Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism at the Albuquerque Museum includes a kaleidoscope of work from iconic Mexican artists.

February 6—May 2, 2021

Albuquerque Museum of Art and History, Albuquerque

The Mexican painter Frida Kahlo has become such an icon that she is immune from criticism for all practical purposes. Her paintings, her turbulent relationship with her husband Diego Rivera, and her image have taken hold in the popular imagination. There are books and novels on her, a Hollywood film (a photo of the actress Salma Hayek playing Frida is in this exhibition), countless posters, refrigerator magnets, and tattered bead curtains bearing her face. You can dress up as her for Halloween.

Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism is not an exhaustive overview of the three subjects in its title. It instead features work from the collection of a couple, Natasha and Jacques Gelman, and is naturally incomplete. If the viewer expects to see examples of Rivera’s greatest works, or a comprehensive look at the Mexican Modernists, they will be disappointed. Never mind, there is a kaleidoscope of good art here. The commonality between all of these artists is that they decided in the most patriotic way to make an art from their own country, imbued with qualities they considered native to Mexico.

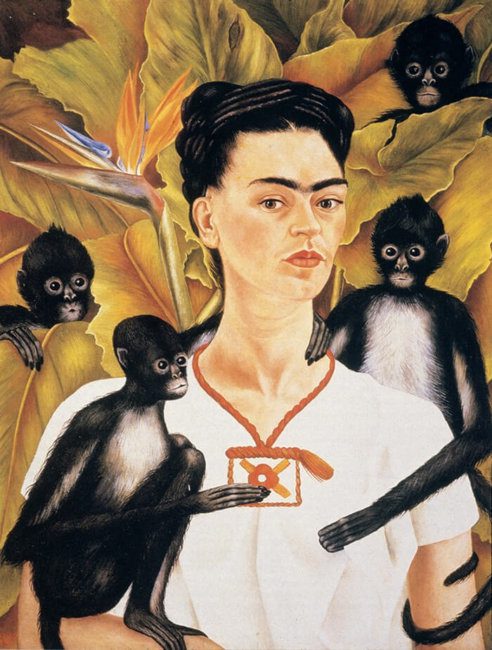

The show is mostly focused on Kahlo, who is indeed a fascinating subject. She made herself, with her striking face and the slight physical body which was the occasion of so much suffering—sickness, polio, bus accidents, surgeries, miscarriages—into an art object of her own. She was a beautiful woman with a unibrow and a faint mustache (which she exaggerates in her paintings) wearing traditional Mexican dress—even at an art opening for Picasso in New York. She looks amazing in each and every one of the many photographs of her in the exhibition. In a couple of the photos, Kahlo paints while Rivera (who was then far better known) stands behind her, apparently riveted. There are drawings, journals, costumes, and an entire wall of photos of objects associated with her, including her crutches and body corset.

Most importantly, there are her paintings, the reason why people might be interested in her crutches. The paintings look better in person than in reproduction (which is not always the case with famous art; see Matisse). The subjects of her work might seem claustrophobic: self-portraits, turning points in her life presented symbolically, images of Rivera, portraits of friends, still lifes of fruit. Sometimes they are painted in a naive way, sometimes with the classical technique that underpinned her work. The genius of these paintings, however, is that any person who looks at them can imagine not just Kahlo, but themselves in the crosshairs of life. They can imagine painting the difficulty of life into art, as she did. That is the reason why Frida Kahlo is an icon. She encourages the onlooker to participate both in her life and by extension, their own.

Rivera has a number of paintings in the show—of cheeky cacti, thoughtful children playing deep in their game, flower sellers. These are stylized by the techniques he had learned studying Cubism in Paris. My personal favorite of his in this show is The Healer (1943), a small gouache on paper of a folk healer at night, treating a child and surrounded by bluish-green rocks with the instruments of his craft. Although the paintings are weighty, they are not his best work, and he suffers by comparison. Rivera was a rockstar muralist, one of the world’s best then and now. For obvious reasons, you have to make a pilgrimage to see his work on site in Detroit, Mexico City, or San Francisco. There was an infamous incident in which Rivera’s mural “Man at the Crossroads”(1933), for the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza in New York, was destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller, who objected to the inclusion of the portrait of Vladimir Lenin, the Communist leader, in the painting. The mural has since been recreated. At the tail end of the exhibition, as you exit, there is a long reproduction of one of his murals in which you can see some of the color, variety, and grandeur of his frescoes.

There are a number of other interesting artists and photographers in the Mexican Modernist movement that are exhibited as well: the photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo and the painters Juan Soriano and Maria Izquierdo, to name just a few. Looking at their work, and at the exhibition as a whole, it made me wonder if we—or let me say I—am not still under the sway of a colonialist mindset in which only glamorous and monied centers of power, like New York or LA, or London or Seoul, can produce important art. Clearly in this exhibition, here was a group of people who decided to make art that was particular to them, their interests, and their place, and they transmuted that into wonderful art.