In the face of today’s sociopolitical climate, New Mexico museum practitioners plan for a brighter, more equitable future.

What does it mean to “future proof” a museum? How are museums’ and cultural institutions’ roles and responsibilities changing in the wake of the collective trauma we have all experienced in 2020? From the heartbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, to ongoing racial injustice and the ever-worsening climate crisis, the New Mexico Association of Museums’ (NMAM) Annual Conference faced these problems head-on and envisioned the ways in which New Mexico’s cultural workers can collaborate, innovate, and make positive change in their institutions and communities.

The conference opened with a keynote address from Denise Chávez. Best known as a writer, activist, and organizer of Las Cruces’ Border Books Festival, Chávez’s keynote was a story—the story of her life, her family, and her community, all rooted in la frontera and coraje, courage. She began by relaying two stories: one of her mother’s grandfather, from which she learned to “gather yourself up in dangerous times,” and the other of her mother’s uncle, who was once woken up by a rattler on his stomach—”these stories are a trajectory of my life.” Committed to preserving and sharing the cultural histories of the borderlands, Chávez is in the preliminary stages of founding a museum and archive center dedicated to Southern New Mexico, West Texas, and Northern Mexico—Museo de la Gente, to be located in the Mesquite District of Las Cruces, on the Camino Real. In discussing how to open and sustain a community-based cultural institution, she asked us all to consider:

“Who are we running from, but ourselves? It is important to know why we are running, what we are running from, and where we need to go. It is important to ask ourselves the hard questions. Is my work authentic? Is it real? What does it matter to me, and to others? […] May we confront the darkness of our times, the loss of many lives, the caging of our children and families, the devastation of our land and environment, with resiliency and strength. May we confront that rattler in our stomach and in our hearts.”

Calling for accountability, strength, and coraje, Chávez asks us to remember how special “our world” of New Mexico is—”even if we’ve left, it will never leave us. We are all New Mexicans in our core, in our being, and it is up to us to preserve the beauty and integrity of our landscape and our culture.”

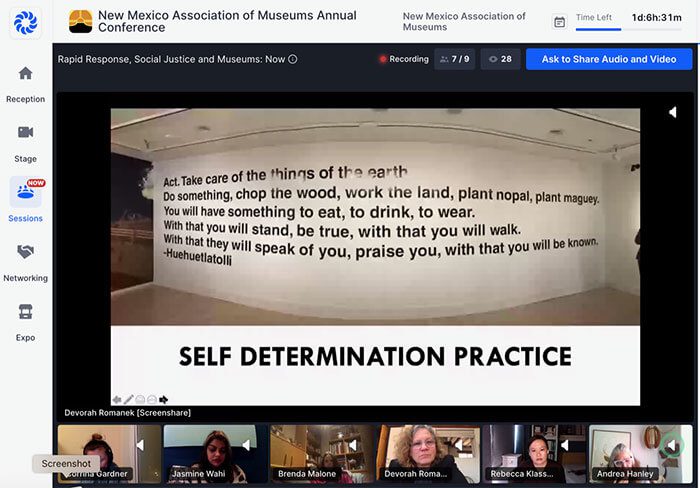

Building on Chávez’s call, one of the conference’s most tangibly applicable and energizing panels was “Rapid Response, Social Justice, and Museums: Now,” organized and moderated by Dr. Devorah Romanek (Curator of Exhibits & Director of Interpretation, Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico). With presentations from museum workers around the globe, the discussion explored how museums, through both acquisitions and exhibitions, can best preserve and document the current sociopolitical moment. Here, the New York Historical Society’s Rebecca Klassen (Associate Curator of Material Culture, NYHS) discussed her work with rapid-response collecting, which significantly expanded in recent years with the Women’s March in 2017, March for Our Lives in 2018, the Climate Strike in 2019, and the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020. Similarly, the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Corrina Gardner (Senior Curator of Design and Digital, V&A), discussed her own rapid-response program, which included the purchase of the first Lego set to show women in non-gendered settings. Similarly, Brenda Malone (Curator, National Museum of Ireland) talked through the challenges of contemporary collecting in a federally-run institution, and in the face of Ireland’s historic conservatism. Bringing the conversation back home to New Mexico, Andrea Hanley (Chief Curator, Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian [Diné]) discussed how Indigenous artists, “by their very nature, think outside of the box,” and asked us to investigate the ways in which Native art uniquely speaks to social justice and contemporary politics.

To close, Romanek provided an overview of recent projects at the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, including exhibitions on the gun violence epidemic, Indigenous activism, and water management in New Mexico. Here, Jasmine Wahi (Holly Block Social Justice Curator, The Bronx Museum of the Arts) noted that “visibility is a primary tenant of social justice,” and argued that “resistance can come in the form of the mundane, the normal, and in moments of joy.” And it is through this that museums and exhibitions have the power to reframe conversations about today’s particular moment.

How can institutions become generative spaces for storytelling, community dialogue, and healing? And fundamentally, how can we hold museums accountable?

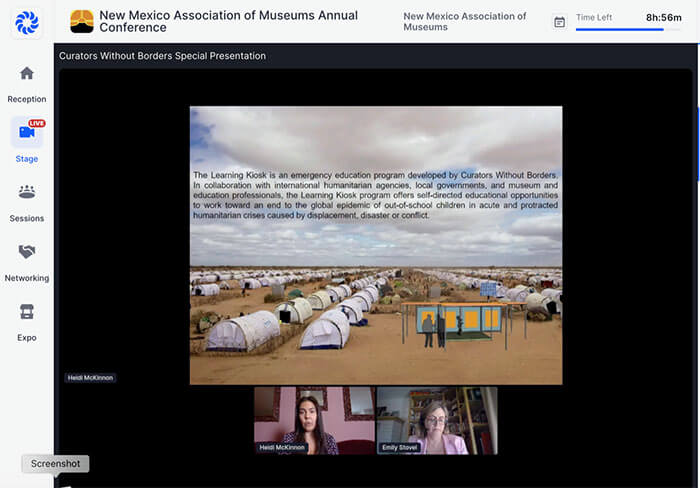

Broader conversations about the role of the museum in the 21st century also permeated the conference. In a plenary session, Curators Without Borders’s Heidi McKinnon (Executive Director, CWB) discussed the responsibility that museums have in humanitarian crises, asking us to critically reflect on how museum research and collections can change lives through emergency outreach—“how do you maintain and participate in your own cultural heritage when you are forcibly displaced from your homeland?” And Dr. Susan Guyette’s (Director, Santa Fe Planning and Research [Métis–Micmac & Acadian French]) presentation focused on the ways in which museums can become more community-oriented by asking us to reconsider the fundamental function and value of the cultural institution. For Guyette, honoring local “New Mexican values” (which she placed in opposition to “mainstream American values”) is fundamental to this necessary reconfiguration—community over individualism, cooperation over competition, generosity over accumulation, and conservation over consumption. How can these reorientations help us re-imagine what a museum is, can, and should be?

In addition to being more accessible to professionals throughout the state, the virtual conference format allowed for creative additions to the traditional conference experience, such as yoga sessions, tea giveaways, and digital daycare. Reflecting on NMAM’s digital pivot, incoming President and Conference Program Chair Ryan Flahive (Archivist, Institute of American Indian Arts) explained that “[w]hile most museum organizations chose to cancel their annual meetings or run them on systems like Zoom, the 2020 NMAM virtual conference was a leap of faith into the unknown. […] This conference empowers NMAM to embrace virtual technology and offer more online trainings, professional development opportunities, and networking opportunities for New Mexico’s cultural professionals.”

After almost forty sessions, workshops, and special programs, the conference closed with a call to action. Mike Murawski (Co-Producer, Museums Are Not Neutral), Jaclyn Roessel (Director, Decolonized Futures and Radical Dreams, U.S. Department of Arts and Culture [Diné]), Winoka Yepa (Senior Manager of Museum Education, IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts [Diné]), and Elena Gonzales (Independent Scholar) pushed attendees to think deeply and critically about our own agency within the current moment. How can we, as cultural professionals, best work with communities, build trust, and repair the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism? How can museums become more human-centered, rather than object- or donor-centered? How can institutions become generative spaces for storytelling, community dialogue, and healing? And fundamentally, how can we hold museums accountable?

Ending on a cautiously optimistic note, Murawski reflected that institutional, cultural, and personal “messiness” can often be positive agents for change—“in moments in fracture, there are opportunities to sew a different type of future.”