Phoenix-based artist Estrella Esquilín talks about her evolving studio practice, in which community is as important as the construction materials and experimental animation she uses to address identity and place.

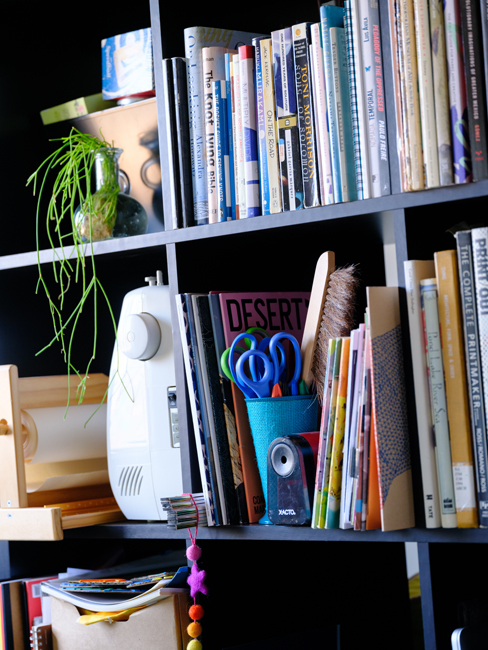

Inside the Phoenix home that artist Estrella Esquilín shares with her partner and their pets, there’s a small room that serves as her art studio. The space is clearly organized for efficiency yet exudes an aura of warmth. The sun shines in through a window where her cat often sits, not far from the table where Esquilín uses her laptop to work on her new series of low-relief sculptures suggestive of land and sea, which she creates with cyanotype prints on birch plywood and sheets of acetate. A small MIDI keyboard she uses to make soundscapes sits on another table, below a knotted net hanging on the wall.

Esquilín was born in Puerto Rico, an island that’s reflected in both her materials and forms. Several of her pieces combine building materials such as lumber, which she often uses to address systems of oppression or barriers between people, with natural elements and found objects. “I identify as a person of the African diaspora and a Caribbean person,” she explains. “I live in the Sonoran Desert, but I feel the ancient seas in the formations they created in the painted desert.”

Ideas related to land and place are central to Esquilín’s art practice, yet those ideas and the ways she manifests them have shifted over time. Now thirty-eight, the artist recounts years spent working in arts administration, where she fought to change systems and spaces created by and for others. Esquilín left her job in late 2022, which has given her more time for art, and a fresh perspective. “My work has always been rooted in my lived experience, but I want to be fueled by curiosity and joy instead of anger and righteous indignation,” she says.

Esquilín was raised in Kansas City, Missouri, and moved to the Southwest to attend graduate school in 2012, earning an MFA from Arizona State University in 2015. She’s worked in several media, including prints, drawing, and collage. In early 2023, her wall and floor installation Head Above Water (2022), consisting of a panorama cyanotype on Arches paper, plastic tarp, sand, and sea salt, was exhibited at ASU Art Museum along with works by three additional Latinx artists in the Southwest exploring place and environmental destruction.

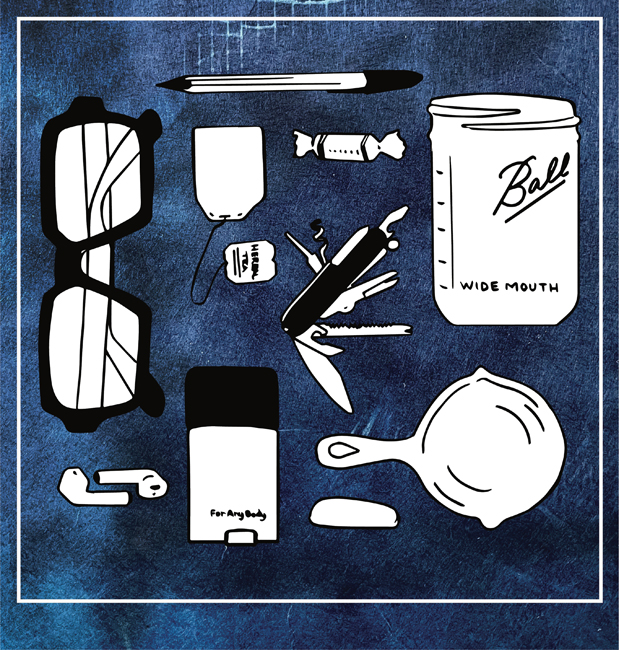

Today, Esquilín has several projects in development, including her Chingona Survival Kits launched during early COVID-19 lockdowns. The series highlights the objects several friends who “identify as femmes with various marginalized identities” found essential during the pandemic, which range from tampons to teabags. “The majority of my friends are creative people,” she says. “That community is such an important part of my life and my art practice.”

When I visited her studio in mid-June, Esquilín described her recent forays into experimental animation, including teaching herself to create both hand-drawn and stop-motion animation, as well as learning sound art techniques. “This is a way to build my own place,” Esquilín explains of her process, which includes taking walks where she records the environment, and recording the sound of her own body in various places. Sometimes she’ll capture herself breathing, or performing deliberate actions like clapping her hands. “I like to think of it as terraforming my own way of living and being in the world,” she says.

Esquilín’s first animation, Lassoing the Palazzo (2020), was shown in a large, street-facing window of a building in Phoenix’s Roosevelt Row arts district. Consisting of Esquilín’s illustration of a femme figure toppling a multi-level European-style building, the imagery served to “inspire the power to bring down other forces of oppression.”

As Esquilín’s cat vacillated between gingerly walking across studio work surfaces and pausing for a bit of lap time, the artist shared news of another change that could have a big impact on her creative practice. Esquilín is part of an artist residency program for the city of Tempe, which includes a studio space at a local elementary school. While looking forward to getting the keys, Esquilín reflected on what the added space might mean for the trajectory of her expanding body of work.

“I’ve had a small space for the last several years, so I’ve only been able to work on one or two projects at a time instead of building out an installation and having a place to think about time and scale,” she explains. Esquilín envisions doing more sculptural work and curator visits in the residency space, incorporating more play into her studio practice, and enjoying time with fellow artists in the program. “I like to have conversations about my process and get feedback and critiques of my work before it’s exhibited.”

Moving forward, Esquilín says she’ll continue to explore the experiences of immigrants and their descendants, people of color, and others who’ve been marginalized in American society. “My work has always been a self-portrait,” reflects Esquilín. “I make work for us.”