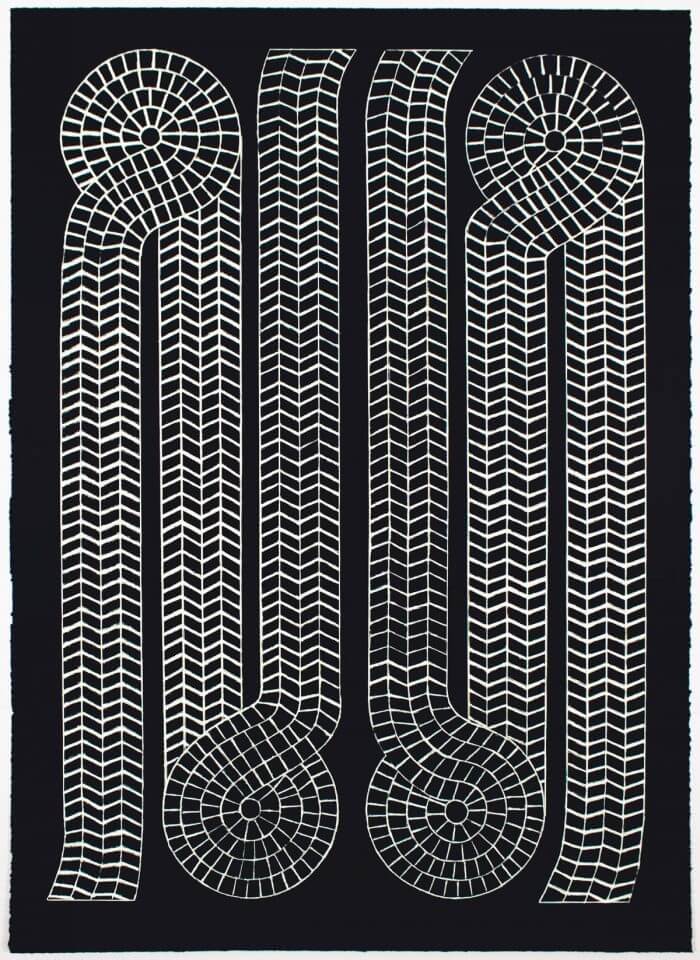

The placement of solid, curvilinear forms against vibrantly colored backgrounds, graphic patterns, and suggestions of a grid are hallmarks of Antreasian’s style.

Viewed as a mini retrospective, Tamarind Institute’s current exhibition (extended through March 10), Garo Antreasian: Innovation in Print, serves two roles; it is both a technical manual for printmakers and a visual timeline of Antreasian’s development as an artist. The fact that a student of printmaking could spend hours mulling over the complexity of the selected works, contemplating, “how did he do that?” and an art lover could spend equal time marveling at Antreasian’s sensitivity to color and form are both a testament to the printer/artist’s talents and evidence of how far lithography has come in the past sixty years as a fine arts medium. While the exhibition features prints from throughout Antreasian’s six decade career, works from two series particularly stand out: his “Silver Suite,” named so because of the incorporation of metallic silver paper, and the “Quantum” series, which prominently features the use of colorblends known as a “rainbow roll.” Both the printing on metallic papers and the rainbow roll are Antreasian’s innovations and prime examples of his neverending experimentation. The placement of solid, curvilinear forms against vibrantly colored backgrounds, graphic patterns, and suggestions of a grid are hallmarks of Antreasian’s style: one that places him firmly with his contemporaries who made their mark in the midst of abstraction from the late 1960s to 1980s, particularly Ellsworth Kelly, Richard Diebenkorn, and Ad Reinhardt. Antreasian is clearly influenced by the color schemes and slick forms of graphic design. Like the best commercial packaging, his prints vibrate and glow, inviting viewers to look closer.

What is unique about the Tamarind Institute’s exhibition of Garo Antreasian’s prints is the connection between the artist and venue. Antreasian was instrumental in developing both the printing training program at Tamarind and the printmaking department at the University of New Mexico, and the exhibition of his works in the Tamarind gallery offers a chance to reflect with pride on the tie between modern lithography and New Mexico. Additionally, the exhibition serves as a reminder that many printers, often employed to execute another artist’s vision, are themselves artists in their own right. Antreasian’s mastery as both artist and technician are evidenced equally in the color shifts of his “Quantum” prints and in the text of another work’s wall label that reads: “Color lithograph drawn with asphaltum solids and gum stencils on aluminum plates and printed in seven runs and reinforced with hand coloring,” (Untitled, 1978). The opportunity to engage these works as visually stunning and technically astounding examples of lithography is a tribute to Antreasian’s creative and curious spirit. And at nearly 95 years old, he’s still innovating.