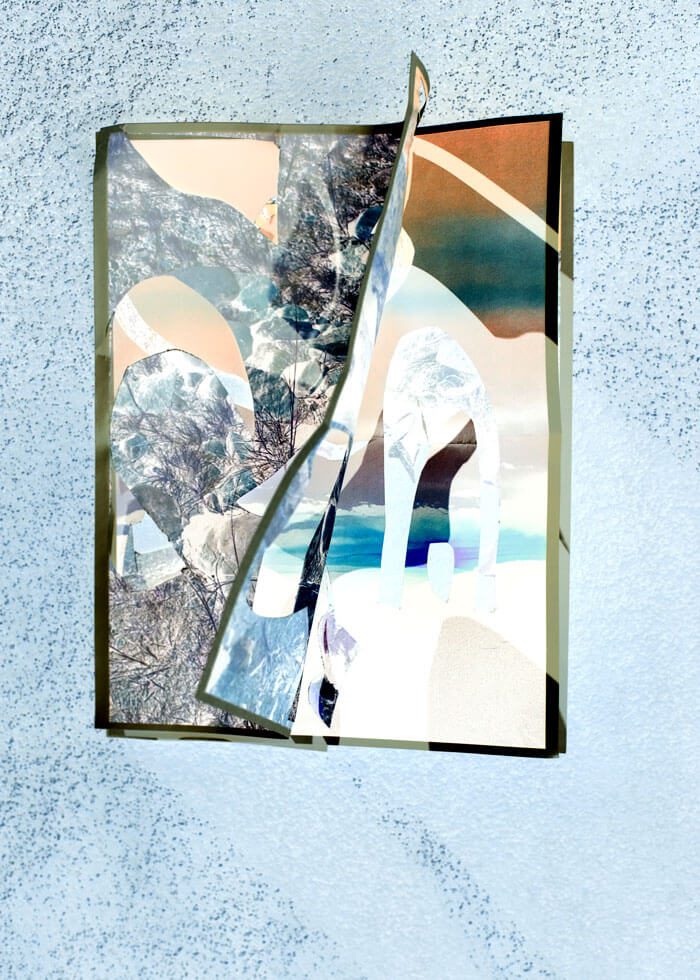

Emily Margarit Mason, composition I, 2018, photograph, 40 x 30 in. Courtesy No Land.

No Land, Santa Fe

October 27, 2018 – January 13, 2019

Recent clinical research on memory and its diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and dementia, reveals that the act of remembering sets off an electrical firestorm in the hippocampus, the area of the brain that stores experiences and makes them available for recall. Each time we remember a past event, we are, in a sense, also reliving it and therefore remaking it. Updates or minor revisions to the details of the memory may even occur, to help us make sense of it in the context of our current lives. Although this neuroscience may somewhat demystify the process of experiencing a memory, the bodily jolt of recognition or even identification produced during that process remains ineffable.

Shadows Through a Petal, Emily Margarit Mason’s exhibition of photographs at No Land, triggered in me the same feelings that a strong memory evokes—except I was looking at images I had never seen before. Quite literally, Mason constructs her photographs; each still captures a tableau that she builds outdoors. Found objects such as rocks, plastic tarps, or other photographs of hers layer her compositions. In Backyard Still Life (2017), a wrinkled sheet of silvery mylar is taped to a wall. The wall’s texture and curvature read as adobe, but its inky blackness belies easy recognition. The wildflowers that fringe the bottom edge of the composition are phosphorescent green, white, and electric violet. Likewise, the sky, a band of burnt orange and dark gray, offset by the spindly, white-hot tangle of a tree’s branches, reads as post-apocalyptic, nuclear. In other words, the scene, although recognizable, is not naturalistic. Mason has inverted the digital image to wash out certain colors and to darken others. The shapes are eerily familiar and even instantly legible, but it takes a few seconds to comprehend all that is actually present in the composition. This delay, the time it takes for the brain to piece the scene together is, I think, what instigated a satisfaction identical to finally recalling something that had been elusive, on the tip of my tongue yet just out of reach.

Other photographs are even more complex. Rock Patterns (2018) features a backdrop photograph of a sandstone cliff on which Mason has placed another photograph of mountain peaks and ridges, its corners curling and casting shadows onto the photo below, and weighted down with various rocks (a charming display of some of Mason’s rocks and photographic collage elements appears on the shelves in No Land). The entire photograph is inverted so that the top photograph and rocks flatten into a striated, grayscale pattern, its shadows casting white triangles onto the image below. But the background photograph’s colors show true, meaning that the photograph of that sandstone cliff was printed inverted before Mason placed the other layers on top. This complicated accretion of negative and positive imagery, the puzzled stages of the composition’s development, is most evident in the larger works in the show; their scale has given Mason’s source materials room to expand across the surface of the prints, to cast those almost inexplicable shadows. It also allows some of the site of their making to peek through at the edges, which adds an extra layer of spatial depth. Less exciting for me were Mason’s earlier works, which utilize more traditional collage techniques. Often crowded with cut strips of photographs or other fragmentary shapes, the space within the frame flattens out. The delicate complexity that Mason achieves in her more recent photographs is the result of carefully chosen compositional elements that unfold temporally in the mind of the viewer.