Once upon a time, I was teaching a “job readiness” class for refugees and immigrants in Seattle. I sat at an oblong table with a small group of students whom I loved and suspected myself incapable of truly helping (especially when it came to the matter of job readiness, which has never been my strong point). Together we stumbled through a set of standard job interview questions. Someone—I don’t remember if it was me or another student—looked at the woman to my right and said, “Halima*. Where will you be in five years?”

Halima flicked her hand through the space in front of her as if to bat away this idiotic question.

“God only knows,” she said.

She’d fled civil war in Somalia, living more than a year in a crowded camp in Nairobi. She’d lost siblings, cousins, parents, her home—her entire world. She knew her answer was “wrong,” but she could not—would not—even perform certainty in so distant a future.

That exchange has come back to me in recent months because Halima’s answer suddenly seems the correct answer to every question that can be asked. When will the planned show at SITE Santa Fe open? Which local restaurants will survive the pandemic? Which shops, which livelihoods will endure? Who, and how many, will die tomorrow? How will the nurses and doctors recover from their trauma? When will this end—and, when it does, what kind of people will we be?

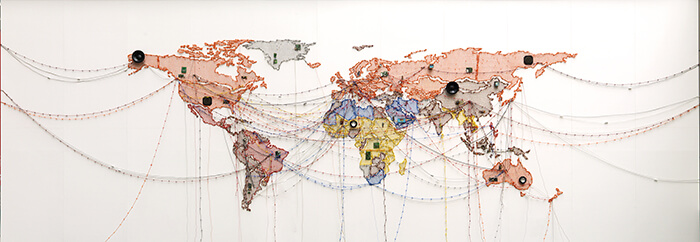

Displaced: Contemporary Artists Confront the Global Refugee Crisis, like all the exhibitions around the world that no one can currently see (or that can be seen only on the diminished faces of computer screens), was conceived before the novel coronavirus adapted to the human body and started to spread through human networks. But the subject of the show is intricately connected to those very networks. It’s difficult, now, to look at the barbed cables mapping migration and trade routes in Reena Saini Kallat’s Woven Chronicles (2015) and not think of microbes.

My first encounter with the show was in February. There was snow on the ground, and the coronavirus was way off in Wuhan. I’d dashed from an artist talk to get to SITElab before the gallery closed, not because I feared it would close forever, but because I was anxious to see the work that had just gone up—the first of what would comprise Displaced.

Leavings/Belongings (2016–ongoing) is made with fabric gathered from around the globe. In SITElab’s front room, a huge net hangs from the ceiling, filled with bundles of fabric created by artists Harriet Bart and Yu-Wen Wu in collaboration with refugee women who have made their homes in New Mexico and other U.S. states. Notes are sewn to some of the bundles, some detailed, some simple: “I am from Somalia. I have eight children. God blas [sic] you.”

Discussion of art is conventionally centered on the artist, and it’s natural to think about the care of these two artists, taking the time and making the space to collaborate with the subjects of their work. But these refugee women’s sharing of their experiences and aesthetics is also an act of great generosity.

The red thread that represents a bloodline—a woman explaining how, after hundreds of years and stories, she is the only one left.

In the backroom, I stand entranced, watching the words and images of stories, the names of so many countries, slip across a screen while the music of women’s voices fills me. The voices are layered—sometimes clear, in English; sometimes difficult, audible only in fragments, or spoken in a language I don’t understand. The thin horizon of the ocean morphs into a full view of the sea. It looks dangerous, intimidating. There is a story about people drowning, recounted by a woman who survived. Some of the stories are about arrival. Some are about departure. Some are about memory. Some are wishes for an end to war. Some of the women explain their choices in the making of the bundles. The red thread that represents a bloodline—a woman explaining how, after hundreds of years and stories, she is the only one left.

Leaving the gallery that day, I sat down on one of the benches to jot down a few notes, to let my breath catch up to my heart, and noticed that someone had hung plastic bags stuffed with knit hats and scarves all along the walkway. Tied to each bag was a message of love and Christian faith. Just before I left, a man came along the path, pulling down one bag after another. Was he taking them for himself? To resell, turning generosity to profit? Or was he planning to distribute to others in need?

Cancellations and closures began shortly thereafter, and displaced seems like the opposite of what I have been for most of the socially distanced weeks since. When I finally visit SITE’s main gallery in late April, the drive to Santa Fe feels like a significant journey. I’ve been walking and running in circles close to home for over a month, minimizing trips to supermarkets as much to avoid the empty shelves and suspicious glances as to avoid the virus itself. Re-open dates, for this gallery and for everything, remain tentative, uncertain. So when I see Hew Locke’s boats, meant as a meditation on the centrality of migration to human history, I feel longing. I want to climb into one of those boats and sail away.

I know how lucky I am. I know, too, that while displacement may begin with movement, with motion, confinement is quintessential to the refugee experience. Asylees who try to cross the southern border to enter the U.S. are, if they are allowed to enter at all (the president is currently defending new policies to send asylees to Honduras and Guatemala), promptly incarcerated in private prisons like the Cibola Corrections Center.

When I see Hew Locke’s boats, meant as a meditation on the centrality of migration to human history, I feel longing. I want to climb into one of those boats and sail away.

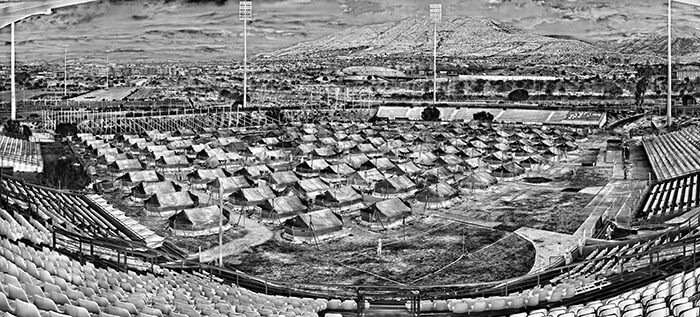

The camps in Richard Mosse’s panoramic photographs are not prisons, but if you look closely, you can see the barbed wire encircling the perimeter. From a distance, the stills from Heat Map (2016) look like they’ve been digitally solarized; light and dark seem to be inverted, and silver is a dominant tone. But the lines are crisp. To make these images, Mosse used military-grade thermal surveillance technology: what’s brightest is heat. Bodies, fire, engines. This technique evokes warfare—and the U.S. border. The same technology is used in the tethered aerostat radar systems positioned along the U.S.-Mexico border, like the one housed in the $4-million-dollar blimp that is visible from the outskirts of Marfa, in West Texas.

Mosse’s stills at SITE center on refugee camps in southern Europe: tents set up at a stadium in Athens, shipping containers converted to temporary residences at a port. The image that haunts me, is not, surprisingly, the one at the port, with guys playing volleyball on cement while, across the barricade, trucks line up to transport containers full of product. What stays with me is a panorama of an informal camp set up on a beach. The image is dark but for a couple of campfires and the heat of human bodies—a pair walking together, a group at a bench, someone in a tent. A vague shape is visible, exposed, in one of the outhouses atop the bluff. The image reveals how infrared can dehumanize, render faceless, and blur the line between enemy and outsider, enemy and refugee, enemy and immigrant.

Candace Breitz’s work seems to call attention to the inverse—the erasure produced through the appropriation of others’ stories. The smoothing and streamlining that results from adapting a life to a screenplay, casting a famous actor to play the part. Breitz gives the actors an enormous screen, and their faces are intended to be the first that viewers of Love Story (2016) see. Six refugee stories have been mined for the choicest lines and given to these stars. “Shows like Lost and Survivor really helped my listening skills,” Alec Baldwin says, affecting the earnestness of his role but also knowing to play the line for laughs.

Top: Shabeena Francis Saveri, Sarah Ezzat Mardini, Mamy Maloba Langa / Bottom: José Maria João, Farah Abdi Mohamed, Luis Ernesto Nava Molero. 7-channel installation, 7 hard drives. Commissioned by the National Gallery of Victoria (Melbourne), Outset Germany (Berlin), and the Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg.

I know the actual interviews are hours-long, but I want to sit down in the next room and watch at least one all the way through. I want to commit even to the boring parts, the extraneous details, the repetition, the revelation of prejudices and tics and imperfections. “As a refugee,” Julianne Moore says on the big screen, “I don’t want anyone to pity or feel sorry for me.” I want to hear the refugee herself say that on one of the six smaller screens; I want her context. But the day I visit, the headphones sit in a heap on a table behind me, waiting to be figured out, so I can only walk from screen to screen, my sloppily-tied face mask causing my breath to fog up my glasses, studying the gestures and expressions of the refugees telling their stories.

Back when I was teaching English and ostensibly helping prepare refugees for the future, I had similar experiences of wanting to hear more than I could. Sometimes it was due to language, but often it was due to trauma. Stories of trauma are risky to tell. They demand courage, trust, reciprocity.

That’s why the gallery seems an uncomfortable, or at least incomplete, space for Guadalupe Maravilla’s strange, beautiful Disease Thrower #10 (2011-20). Both shrine and headdress, the assemblage calls out to be worn, performed, and its accompanying gong played. At center is a clear plastic mask, which I can’t help but compare to the PPE that has been in such short supply at hospitals. More than ever, the mask evokes the artist’s vulnerability—but also his strength. Maravilla crossed the border as a boy, traveling with a coyote from war-torn El Salvador, and if there is an activist element to his work, what he advocates is healing. In Los Purifiers (2019), the gongs on Maravilla’s headdress-shrines are played in a sound-healing session. The Miami performance was a tribute to victims of two mass shootings (including the racially motivated shooting at a Walmart in El Paso in 2019) and to the 680 people deported from Mississippi in the largest single-state immigration raid in U.S. history.

Hostile Terrain 94, part of the Undocumented Migration Project, is also an invitation to bear witness. Jason de Léon, who conceived the global installation, told me that stories were what inspired his detour from the conventional anthropological work that he started his career with. Doing research in Latin America, he got to know people who were digging ditches for archaeologists, many of whom were either getting ready to migrate or had family who were migrating. During his research, he started becoming more interested in their stories than in what was coming out of the ground. He shifted his focus to the “archaeology of the contemporary,” analyzing some thirty-five thousand material artifacts “in the field,” which, for De Léon, had become migrant pathways in the Sonoran Desert.

The title of the piece refers to a border patrol strategy known as “prevention through deterrence,” which since 1994 has deliberately funneled migrants away from urban border crossings and into the wilderness, characterized in policy documents as “hostile terrain.” In his book, De Léon analyzes the evolution in language used to describe this strategy, observing how the explicit goal of increasing migrant deaths has been reframed over time. By 2010, the tragedy of migrants dying in the desert was presented as if it were an unintended consequence and not key to the policy’s design.

Like Maravilla with his sound therapy, De Léon seeks the participation of his audience. But whereas Maravilla reaches toward those who have known trauma and need healing, De Léon extends the invitation to those who may be more familiar with the statistics (and polemics) of immigration than the experience itself.

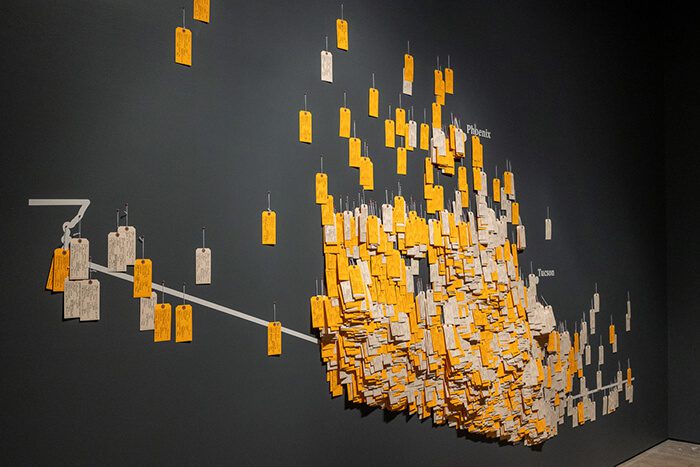

The invitation is this: Come in. Note the simple map of the U.S.-Mexico border on the wall across from you. Look at the photos—one is a stretch of the fence that, as you take your seat, is being, or has just been, extended through southern New Mexico (yes, this was deemed essential business during the pandemic). Now, read the instructions. Take a toe tag from the box, and follow the instructions to fill it out. Name (if there is one), age, sex, cause of death (if it’s known). Latitude, longitude. On one of the sample tags, “body condition” is described as “skeletonization with mummification.”

De Léon mentions that he recoiled the first time he was asked to do an exhibition. He was conscious, as an anthropologist, of the problematic history of putting people on display. And as he put up installations of artifacts gathered from the migrant trails for State of Exception (2013), he saw others begin to do similar work, disconnecting the objects from the people who’d left them behind. That, along with an online map of migrant deaths maintained by Humane Borders, ultimately inspired Hostile Terrain. For De Léon, “the act of writing out the names is a way to breathe life into these toe tags and remember these individuals.”

After all the tags have been filled out and pinned to the map—there are 3,200—the installation was to move to the Center for Contemporary Arts, opening the first of more than one hundred exhibitions around the world. Now, in collaboration with the School for Advanced Research, Hostile Terrain 94 will launch digitally on July 17, with other online programming to follow. The physical installation debuts at SITE Santa Fe later this summer.

In late April, the president issued an executive order demanding that meatpacking plants stay open, or re-open, regardless of the health of their workers or the threat of escalating coronavirus outbreaks in their cramped, already terrible workspace. Many of those the president has declared utterly essential to U.S. supply chains are immigrants and refugees. Farmworkers, here and in Europe, are at great risk of contracting the virus. Refugee programs are halted and outbreaks in camps could be catastrophic. Meanwhile, the mastermind of the U.S. president’s immigration policies is scheming to make temporary changes permanent, scapegoating immigrants as vectors of disease, and spinning the coronavirus to justify deporting unaccompanied minors and asylees. But SARS-CoV-2 didn’t travel to the U.S. in the bodies of Central American children; it flew business class. It flew coach from Europe, with its hosts’ passports in hand.

I don’t know where I’ll be in five years, or where you’ll be. But I hope that not too long after reading this, you’re able to experience, in person, Cannupa Hanska Luger’s Ancestral Future Technologies: We Survive You (2020). The installation riffs on the old ethnographic dioramas of American Indians, but here, instead of depicting Indigenous peoples as they were, or might have been, before their land was stolen, Luger hybridizes the ancestral and the sci-fi. There’s a TIPI (transportable intergenerational protection infrastructure) and a van (a repurposed archaic technology vehicle) that has been plastered with stucco or earth. The VR component wasn’t hooked up yet when I visited, but maybe, by the time you visit, it will be. It’s an Empathy Interface meant to help people connect to non-human species.

In a sense, the cumulative works at Displaced are another kind of Empathy Interface—one helping humans understand their relationship to other humans. Let’s learn how to use it.

*this is a pseudonym to respect the anonymity of the individual in question