Las Cruces–based artist Eva Gabriella Flynn’s meticulous maps and flags hover in an uncertain space between two nations, to playful and political effect.

Eva Gabriella Flynn is slowly killing her new neighbors’ cacti. Or rather, the cochineal insects she’s cultivating in her own cactus patch for the red pigment they produce have hopped the property line. She spots a wayward colony of the tiny nopal vampires through her home studio window in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and plans an apology visit.

Flynn’s explanation: “Cochineal will travel with the wind; they don’t fly too much.” The bugs’ delicate wings keep them afloat as they swirl toward the next cactus pad. If you were omniscient, you could trace their rippling dissemination back to a co-evolutionary coupling with their host plants—long before property lines, or the U.S.-Mexico borderline.

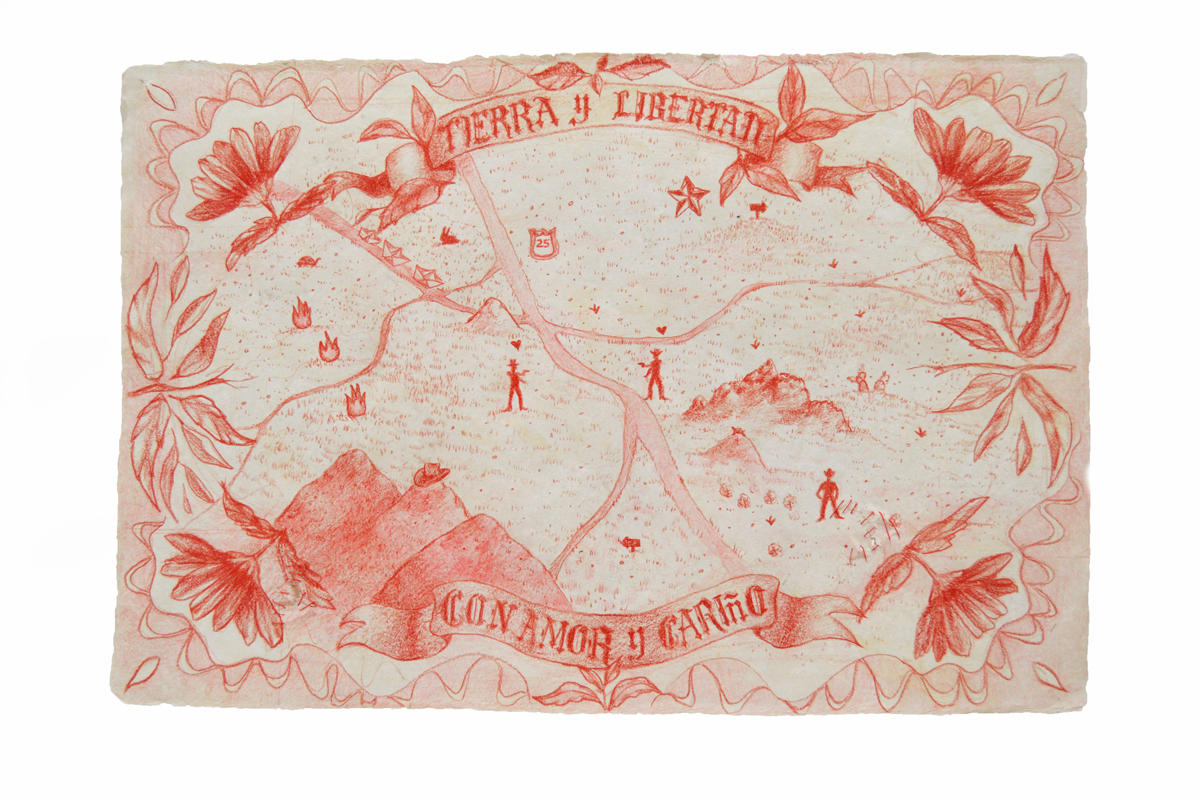

Clairvoyants profess that “the veil is thin” between our plane and others. Flynn’s portrayals of the borderlands are similarly mingled, and her transitional veils are fantastical flags and maps that flutter somewhere within a two-hundred-mile radius of the dividing line. Despite their meticulous material and pictorial details, it’s hard to tell which side the artworks—or their maker—are on.

Bottles and containers lining a shelf in Flynn’s studio bear a desert gradient: cochineal red, onion-skin yellow, pecan-shell brown. She’s still testing natural formulas to vividly activate her abstract flag designs, an “urban foraging” practice that intensified during a recent fellowship with the multifaceted community support organization La Semilla Food Center.

Spending time in different parts of the Southwest, you realize there is this really large, shared experience of growing up here.

Flynn’s nationless flags are meant to reflect common impressions of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran Deserts, which are split by the border. “Spending time in different parts of the Southwest, you realize there is this really large, shared experience of growing up here,” she says. “These same things are happening, again and again, across the deserts.”

The patchwork compositions are conceptually linked to Flynn’s long-running painting series of fragmented portraits, which she says explore her “inability to reconcile a body or space in just one location.”

You could also interpret them as Swiss in spirit, considering that Flynn’s mother is a Mexican immigrant and her father is a retired senior chief prosecutor for the Department of Homeland Security. “The personal is political, and I mean it very seriously,” says Flynn. Her now-divorced parents’ arguments “paralleled” the tensions between their native lands.

Flynn was born in Wyoming in 1995, and the family landed in San Diego soon after. One of her earliest memories is of a U.S. Border Patrol agent asking where home is, and not knowing how to respond. When she was three, her mother told her that if she dropped a paper boat down a San Diego storm drain it would voyage to Mexico. She started sending notes to her Mexican cousins.

“It was a whimsical, completely naïve way of understanding how borders work, or even how the sewage system works,” Flynn says. Like much childhood logic, her belief in the story wasn’t technically correct but it is revelatory. The borderlands of her youth—when she was around twelve, her newly single mother moved them to Las Cruces to live closer to their family in Chihuahua—were miraculously permeable.

“I remember crossing into Tijuana because my family was like, let’s be festive,” Flynn recalls. “Let’s have lobster on Thursday, let’s get a piñata for your birthday, my mom would go get her eyebrows threaded. Then 9/11 happened, and suddenly it took three hours to cross. [In El Paso], you could see the wall literally grow.”

At a formidable drafting table she inherited from her stepfather, who was a Boeing draftsman-turned-artist, Flynn sends paper boats and airplanes (“funny little underdogs”) sailing through hand-drawn maps of this contested space. They dodge mushroom clouds, tangle with majestic wildlife, and catch the tailwind of her mom’s beloved VW Beetle. They survey Looney Tunes scenery and key battles of the Mexican-American War.

This is the whirling multicultural carousel of Flynn’s childhood, packaged as a parody of tourist ephemera that she hopes will trigger cascading personal associations of the Southwest in viewers. “It feels like a satisfying itch to scratch, making up these worlds [that are] maybe in the future, where these borders don’t exist, or maybe in the past, where they did not exist,” Flynn says.

It’s a surreal thing to have your everyday experiences be theorized, conceptualized.

She is systematic in her drawing process, composing the maps “like a book, left to right, and I work my way across.” By crashing all of this iconography of the borderlands together, Flynn is confronting old myths and muddying up ostensibly progressive (and often strangely detached) new theories of the borderlands that surrounded her in graduate school at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

“It’s a surreal thing to have your everyday experiences be theorized, conceptualized,” says Flynn of her MFA years. “This is a beautiful and romanticized place that is constantly written about, constantly in discussion. It’s politicized, fetishized, parodied—over and over.” In a particularly jarring moment, a British professor attended a studio visit with Flynn wearing an oversized Western belt buckle, a hard-earned social signifier of Chicano ranch culture.

Flynn graduated and returned to Las Cruces in 2021. She now works in museum education at New Mexico State University, her undergraduate alma mater, a majority-Latinx institution that established a Chicano/a Studies program just five years ago. Her work with students and community members at NMSU stirs ideas that further her own practice.

“The artists that my NMSU professors told me to reference were mostly white men,” says Flynn. “Which is fine, but it had nothing to do with this connection to place, of culture and ethnicity, of understanding what makes the borderlands a truly unique region. Now I can say [to the students], ‘Do you know about the Chicano movement?’”